This year we are again proposing our list of the best films although, as our readers are well aware, this publication is not inclined to rate or give stars to films. EL HYPE is not a traffic light that prohibits or vetoes, that allows access with enthusiasm or with reservations, because we prefer to recommend, with respect for the tastes of each person, but using the criteria of those who sign their reviews and evaluate different aspects of the films, not always possible to compare. The year 2022 has been full of audiovisual proposals that have made us enjoy and reflect, that have reinforced our love for moving images, whose quality transcends formats and media. Thus, we include in our list two extraordinary series and an immersive film to which we wish a deserved distribution, making as many viewers as possible happy.

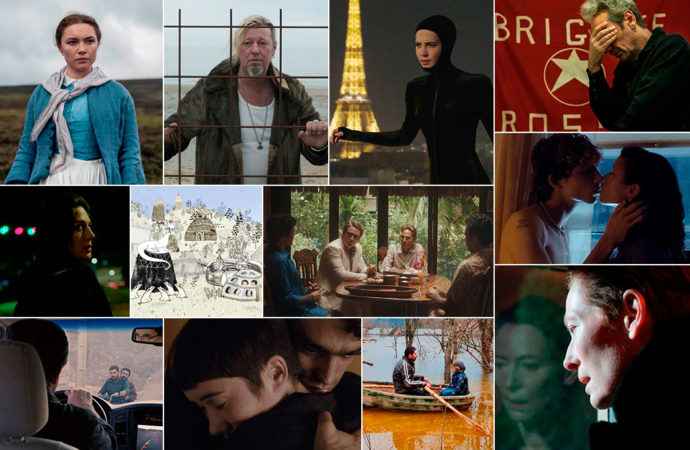

No Bears (Jafar Panahi)

Premiered at the 79th Venice Film Festival in the absence of its director, who is imprisoned in Iran, No Bears (Khers Nist, 2022) is about confinement, a kind of forced confinement that acts on several levels and prevents people from moving, literally and metaphorically, as they please. The metaphor drawn from folklore and intended to forge in children the beliefs of insecurity and the need for protection functions as a conceptual framework, which the director illustrates masterfully, with his characteristic minimalism and also through increasing forcefulness throughout the film. The opening anecdote of No Bears is the stay of a film director, played by Panahi himself, in a small village on Iran’s border with Turkey. From there, from a distance, he is directing a semi-documentary film about a couple of exiles who intend to travel illegally to Europe. Read more.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K5Coj4oibi0

Esterno notte (Marco Bellocchio)

Since his first feature film I pugni in tasca (1962), Italian director Marco Bellocchio has travelled through almost six decades of cinema and Italian history, demonstrating a creative vitality and fruitful maturity that have prevented him from becoming complacent in his formal and ideological achievements. The director revisits a topic already treated in his film Buon giorno, notte (2003), where the spectator contemplated the story of the kidnapping and assassination of Aldo Moro from the subjectivity of one of the terrorists. This time, however, it is through the use of polyphony that we obtain a broader framework for considering the events narrated with such elegance, sense of rhythm, masterful dosage of information – which, while complying with the rules of the serial, is not subjugated to them – and a dazzling mise-en-scène. The miniseries is written by Bellocchio together with great scriptwriters such as Stefano Bises (The New Pope) and Davide Serino (1992 and 1993) and the co-scriptwriter of Il traditore, Ludovica Rampoldi. Read more.

The Eternal Daughter (Joanna Hogg)

The British director, whose diptych The Souvenir (2019) and The Souvenir: Part II (2021) explored in a semi-autobiographical way her beginnings in film and a personal relationship that marked her life, deepens in The Eternal Daughter (2022) the immersion in family intimacy, the memories of another life, that of her mother, and her own feelings about her, in a particular genre film. Hogg’s way of working is a pure open-ended investigation that, in the absence of a millimetric script and corseted dialogue, is finding the final, definitive fit in a collective work with his collaborators. Tilda Swinton has been a necessary accomplice in the making of a cinematic artefact as personal in form as in substance. Hogg’s film moves away from the literalness of memory, because his interest is not in the portrait but in the process and its results. Therefore, he accepts that along the way, new approaches to old memories may appear, transforming the experience and endowing it with an illuminating meaning. Read more.

