Yellowstone is the neo-western series that has been breaking US television ratings records and diversifying critics over the last few years, especially in terms of target and political interpretation. The series has quietly arrived in Spain recently on the new Skyshowtime platform, as have its recent period prequels 1883 and 1923, the latter starring Harrison Ford.

The quintessential American genre never dies. It is more resilient than the cowboy of just causes when he is shot at. The hero who deserves to be spared from the grim reaper endures as many bullets as it takes. Though he may seem to be dying, there is no quarrelsome villain under the sun who has managed to hit him in the heart.

Behind the Yellowstone phenomenon are co-creators John Linson and Taylor Sheridan, the latter also at the helm of the series’ script and director of several episodes. Sheridan is the screenwriter of the social western Hell or High Water (nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay and nominated for the Un Certain Regard award at Cannes), Sicario (directed by Denis Villeneuve and nominated for the Palme d’Or) and Wind River (directed by Sheridan and winner of the Un Certain Regard award for best director).

Set in the state of Montana, Yellowstone is a hybrid of topical television drama and American western myth. Audiences, especially in the American South and Midwest, have embraced it with a thirst for westerns. Its ingredients include nostalgia for the cowboy life, family conflict, corruption in local politics, fistfights, deaths galore, stoned conversations and protagonists who are addicted to taking the law into their own hands.

Aerial photography of Yellowstone captures the tensions between rural tradition, activist and conservative environmentalism, the interests of the state, the voracity of capital, and the role of Native Americans in this intricate web. In Yellowstone almost everyone is an anti-hero, but some are principled.

At the epicentre of these frictions of interest is the Duttons’ Grand Ranch, a cattle ranching empire with a century of family history. There the workers, men and women, have a vassal-like bond of belonging and loyalty to the ranch. It encompasses a vast expanse of semi-pristine land in the state of Montana bordering Yellowstone National Park and Paradise Valley. A paradise of meadows, mountains and beautiful sunsets. The ranch is large enough to rent a helicopter when you don’t have all day to go horseback riding.

The remnants of old-world ranching authenticity are under siege by voracious progress. When they don’t want to build a high-end casino nearby, they want to build a large development of second homes for city slickers to wear cowboy hats on holiday, and if not, the state tries to expropriate the land to build an airport and a ski resort to create thousands of jobs.

