On September 16, 1977, Maria Callas, one of the greatest singers in the history of opera and undoubtedly the most important of the 20th century, died of a heart attack at her home in Paris. The image of her body lying on the floor, covered by a white sheet, surrounded by policemen, her two servants and nurses, is the scene that opens Pablo Larraín‘s latest film, which officially opened the competition section of Venice 81. Maria, the film’s title, completes a trilogy dedicated to great female figures of the 20th century, which began with Jackie and Spencer, also presented at Venice in 2016 and 2021, respectively.

This third installment, we can say it right away, is undoubtedly the most successful of the three, as it perfectly integrates the performance of the main actress with the central idea that governs the script, written by Steven Knight. The plot focuses on the last week of life of the great singer, who lives an isolated existence in a luxurious apartment in the center of Paris, accompanied only by her two faithful Italian servants, Ferruccio and Bruna.

Tormented by not being able to continue singing after having left the stage four years earlier, due to health issues and her dependence on medication that had left her without voice, she lives her days trapped between a ruthless reality and the fantasy of starring in a documentary interview about her career and, above all, her private life. This approach allows Knight to tell a story in which reality and anguish intertwine, and which Larraín, with his characteristic imaginative touch, manages to pull off without falling too far into the somewhat surreal excesses of his previous films.

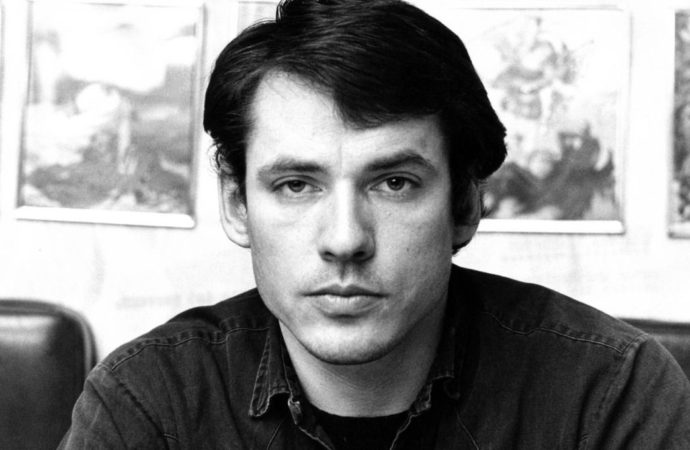

Angelina Jolie as Maria Callas in Maria by Pablo Larraín.

On the one hand, the servants, splendidly played by Alba Rohrwacher and Pierfrancesco Favino, try to be an anchor to reality and a brake on the singer’s evident self-destruction. On the other hand, the memory of the intense life of a great artist, acclaimed worldwide, seems to be the only form of recognition for a woman who has lost the meaning of her existence. Whether or not this is the reality in which the real Maria Callas lived in her last years, after she stopped singing (no doubt tormented, from what we know of her), is not what is most relevant to the value of the film. It actually manages to effectively capture the soul of a character who lives her past as something that has shaped her being as a woman and an artist, but which has also been the cause of an inner torment without a possible solution.

Contributing to this tragic portrayal is the performance offered by Angelina Jolie, faced with a very difficult task, since the charisma, both in life and on stage, and the joyful melancholy that characterized Maria Callas’ face are practically impossible to recreate, as can be seen in the last original archival images of the singer, shown at the end of the film. Jolie nevertheless accomplishes her task very well by avoiding a simple imitation of the original character, working masterfully above all on the most intimate feelings of a human being, Callas facing the impossibility of managing a loneliness and a past that comfort and torment her at the same time.

Angelina Jolie as Maria Callas in Maria de Pablo Larraín.

The episodes of Callas’ personal and artistic life, selected by Larraín and Knight, follow a very narrow emotional framework, such as her relationship with Aristotle Onassis (Haluk Bilginer) or her sister Yakinthi Callas (Valeria Golino), leaving aside other fundamental figures in her life (such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, who was a great platonic love of the singer) and, above all, her importance not only as a singer, but as a great interpreter of the Italian opera repertoire of the 19th century and as a musician. These aspects would undoubtedly have further enriched the Chilean director’s work, but they do not detract from an intense and captivating feature film throughout.

Úrsula Corberó and Nahuel Pérez Fanego in The Jockey.

Less intriguing, although interesting for its visual approach, was the eighth feature film by Argentine Luis Ortega, who arrives at the Venetian competition with a film of an evident surrealist cut, although he does not always achieve the strength that this style requires. The Jockey follows the adventures of an eccentric and nihilistic race jockey, Remo Manfredini, masterfully played by Nahuel Pérez Biscayart. Alongside him is Abril (Úrsula Corberó, known for her participation in the series La Casa de papel), also a jockey, who is expecting her first child, but is torn between carrying the pregnancy to term or continuing in the world of racing. On the day when both could free themselves from their debts to the criminal world of gambling, Remo suffers an accident that starts his wandering through the streets of Buenos Aires, with markedly dreamlike features, in an attempt to find a meaning to his life and his destiny.

Úrsula Corberó and Nahuel Pérez Biscayart in The Jockey.

The film is characterized by a visual approach marked by the insistence on shots that are constantly projected in search of what is outside each frame, an obvious way to emphasize the character’s quest. The approach is undoubtedly original, as well as some surrealistic solutions that add an amusing touch to certain characters. However, as the minutes progress, the plot and symbolism become increasingly cryptic, which makes the film lose interest, leaving the viewer increasingly disoriented.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!