Teona Strugar Mitevska participates in the MyMetaStories festival, promoted by Unifrance, with the feature film The Happiest Man in the World. The director, born in Skopje, now Macedonia, premiered her film in 2022 in the Horizons section of the Venice Biennale and has also participated in other international festivals such as Haifa, Palm Springs, and Göteborg. The Happiest Man in the World focuses on a still-bleeding subject and seeks to collaborate in the healing of the deep wound of a war between different nations, cultures, and religions, which were once a single country.

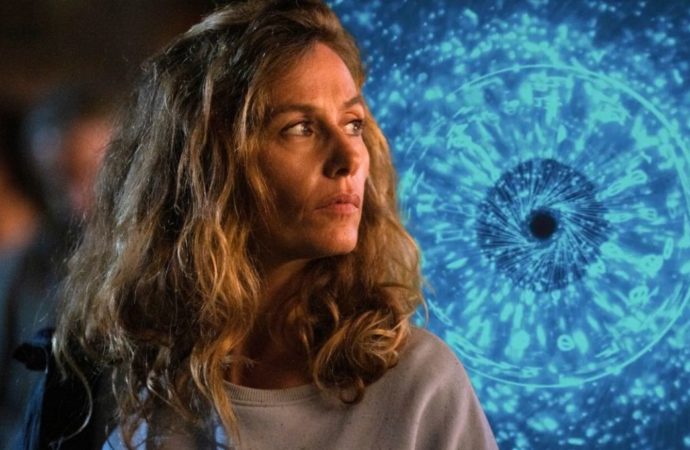

The story of Asja (Jelena Kordic Kuret), a 40-year-old single woman who signs up for a dating event is revealed by her partner, Zoran (Adnan Omerovic), a man of 43, who has come not to seek love but forgiveness from his first victim, whom he had wounded in 1993 during the war in Yugoslavia. Maintaining the three units and the claustrophobic setting of a brutalist hotel reminiscent of bygone eras, the director of the striking God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya performs a successful exercise in dramaturgy, suspense, and analysis, which she discussed with us in an interview.

EL HYPE: First of all, congratulations on your film. It is excellent news that it has been selected for the festival, considering the young audiences it will reach. It is about recent European history, but it has echoes that reach into the present in one way or another. Not only in terms of reconciliation but also in regards of tolerance and coexistence. It is also a very original and powerful way to show the experience of post-war trauma, but based on a true story.

TEONA STRUGAR MITEVSKA: Thank you very much. I appreciate it. Well, the story is of my screenwriter, Elma Tataragic, it is a story she went through. Actually, she lived this. Not exactly as you see it in the film, but, yes, she was shot during the war, during the siege of Sarajevo. And then, after the war, she was a student of dramaturgy and she got accepted into a workshop of dramaturgy, an acting workshop that was organized by the EU and it was about putting the opposite sides together: Bosnians, Serbians, Muslims Bosnians… She’s such a mixture. She’s a Catholic and Jewish and Muslim and everything. It was a sort of workshop that lasted for one week. In one of the sessions where they had to reveal their most deep traumas, a younger man spoke of their experience. Slowly the following days, they actually realized that it was possible that 99 percent he was the one who shot her, and actually the way they recognize the facts it’s as we see in the film: by the blanket, the address, the time, the date.

So, yes, it was a story that she kept with her for a long, long time, and she was trying to find the right form to tell it. Like, how can you speak about war and be constructive, not stay on the grief or self-pity. It was very important for her to actually send another message, and also it was very important for her to speak about Sarajevo today, and what it means to live in Sarajevo. So, we came up with this concept and gave ourselves time, because we went through very strong emotions.

E. H.: And because of the unique place, the three unities, you get the feeling that something must happen for good there. You can’t go out if you don’t resolve that.

T. S. M.: Yes, exactly. That was sort of like a trick dramaturg. Exactly, exactly. In order to deal with the tension. And you know, the truth is that every time you put people in one place and you push them, you lock them, you’re forced to stay together. Of course, everybody can leave when they want, but what happens there is so intriguing that actually, she cannot not stay. Her curiosity gets a reason and she really needs to know. So it becomes this quest of truth and, you know, finding peace and forgiveness and anger.

E. H.: And you gradually show all the steps, the descent to the bottom, with each of the reactions that occur.

T. S. M.: Yes, and this is something that is based on Elma’s personal story, but also on a lot of research, you know, writing the script, we actually had to really dive into the problem, in order to be the most truthful possible. It was the story of two of them. And then, as we did the research and, for six months, we were just traveling around Bosnia and gathering experiences, then we did the casting and we started working with a whole group of people. And as we started diving into the material and into the experiences of the actors themselves, we discovered how important are the stories of the side cast, because they can expand. Explain better the context. These two main characters find themselves in it.

E.H.: Maybe it was a double experience, it was group therapy at the same time.

T.S.M.: Absolutely. Absolutely. And then what happened? The private, personal stories of the cast themselves, became part of the story, so we integrated also that into the script. So really, it was a group effort, you know, it was a true collaboration. We can talk about really, truly, a collaborative process working on this script. It was also therapy for all of us, a learning experience, a learning curve. The thing is really, of course, it’s about love, but for me, it’s really about understanding the other. There is a big message behind this for us. I’m Macedonian. So I did not go through the war, but I did. I’m part of the generation that is a victim of the end of Yugoslavia, you know, the end of Yugoslavia affected us all profoundly. It really traced our trajectory, who we became, and who we are today. So we also wanted to send a message about, you know, this openness and talking to one another.

