When Luigi Nono‘s Prometeo was premiered in September 1984 in the Church of San Lorenzo, it was an event for the city of Venice. I was only 16 years old and I vividly remember the enthusiasm, as well as the controversies —which always accompany the premiere of something very new and groundbreaking— in the cultural environments of a culturally vital city that had not yet become the tourist amusement park it is today. “The music I am looking for is written with space: it is never the same in any space, but works with it,” Nono wrote in 1983, in the midst of the gestation phase of Prometeo, destined for the 1984 Music Biennale, then directed by Carlo Fontana.

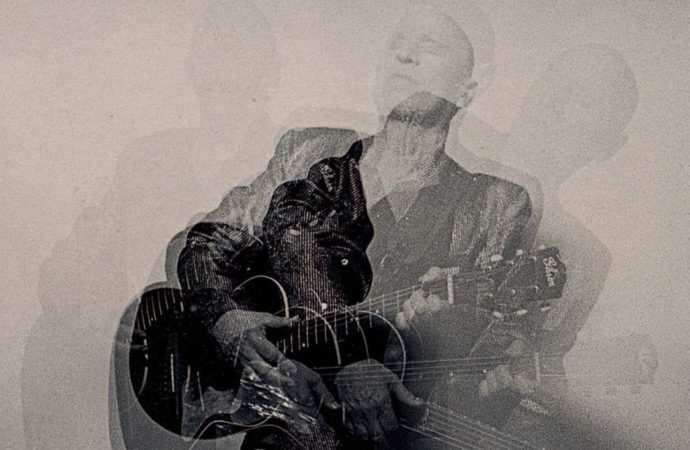

Luigi Nono during the preparation of Prometeo. © Gianni Berengo Gardin – Contrasto.

The historic venture was the result of a collective effort that involved some of the composer’s historical friends, starting with the conductor Claudio Abbado, the philosopher Massimo Cacciari, writer of the text, and the painter Emilio Vedova, who imagined a particular lighting design to paint that space that with the music was presented as a unique object. The architect Renzo Piano also created a very peculiar installation: an ark raised from the ground that brought together musicians and spectators, conceived with the characteristics of a real gigantic musical instrument.

A moment of Prometeo‘s rehearsals in 1984.

That ark wanted to be the space of a new conception of “drama in music”, elevator of an absolute dramatic vision, where the protagonist was the listener. Thus was born a new and singular genre, a “tragedy of listening” as Nono called it, the summit of his aesthetic vision that, despite his communist militancy, brought in his works the desire to reach a form of transcendence that included the experience of the audience itself.

A moment during the execution of Prometeo in 2024. © Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

Also for today’s spectator of Prometeo, although it would be better to say the listener, the suggestive invitation to open oneself to a multiplicity of sound paths that this work offers in its infinite and indefinable dramaturgy, made of fragments, phrases or words barely whispered and dissolved in the continuous flow of sounds, remains unchanged. The texts in Greek, Italian and German assembled by Massimo Cacciari, also resorting to Walter Benjamin‘s writings, are part of the intrinsically musical nature of a work that does not want to tell a story, but the utopian aspect of the myth of Prometheus taken to new sound horizons, well anchored by Nono to the acoustic experiences of the Venetian musical Renaissance.

A moment during the execution of Prometeo in 2024. © Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

Forty years later, at the end of January, the Church of San Lorenzo once again hosted Nono’s work on the occasion of the centenary of the Venetian composer’s birth. The initiative was once again taken by the Venice Biennale, specifically by the Historical Archive of Contemporary Arts, as part of an agreement with the Luigi Nono Archive Foundation for the transfer of documents and materials to the Biennale’s nascent International Research Center for Contemporary Arts. Despite the absence of the giants of the time, the execution was exemplary throughout. Renzo Piano’s ark, now impossible to recuperate, gave way to a circular structure that embraced the two sections of the church. The 79 performers were distributed on various levels, even overlapping, around and above the audience divided into four enclosures in the two sections, according to the direction of Antonello Pocetti and Antonino Viola and the lighting design by Tommaso Zappon.

A moment during the execution of Prometeo in 2024. © Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

The new proposal found a solid guide in the concentrated gesture of Marco Angius, assisted on the “podium” by Filippo Perocco to overcome the not few obstacles that the peculiar architecture of San Lorenzo imposes on the execution of a score in which every gesture and breath is meticulously indicated by Luigi Nono. Distributed on the high scaffolding were the musicians of the Orchestra of Padua and Veneto, assisted by exceptional soloists, such as flutist Roberto Fabbriciani and tubist Giancarlo Schiaffini, already present forty years ago, as well as clarinetist Roberta Gottardi, violist Carlo Lazzari, cellist Michele Marco Rossi and double bassist Emiliano Amadori. The homogeneity obtained by the vocal section, justly devoid of any protagonism with the sopranos Rosaria Angotti and Livia Rado, the mezzo-sopranos Chiara Osella and Katarzyna Otczyk and the tenor Marco Rencinai together with the Friuli Venezia Giulia Choir, also stood out.

To these were added the recitative voices, often reduced to a whisper and phonemes, of Sofia Pozdniakova and Jacopo Giacomoni. Not forgetting finally the fundamental live electronic sound direction, present in the score, wisely entrusted to a historical collaborator of Luigi Nono, Alvise Vidolin, together with Nicola Bernardini and Luca Richelli and realized by the Center for Computational Sonology – DEI of the University of Padua.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!