Tobacco Barns (Secaderos), the first feature film by Rocío Mesa, has arrived at the 64th Thessaloniki International Film Festival in a successful journey that has already taken it to other festivals such as San Sebastian, Seville, Gijón, South by Southwest and Vilnius. The story she has chosen for her feature debut is a daring fusion of realism and imagination, genre and sociology, which is successfully resolved with her own original vision. This was no small challenge, but we have found that the rural tale, which combines the everyday, horizonless life of teenagers with the lyricism of memory, and above all of hope, is as wide-ranging and polyphonic as the personalities of the filmmakers who tackle it.

It is not always a bonus to be considered part of what we could already call a generation of young filmmakers (especially women) who look back to the origins, who are interested in threatened ways of life and the complicated possibility of finding a balance between what the past, the present, and the future have to offer in small communities where the advantages of two different ways of life overlap or come into conflict. However, Rocío Mesa shows that this rural wave is not a pattern but the spirit of an era, a vital restlessness born of the need to explain oneself, to understand, when emotions, affections, what centers us, overflow the labels and force us to find new formulas to integrate and situate ourselves within our skin and history, both personal and collective. Tobacco Barns stars Vera (Vera Centenera), a girl who returns to her grandparents’ village for the holidays, and Nieves (Ada Mar Lupiáñez), a teenager who works as a day laborer in summer, both representing the two sides of a way of life: the paradise of childhood freedom and the growing awareness of the lack of horizons.

We met the director after the screening the night before, and you’d never guess from her enthusiasm and freshness that she has already spent months hearing well-deserved praise and meeting the press in countless meetings and interviews.

EVA PEYDRÓ: After a long absence, you return to Spain from Los Angeles to a small town in Granada, which you chose to capture something that perhaps you had been maturing for a long time because the first film is usually carried inside you for a long time.

ROCÍO MESA: I have lived in the United States for 13 years. I arrived at the end of 2010 with a scholarship, it coincided with the economic crisis in Spain and I stayed until I settled down. But right now I’m transitioning to have my base camp in Spain and, of course, I will continue working with the United States and going there a lot, but I wanted to return. The first films are places where you want to pour out things you’ve been cooking up all your life. In fact, I think that first films, very often, are guilty of dealing with too many subjects because you want to put it all in, but also because you don’t know when you’re going to make a film again. It’s very expensive and you have to have a series of very specific elements, you have to gather the seven dragon balls to be able to make it and you doubt whether you’ll be able to make a second one. There’s a kind of a lively eagerness, a great desire to make that first film. And you tend to see that at festivals of first films, it’s beautiful to see that desire materialize, even if it’s clumsy.

That’s something that I’ve learned very recently and that I think about a lot and that is that I like much more to see imperfect films that have been the result of an attempt to do something, from a real drive of authentic desire, even from a desire to innovate or to do something different, to dare, to be brave, than something absolutely perfect that comes from an intention to please an industry or an audience and that falls back on gimmicks that we’ve seen many times. So I prefer imperfection. This happens a lot in the first films that are imperfect, but there is something very authentic.

E.P.: In your reflection, there is a lot of emotional memory, for example in the rebellion against this limited and predictable life, which Nieves defines as a loop, of which her friends are unaware. You also show it with the proximity of the beach and Sierra Nevada, places to which they have no access, they seem to find themselves in a no man’s land, in a bubble, as in a fantastic story in which an invisible wall prevents them from leaving, not only physically, showing the impotence of several generations to break through it.

R.M.: For me, there was a very clear intention to talk about the duality that we face when we relate to rural areas, how we all fantasize about spending time in an area that brings you peace and connects you with nature. It can be a paradise of relaxation, of communion with your animal side, but it comes with a lack of resources, opportunities, of connection to events that might interest us such as cultural life, because rural life is what it is: economic precariousness, jobs related to the primary sector, which are often very hard physically. But at the same time, we want to be there for the beauty, for the richness of the folklore of the local culture. In this film I wanted to reflect that duality because I grew up in that area, the vega of Granada. I’m from the village and I think it’s a love-hate feeling that has accompanied me all my life.

