Since March 2020, the ravages of COVID have affected cultural events of all kinds, including the Cannes Film Festival, which waited almost until the last moment to give up. The cancellation of the world’s most famous event was one of the most striking because of its repercussions both among professionals and because of the popular expectation of its red carpet, its inevitable and now traditional controversies – remember the supposed obligation to wear high heels at the gala sessions – and the economic consequences for the city and all stakeholders.

The 74th edition, which kicks off on 6 July, on unusual dates and in sweltering temperatures, far from the spring temperatures we are used to, will run until the 17th. Among impressive security and hygiene measures, in addition to the metal detectors and the Vigipirate programme that has been in place for years, accredited journalists must show their vaccination certificate when entering the venues, or, failing that, undergo saliva tests every two days. Also, tickets are booked online to avoid queues and, inevitably, the number of accredited professionals covering the festival has decreased. It remains to be seen whether the new sanitary conditions will also affect the parties and receptions that the organisers, producers and moguls are used to hosting, which are also a powerful attraction for industry and business.

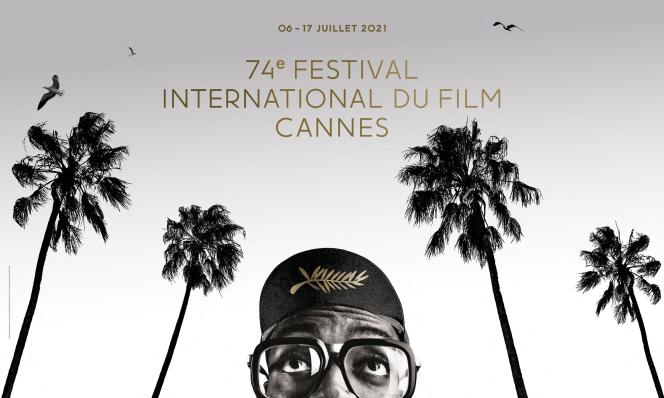

The festival will have an Official Selection Jury chaired by Spike Lee – who also stars in the festival poster, flanked by Californian palm trees in evocative black and white – and made up of actresses Mélanie Laurent, Mylène Farmer and Maggie Gyllenhaal, actors Tahar Rahim and Kang Ho Song, directors Mati Diop and Jessica Hausner and director Kleber Mendonça Filho.

On 3 July, Pierre Lescure and Thierry Frémaux presented the Official Selection programme, which kicks off with a powerful opening film, Leos Carax’s Annette, a unique musical starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard, the preview of which has raised the usual expectations of other editions. The selection, in addition to the opening film, includes the following films: The Story of My Wife (Ildiko Enyedi), Benedetta (Paul Verhoeven), Bergman Island (Mia Hasen-LØve), Drive My Car (Ryusuke Hamaguchi), Flag Day (Sean Penn), Ahed’s Knee (Navad Lapid), Casablanca Beats (Nabil Ayouch) Compartiment no.6 (Juho Kuosmanen), The Worst Person in The World (Joaquim Trier), The Divide (Catherine Corsini), The Restless (Joaquim Lafosse), Paris 13th District (Jacques Audiard), Lingui (Mahamat-Saleh Haroun), France (Brunom Dumont), La Fracture (Catherine Corsini) The Worst Person in The World (Joaquim Trier), Memoria (Apitchapong Weerasethakul), Petrov’s Flu (Kirill Serebrennikov), Red Rocket (Sean Baker), Nitram (Justin Kurzel) The French Dispatch (Wes Anderson), Tre Piani (Nanni Moretti), Titane (Julia Ducournau), Tout s’est bien passé (François Ozon), A Hero (Asghar Farhadi).