What has happened 30 years later after the war, we hardly speak to one another. I’m not saying everyday talk, of course. Each fraction, each republic, each country right now, not a republic, has its own interpretation of what happened, especially Serbia versus Bosnia. And this is horrible. That means like, if you can agree on facts, how can you actually build any kind of future? How can you evolve?

E.H.: And there’s also a problem with the different generations. Because the young ones don’t want to hear about the stories of the war. They prefer to forget or build a wall between them and the past. And it’s terrible, you show it also in your film.

T.S.M.: Exactly. This is also a concern of ours, a deep concern, and this is why there is that scene at the end of the dance, which is liberation, but also it shows this contrast between this generational divide.

E.H. In your film, black humor works as a means of taking distance from the conflict and seeing it in a different way and it’s very effective.

T.S.M.: That’s the way I work with Elma, you know, she does the structure. And me, I do the dialogue and I love this is something that is installed in our culture, this dark humor. It is something we grew up with. It is about thinking intelligently and also looking at the back of things and between sentences, between words, and doing little subtle punches. So it’s almost like music to me. If we talk about technically, it is such an effective tool to think about difficult themes. It’s useful to reflect and at the same time to take a distance. Absolutely. You need to reflect. If you know how to do it well, it can actually do wonders.

E.H.: The film gives the impression that it could have been a play, was this format thought of at some point?

T.S.M.: It was always a film because I actually never worked in theater. But, last year, a few people reacted like you, so I have been negotiating with a theater troupe to do a play. But then I said, okay, maybe I will do it in two years because I have too many projects. But actually, the way we prepare the film, I could actually take the crew and actually put on the theater play. So it is something that should be, must be put in theater. And actually, we would love to give the right to somebody. There’s just, there’s not enough hours in the day.

E.H.: Tell us about the location, the brutalist building where the action takes place. Is the Holiday Inn for real?

T.S.M.: No, it isn’t, we couldn’t shoot in Sarajevo in the Holiday Inn. Because it’s a co-production with Macedonia, we had to shoot in Macedonia. So, this building that you see actually is the University library in Skopje, transformed into a hotel for the needs of our film. However, we are not very far from the truth, the Holiday Inn was built in the eighties, but we have in Yugoslavia such a big tradition of brutalist architecture, that it’s something that we all recognize and actually it’s part of our cultural heritage. You can do any location, but in order to enrich the story and the experience you’re delivering for the audience, the place is extremely, extremely important. So most of the film is in the University library and then all the hallways, and the bathrooms are shot in the University of Skopje, which is also this amazing architectural creation, and in some way very cold, very overwhelming. At the same time, at the core, are the emotions, are the feelings.

E.H.: How was the casting process?

T.S.M.: Well, for me, it was very important, as we started doing the casting, we understood that, of course, it’s a story of the two, of Zoran and Asja, but actually the rest of the cast is extremely important. So we were actually casting for a troupe. Of course, we started with two of them, and then there was the troupe. We found first Zoran and then he did rehearsals with everybody in Bosnia. And then, I remember, during the scene the first day, when Yelena came, to rehearse the scene of Asja, and they were trying the scenes, and me and Elma, we were looking. And at one moment when we looked at one another, it was like, what is this? It feels so real. It feels like they’re not even actors. It feels as if we are in some cafe and we are hidden and looking at two people communicating. At that moment we knew this was it, you know.

E.H.: There is a gradual attraction in the first moments, like a flirtation, which is somehow kept going, it is an ambivalent relationship. Little by little, it gets warmer and nicer, and it changes again, and it’s amazing because you are watching how the feelings change all the time.

T.S.M.: It’s not easy, but it’s essential, things are not black and white. There is always this absolutely between, and this is what I’m most interested in, but, you know, bad casting and good casting can make or destroy a film and it is like me when I do casting, I just don’t stop. I can be relentless in my search for the right person until I find the right person, I actually cannot project myself making the film.

E.H.: The images of the film shot indoors are beautiful and very expressive, what artistic references did you take?

T.S.M.: Did I have artistic references? Probably I did. I can’t even remember. Let me think. I will tell you about my process better. For me, it was very important to make a monochrome film. That was the challenge. The background is brown, and this is why we chose the pink blouse they are putting on because they resembled the background. They fitted the background perfectly because I understood that this is a film of faces, of characters, and that everything else needs to sort of blend in. Also, it’s the first film that I have done where the camera is moving. I come from a painting background. Have you seen God Exists, Her Name Is Petrunya? So, you know, there, everything, every frame is still, and every frame could be a painting, a picture, so there is a big research into colors and a certain harmony and balance and disbalance. This is the first film where the camera is moving, where I actually cannot control the framing, which is something that I actually feel very comfortable with. So it was a challenge to allow myself to go there. But then I said, okay, this is a film that actually is about the characters, the emotions of the characters, and also it is about the emergency, urgency of the moment, how to capture the truth of the moment. So basically, really, my artistic research into this film was that each scene that you see could have not happened two seconds before or two seconds later. Exactly. Exactly.

E.H.: And what are your next projects?

T.S.M.: I’m actually preparing a film. I’m in pre-production, I will shoot most of it in Belgium because we shoot inside in the studio, and then I will shoot for one week in Calcutta. It is a historical film that happens in 1947 in Calcutta, India. We follow a woman for seven days of her life, a historical figure. But it’s again a small film in terms of, you know: a woman, three characters in a closed space, showing this other side of history, like pushing the boundaries of a successful woman back in history, how we interpret them and what is her ambition. As women, we are always sort of imprisoned by certain expectations.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!