E.P.: And you express this with two characters who reflect two different attitudes, that of the paradise of childhood and adolescence, a more demanding phase.

R.M.: Absolutely. Because creating these two characters helped me to represent this duality. And I think that in childhood you can see it perfectly because when we are children, we do have that innocence. We still don’t worry about economic problems, the lack of opportunities, about how hard it is to work in the primary sector, the only thing we see is the locus amoenus of nature, with a more fantastic or imaginative explanation. However, adolescence is a time when you are very protesting, very rebellious, and very non-conformist. But I think that these two feelings continue to accompany you as an adult, that is to say, you want the opportunities that the big city offers you, but you want the peace that the rural world gives you. At the same time, with this film, I also wanted to return to my homeland, because in the end, as a creator, you do things that you wouldn’t dare to do in real life and we justify them through art.

So, I, who had been living in the United States for so many years, more than a decade, in a city like Los Angeles, needed an excuse to return to my homeland, to reconnect with it, to recognize it, and to love it. This has been my excuse and my therapy too, in a way. And that’s why I think there’s so much love in the film as well, of course, we talk about the dangers of it because there are a lot of films now that talk about the rural world and romanticize it and create an idyllic rural world. And although I wanted to talk about these dangers of the rural world, I wanted to do it from the most absolute love for my neighbors, for the people who live there, for the people who work the land, for the folklore, for our traditions…

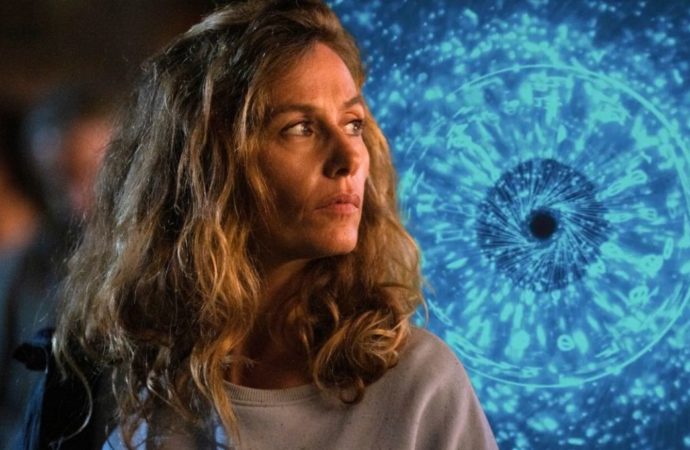

Rocío Mesa at the 64th Thessaloniki Festival. Photo: © El Hype.

E.P.: And you have also used the magical element to express it, in a story as realistic as that of Tobacco Barns. For this you have counted on the presence of this unreal being covered in tobacco leaves like the ones hanging in the drying sheds, created by Montse Ribé and David Martí, Oscar winners with Pan’s Labyrinth.

R.M.: I love magical realism and I find it a very interesting resource. The creature, which we affectionately call the Nico (of nicotine), comes from a real memory of mine, from when I lived in that area and saw the tobacco drying sheds in the middle of the landscape, they are much bigger than the usual dwellings, they are like giant architectural constructions made of poplar wood. In my imagination as a child they were a lair, some are made of brick, but all of them have a kind of aura, a hut, that reminds you of those fantastic stories you have read and that helps you to think of giant creatures.

E.P.: It’s a very Miyazaki character, related to nature and folklore. It also has a revealing role on the characters, because at the beginning only the girl sees it, but I get the feeling that as the characters evolve in one way or another and reach another level of consciousness, they are able to see it.

R.M.: Totally, for me the psychedelic drug was an excuse to open the doors of perception and for you to be able to see other layers of reality. I also liked to think a lot about the origins of that creature, I thought a lot about the workers’ movement that took place in 2002, when the Cetarsa factory (Compañía Española de Tabaco en Rama) was closed, which was the factory that processed the tobacco plant, the epicentre of the tobacco industry in the area. When it closed, there was no longer a justification for growing tobacco there, and hundreds of families were left without their way of life and that was the only thing they knew how to do, because we are talking about people who were born growing tobacco and it was the only thing they knew. The film also has a political message in this critique of the brutal real estate expansion, because I always thought that in this labour movement with so many people protesting en masse, grieving for this wound that has created a paradigm shift and an economic crisis, there is a collective energy that transforms into something.