Bones And All (Luca Guadagnino)

Maren (Taylor Russell) and Lee (Timothée Chalamet) do their best to enter the adult world by breaking rules, creating them when necessary, because their circumstances force them into a literally heartbreaking maturity, and the gaze of the director of Call Me By Your Name is close and empathetic, no matter how bizarre they appear to be. This horror-wrapped romance, whose protagonists are both innocent and monstrous, is as delicate as it is searing, establishing a seemingly irreducible antithesis between poetry and reality, carnage and pure sentiment. In this bloodbath, the motivation and the curse that, in spite of themselves, their protagonists suffer, keeps us in an inner tension as intense as it is uncomfortable, and at the same time subjugating, so well resolved that we cannot but accept it, surrender to it and even feel a no less distressing empathy. Seguir leyendo.

Pacifiction (Albert Serra)

The best film by the director of Liberté (2019) immerses us for three hours in an atmosphere that manages to turn a mysterious and original thriller into a tropical reverie, à la Serra, where suggestion becomes truth and the imagined shapes reality. Pacificton could be an essay on neo-colonialism, the nuclear threat, the melancholy of a decadent way of life that clings to life with the self-absorbed nonchalance of someone who feels secularly installed in a position of privilege, but it is also a hypnotic experience of enormous beauty. The great absentee from the Spanish film awards is one of the best films of 2022, a co-production with France, Germany and Portugal, starring the French actor Benoît Magimel, who plays an extraordinary character, heir and updated, of those diplomats and policemen from the lineage of Claude Rains‘ Louis Renault. His De Roller is a seductive and ambiguous demiurge who gravitates and meanders in a world as real as it is imagined, and whose style completely mimics the tone of the film.

Rimini (Ulrich Seidl)

Forming a diptych with the controversial Sparta, Rimini focuses on Richie Bravo, brother of the protagonist of that film. A melodic singer in his twilight years, who in a stiflingly kitsch universe survives on miserable gigs in third-rate hotels for retired German tourists, which he complements with prostitution or extortion, spends his winter in the Italian city that gives the film its title. Between his senile father, who is reliving Nazism in his final hours, and his rediscovered daughter, who will present him with new challenges and confront his beliefs and prejudices, Richie wanders along the beaches shrouded in winter mist, between beach bars that survive the low season and hotels that are closed, but not to him. Siedl’s always disturbing artistic universe, depicting the lowest forms of behaviour and miseries of a Europe living in a mirage of civilisation, finds a perfect setting for depicting the social decadence of a world with an expiry date.

https://youtu.be/7_wlg1_PsY0

R.M.N. (Cristian Mungiu)

The Romanian director returned to the Cannes Film Festival in 2022 to diagnose his country, but also Europe. In R.M.N. (acronym for nuclear magnetic resonance), set in a rural community in Transylvania, Mungiu expands his object of study to analyse the reality of a world in extinction and the birth of a new order, as if he were investigating a human brain. With the same asepsis with which he films a 17-minute fixed shot and the seemingly balanced distance with which he allows those members of society who represent the forces that hinder the progress of humanity to express themselves, the director offers us an outstanding film. In terms of the pace and dosage of information, the way he weaves the intimate with the political and the relentless portrayal, in well-chosen strokes, of the protagonist Matthias (Marin Grigore), Mungiu maintains his pulse and his impassive fierceness. In the Transylvanian winter, in the middle of Christmas, he transcends the brutalism and immobility of a group, their fear of the foreigner, their problems in fitting more than one culture into a single time and space, questioning the legitimacy of their ancestry, to reflect on a weak and endangered Europe.

Irma Vep (Oliver Assayas)

Actress Mira Harberg, at the peak of her success, travels to Paris to play the most iconic role of silent film baddies, Irma Vep, who was played by the charismatic Musidora in Louis Feuillade‘s film The Vampires. A film within a film, which in turn revisits a real film shooting, Olivier Assayas’ series is a complex study of characters and their transformation as they come into contact with a story and characters that have transcended their time. Alicia Vikander is a graceful, sexy and enigmatic Irma, more than handling the challenge of taking on an updated role that retains its essential character, and she is superbly accompanied by Vincent Macaigne as the neurotic director René Vidal, Jeanne Balibar, Vincent Lacoste and the versatile Lars Eidinger. Irma Vep oozes intelligent humour and is a series where almost no one takes themselves too seriously and has enough courage to distance themselves, sometimes even unfold, and reflect on the creative process and its servitudes.