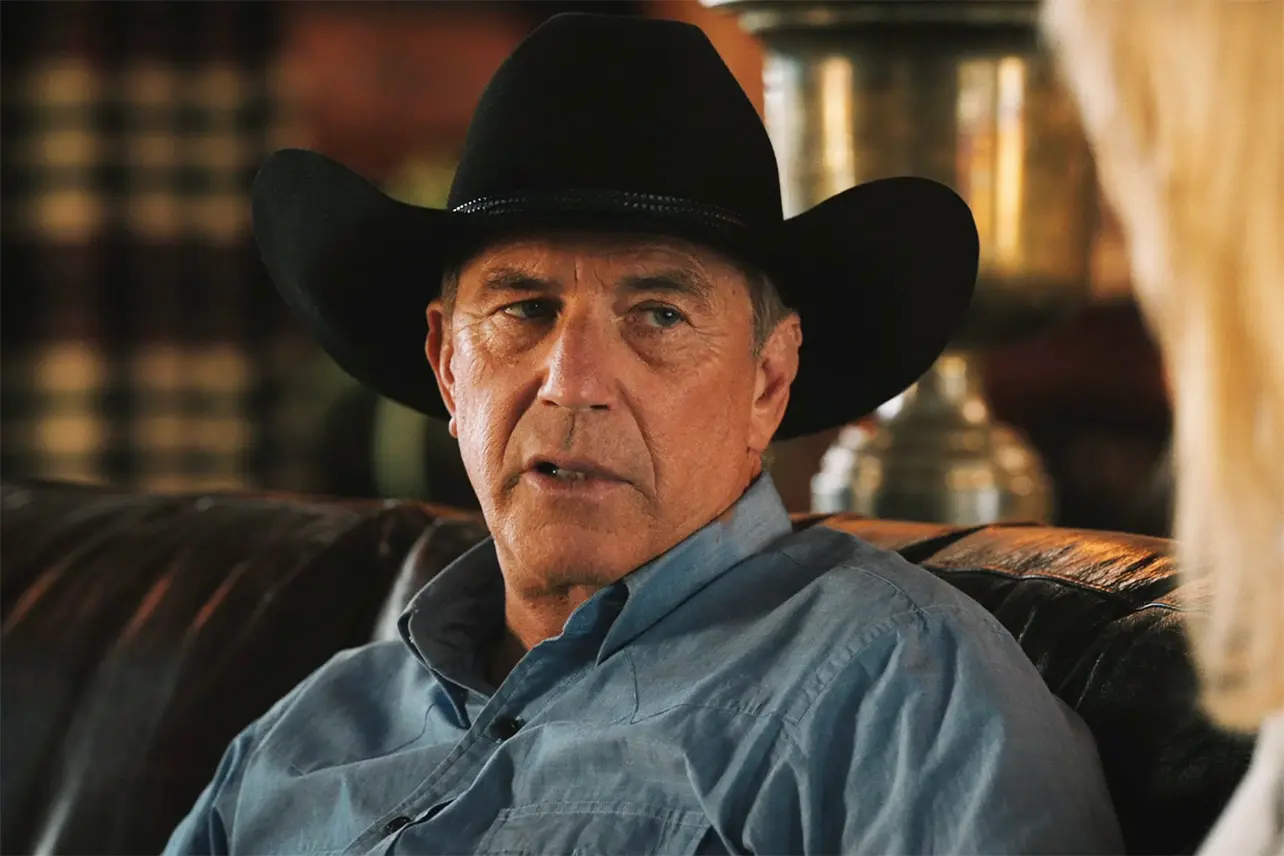

It is the merciless epic of a clan against urban sprawl, in defence of a way of life and the legacy of generations. At the head of the family, played by Kevin Costner, is the widowed patriarch: John Dutton, a stoic man of his word, rough on the outside like the bark of an oak tree, implacable, good in good times and bad, even better.

Costner, whose performance was recently recognised with a Golden Globe, radiates a charisma and solidity that make his role the cornerstone around which all the other characters orbit. His three children, a lawyer with political ambitions, a lethal financial expert and a military man with a very good aim, are the extensions of his struggle against the encroachment of modernity that plagues his ranch and that of other small ranchers.

La hija, Beth (Kelly Reilly), que hace gala de un empoderamiento femenino enriquecido con anabolizantes, un complejo de Electra sin complejos, labia cáustica y un aguante prodigioso para la bebida, protagoniza algunos los duelos más cruentos de la serie perpetrados con la palabra (y no sólo). En otro lado, están los intereses de los indios adscritos a una reserva ficticia colindante llamada Broken Rock, cuyo presidente interpreta Gil Birmingham, que ya trabajó con Sheridan en Comanchería junto a Jeff Bridges.

The daughter, Beth (Kelly Reilly), who displays anabolic-enriched female empowerment, an unabashed Electra complex, a caustic tongue and a prodigious stamina for drink, stars in some of the show’s most vicious verbal duels (and not only). Elsewhere, there are the interests of the Indians attached to an adjoining fictional reservation called Broken Rock, whose president is played by Gil Birmingham, who previously worked with Sheridan in Hell or High Water alongside Jeff Bridges.

At times, the credibility of some secondary characters is uneven, just as some subplots fizzle out into themselves without saying goodbye. Notably, there are no subjugated or disrespected women in the present of the series. Jealousy issues, if at all, are resolved man to man. To find male violence you have to travel back in time with a flashback to the past. Now they are all free women, emancipated and masters of their lives. Some of them are also capable of using the tools of politics and economics with the worst aggression.

However, the portrayal of the more family-oriented Native American, who, having one foot on each side, could be a very interesting character, is incomprehensibly insubstantial. Every character who gets beaten up in this series ends up dishevelled but in one piece. Whereas she, when she mistakenly intercepts a punch that wasn’t even intended for her, gets a stint in the hospital plus rehab. Even with its inconsistencies and imperfections, the fabric of the plot moves steadily towards the inexorable war between the old world and the new.

It is clear that there is an enjoyment in parodying —and even humiliating— the urbanite. Be it the sophisticate, the snob or the city ecologist. Especially the coastal Californian who comes to tell them how to do things without understanding or sharing their values; to appropriate their landscapes and exploit their folklore. Apart from the fact that they don’t even have a half a slap on the wrist, as they make clear on several occasions.

The entry into the vegan arena is, in context, a losing one. There’s a special sense of glee in the double duel between Beth Dutton and a vegan girl who, through the vicissitudes of life and the courage of the script, is forced to become part of the family sphere. It’s not nice to spoil one of the most sought-after scenes of the series on the Internet, but you should know that if you don’t like the menu, in Montana they also serve salad of blows. The situation becomes so fierce and crazy that the only thing left to do is to take it with humour and run away from it. And the screenwriters had their drinks held several times. It must also be said that, after the storm, the initial attempt to build bridges so that both sides would come to a better understanding of the other’s position is put back on track.

One of the most interesting things about Yellowstone’s discourse is its ability to confound critics who want to place it on either the Republican or Democratic side. Another thing is the audience it has managed to win over. Even in its ambivalence, its content clearly points towards a severe critique of gentrification, resource grabbing and the opportunism of public institutions. It is also a continual reminder of the territorial predation, genocide and harassment of the natives on which the US nation is built.

On the other hand, the ethical filter of its attractive characters seems more like a sieve with holes tailored to their personal interests. Sheridan himself has strongly denied that this is a discourse aligned with the red party. But why does this series appeal to people in more conservative areas?

Perhaps this success in the more traditionalist sectors responds to the demand for a conservative romanticism on the part of a public that misses seeing its way of life reflected on television, its folklore, its values, and probably also misses a certain political incorrectness on certain issues. And they probably also miss a certain political incorrectness on certain issues. Is it possible that this enchantment does not make them see the harsh structural critique behind it? Even if it were serendipity, is it possible that a film, like a holographic image containing two sides, can say one thing and the opposite depending on the angle from which it is viewed? If so, we are coming to the perfection of the concept “for all audiences”.

One of the phrases that can be read most often on the merchandising products of the series is My land, my rules. With this alone, we would have a melting pot of interpretations, implications and applications.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!