I thought that all that collective energy of workers and neighbours could become a magical creature, a grieving creature that suffers from the disappearance of the culture of those tobacco barns, that wanders through the disused drying sheds, that wants to protect those people who have worked that tobacco. It wants to be heard and, furthermore, it also wants to fight against this bestial property expansion that is eating up this arable land. This is based on real facts, because in this area of the fertile plain of Granada, precisely after the disappearance of tobacco cultivation, land was reclassified as irrigated land in a dry land area, an irrigated land that has fed us for centuries, that is our wealth. They began to build a type of single-family houses that had nothing to do with the idiosyncrasy of the Andalusian villages.

E.P.: The audience of Secaderos has reacted very positively to this local story because it connects with a more global consciousness.

R.M.: The local is very universal and I think these are problems that are shared in many countries. Not for nothing, at the international premiere, which was at South by Southwest in the United States, we won the audience award in a country that we would never have imagined would connect with such an Andalusian or Spanish story. But of course, all people who have grown up in rural areas, whether it’s tobacco growing or anything else, share those problems.

E.P.: It is inevitable to talk about the connection with the works of other directors who have recently focused on the rural.

R.M.: It has been very nice and very exciting to come across this. You see, because I’ve been living in the United States, I’ve been very disconnected in some ways from the Spanish community, although I run a contemporary film festival there called La Ola, and that has allowed me to be in contact, but I felt that I was making this film in a very isolated way, very alone. However, this film was shot the same summer as other films that talk about the rural world, such as Alcarràs or El agua, Suro or even As Bestas, and it was really nice, when it was released, to find that I had a community. I didn’t know it, I almost didn’t. And then, by sharing festivals and spaces, we have become friends and this union because we have been concerned with very similar themes, such as ecology or lineage, the female voices within the family, the generations of women who live in rural areas and whose voices have not been heard, or, for example, caregiving. Well, all of this has been very nice, to discover that there were colleagues doing similar things and to say: I am not alone.

I have shared this process without knowing it with all these women or with all these filmmakers. And it has seemed very magical to me. I have really enjoyed watching their films and saying that we have almost similar scenes! or characters that dialogue with each other. I give an explanation because, of course, I’ve thought about it so many times and I’ve been asked about it. I was born in 83 and we are all more or less the same age. We have grown up in the analogical world and we are a generation that has lived through the change to digital. Moreover, at very sensitive ages, like in our twenties. And I think that almost without knowing it, it created a bit of trauma for us.

E.P.: We continue with dualities, but you explore syncretism, the possibility of combining the old and the new in harmony, magic, and rational thinking, in a world where there is hardly any room for maneuver…

R.M.: Totally, I think we have done, without realizing it, an exercise of returning to the primary, to the root, to the earth. As we are living in a digital cloud, we have said no, no, no, no, no, let’s go back to where we came from, let’s go back to the origin. And this has also happened in literature. For example, in Spain there is also a generation of women writers now talking a lot about going back to the roots, to the rural, like Irene Solà, and Sara Mesa. In music, we are living in a moment in which all the groups are mixing roots of folklore, flamenco, etc. with electronic music. In other words, I think it’s a generational cultural movement.

E.P.: Music has been a primary interest for you and is central to your life in the U.S. Do you have any music-related projects on the horizon?

R.M.: I’m not working on anything that has to do with music directly, although it is one of my main interests. Now I have many projects open and although music is a major player in all of them, I am currently working on an experimental film that is not a feature film. I practice experimental cinema, in a different way, the cinema of the sensitive versus the cinema of the narrative. I am now working on a film with a girl who is an opera singer, a lyric singer, and there, of course, sound and her voice are very, very important.

Tobacco Barns is available on the Filmin platform.

Header photo© Thessaloniki Film Festival/ Aris Rammos.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!