Holy Spider (Ali Abassi)

Following the success of his fantasy film Border, Iranian director Ali Abbasi directs a crime thriller based on real events, set in his native Iran. Holy Spider, which represents Denmark at the 2023 Oscars, tells the story of a serial killer who strangled sixteen prostitutes in the city of Mashhad between 2000 and 2001. The criminal’s motive stemmed from his fundamentalism, from a messianic and redemptive purpose, from the need to “cleanse” the city of vice and corruption. The creative freedom shown by the director, unusual in Iran, but understandable when we know that he filmed in Jordan, allows us access to the intimacy of women who act as in real life, share a bed with their husbands, are sexually harassed and even, at times, dare to rebel. In Abbasi’s style we recognise a film buff who has been able to interpret and transfer his sources of inspiration from Travis Bickle – exchanging the taxi for the motorbike – to Hitchcock, whom he inevitably reminds us of in prolonged scenes of violence – the struggle between the killer and his last, frustrated victim (Torn Curtain, Dial M for Murder) and in the strangulations (Frenzy).

Manticore (Carlos Vermut)

A pesar de que la pederastia es un asunto importantísimo, estamos ante una película de Carlos Vermut, no lo olvidemos. Esto significa que no vamos a encontrar en Mantícora una aproximación precisamente convencional al tema, que aquí no es ninguna excusa para desarrollar ni una trama policiaca ni un drama alemán de domingo por la tarde. De hecho, el momento en el que la película más se aproxima a una representación gráfica de la pederastia está resuelto con un particular fuera de campo. Lo que de verdad interesa mostrar a Vermut es unos personajes en permanente zozobra emocional, quebrados por el destino, como la Violeta de Diamond Flash o la Bárbara de Magical Girl. O el Julián de Mantícora, seguramente el personaje más arriesgado hasta la fecha en la filmografía de Vermut, por masculino y por el terrible conflicto moral que arrastra. Un personaje que lucha desesperadamente por ignorar, por enterrar, por esconder(se de) su pulsión pedófila. Un personaje que busca en su relación con Diana, más que la curación, la redención de sus pecados: con Diana puede encontrar la paz interior necesaria para mantener a raya ese impulso inconfesable. Seguir leyendo.

Although pederasty is a very important issue, this is a film by Carlos Vermut, let’s not forget. This means that we are not going to find in Mantícora a precisely conventional approach to the subject, which here is no excuse to develop either a police plot or a German Sunday afternoon drama. In fact, the moment in which the film comes closest to a graphic depiction of pederasty is resolved with a particular off-camera approach. What Vermut is really interested in showing are characters in permanent emotional turmoil, broken by fate, like Violeta in Diamond Flash or Bárbara in Magical Girl. Or the Julián of Manticore, surely the most daring character to date in Vermut’s filmography, because of his masculinity and the terrible moral conflict he carries with him. A character who struggles desperately to ignore, to bury, to hide his paedophile impulse. A character who seeks in his relationship with Diana, more than healing, the redemption of his sins: with Diana he can find the inner peace necessary to keep that unconfessable impulse at bay.

The Prodigy (Sebastián Lelio)

The latest film by the Oscar winner with A Fantastic Woman is inspired by the true story of the young women known as the fasting girls, famous between the 15th and 19th centuries for not ingesting any food for months, attracting the attention of curious onlookers and journalists. The legend, and the myth that was built around it through stories of mysticism and magic, is updated in The Prodigy, through an austerely filmed plot involving a Crimean War veteran nurse with a painful family past and an 11-year-old Irish girl who, in 1862, supposedly survives without food in a humble and fervently Catholic household. The film is based on Emma Donoghue‘s novel, where the two opposing poles, scientific and mythical thought, challenge each other in silence, with respect, to arrive at a transformative dialogue, through metaphors – like the bird and the cage painted on two sides of a spinning plate – and an empathy free of prejudice, in a tireless exercise of psychotherapy, reminiscent of The Miracle Worker. Read more.

From The Main Square (Pedro Harres)

This film is the furthest thing from a video game and the most immersive imaginable in this genre of productions, whose dividing line between pure entertainment that explores technical and interactive solutions with more or less brilliance is extraordinarily thin. Redefining the role of the spectator as an active part of the film, whose collaboration is solicited in various ways, and the need imposed by the medium to achieve total surrender to the narrative, From The Main Square, winner at the Venice and Thessaloniki festivals, shows the promising possibilities with which technique can enrich the traditional cinematic experience. Pedro Harres’ film literally places us in the centre of a main square, where we see not only a city but a civilisation grow and transform. The values that represent us, diversity, ideology, philosophy, religion, the conflicts that confront and destroy us are narrated without words, with a special sense of humour and with the only support of music, sounds and onomatopoeias, appealing to our action to amplify an image or trigger an event over the course of 19 minutes. Read more.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!