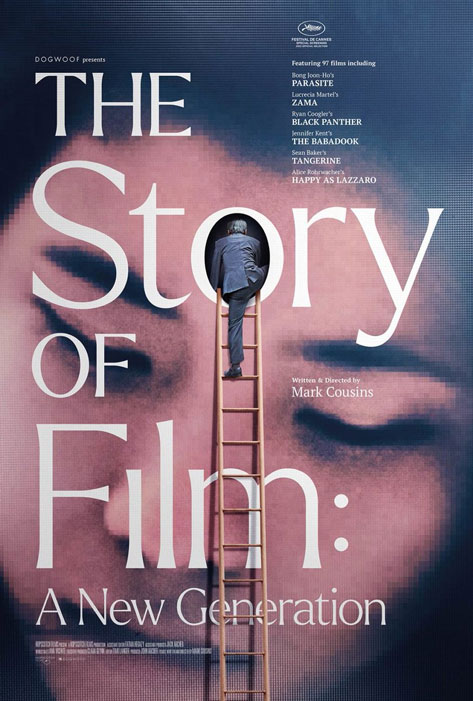

The festival kicked off with Mark Cousins’ documentary The Story of Film: A New Generation, a delightful tribute by the charismatic cinephile, director of Women Make Film (2018), which couldn’t have been a better choice after the cinematic void we have suffered. Pushing the boundaries of cinema is what the films selected by the Irish director have in common and which mark the paths of the seventh art in the last millennium. And that is exactly what characterises the entire filmography of Leos Carax, whose latest film, long awaited, has become immediately controversial.

The director of Holy Motors (2012) adapts the operetta Annette composed by Ron and Russell Mael (the duo Sparks), conceived for a concert tour, and has turned it into a film, once again challenging the viewer to the extreme to which we are accustomed. Annette’s story is one of corrupted love, of innocence and twisted intentions, but also of the abysmal temptation to succumb to fame, professional ambition, even if along the way jealousy, resentment and raw emotions drag you down in an endless fall.

Carax does not make it easy for the spectator and resorts to various distancing mechanisms that put our capacity for fascination to the test. From the opening sequence in which the director himself, the composers and the protagonists appear, preparing to embody their characters, in a sequence shot in the Hollywood tradition, to the dehumanised representation of Annette, the daughter of the protagonists, the resources distance us from realism. The transitions and the sets show us that the story we are watching is just that, a story in which, in the style of Lola Montes, the protagonists reinterpret themselves to expose their lives to the morbidity and scrutiny of the fans.

The musical vehicle that turns Annette into an opera that replicates the dramas played by the lyric singer Anne (Marion Cotillard), transformed into the woman who dies every night, real or figurative, offers a lavantised Adam Driver (the comedian Henry McHenry) the opportunity to raise his acting register to the stratosphere. In a trance of more than two hours, the actor travels a high-voltage emotional journey, in which there are no forbidden or unexplorable territories, in what is, by all accounts, a gift from the gods for someone who is the flag and hallmark of particularity, in interpretative style and physicality. We can say that Driver is more Driver than ever in this role, to which he brings a depth that we do not appreciate in Denis Lavant, who on the other hand does not need much effort to be awe-inspiring.

Israeli director Nadav Lapid has presented Ahed’s Knee, in which Nur Fibak and Avshalom Pollak give a highly intense performance. The story, which borders on autofiction, situates a film director in a tiny village in the middle of the desert, where he goes to present one of his films, while exorcising the individual and collective rejection and guilt of a nation that lives self-absorbed and with its back to the world, symbolized by the aridity of a landscape that takes on great prominence.

The director of Synonyms (2019) draws on the true story of Ahed Tamimi, the young Palestinian girl who slapped an Israeli soldier, to immerse himself in an exploration of grief. In the tradition of films that reflect on the work of filmmaking, Lapid burdens his protagonist with the additional burden of the impending loss of her mother, who was her screenwriter and collaborator. Ahed’s Knee is a brave and angry film, which perhaps over-emphasises too much.

François Ozon‘s Tout s’est bien passé offers an unoriginal perspective on euthanasia, but with the charm and clarity of the director of Dans la maison (2012), who adapted Emmanuèle Bernheim‘s novel of the same title. Sophie Marceau plays the daughter of an elderly man who wishes to die after suffering a vascular accident, played by an award-winning André Dussollier. The film flows with elegance and efficiency, with Hanna Schygulla and Charlotte Rampling contributing, and depicts step by step the vicissitudes involved in assisted suicide in a country where it is still a crime.

In his usual style, Ozon approaches social issues from the point of view of the individual, and in this case he also does so with his characteristic black humour, which manages to disarm the deepest of debates.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!