Reading Uwe Johnson takes us back to the dawn of the construction of the Berlin Wall, in Two Views (Zwei Ansichten, 1965) he narrates the experience of the Cold War from the heart of Germany. The Wall is that “disease” which, according to Max Frisch, Johnson described earlier and better than any of his generational colleagues (no one had written about German division before). With the global advance of authoritarianism, it is more necessary than ever to read it today.

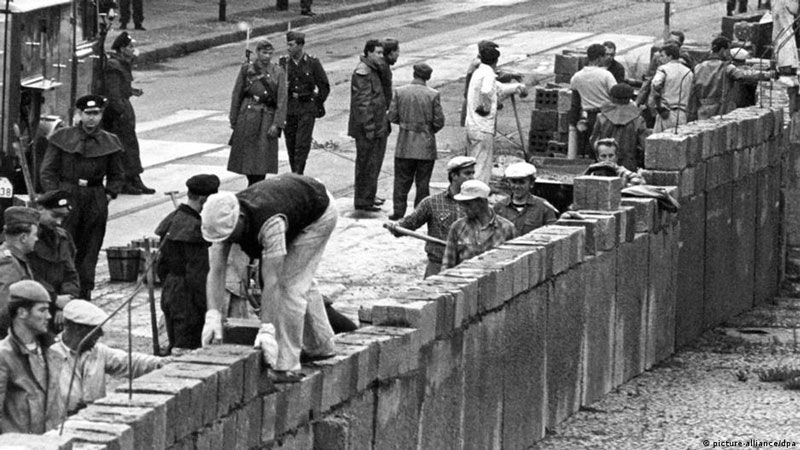

Summer 1961. A couple in their twenties are torn between giving solid form to a vague idyll or sinking the experience into oblivion. It is August and barbed wire has sprouted one night, splitting the city as Berliners sleep: she is Eastern and he is Western, will they be able to see each other again?

Johnson, who never managed to align himself with dogmatic Marxism or the iron Soviet bureaucracy, knew first-hand what the loss of freedom meant. His inability to find work made him leave his native Pomerania for West Germany, where he published this novel in 1965. His novels would be a great success in both territories and would express his people’s need to define a new national mood. With Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Heinrich Böll, Günter Grass, and Paul Celan, he was to form part of a nucleus of generational writers who called themselves Gruppe 47. Artists who took up the zero point of German art after the war concocted a response to the mythical question posed by Adorno: can one write poetry after Auschwitz?

Uwe Johnson (1953).

Two Views is not conceived as a political novel, but as an anti-novel, and the author avoids mentioning the names, institutions, and even the acronym of each new German country; for 258 pages, the only thing that places the reader on either side of the Wall is the word “Eastern” or “Western”. Despite this, Johnson would be remembered as the writer “of the German divide”, given his penchant for portraying with detail the points of union and disunity of the two idiosyncracies. The different, even opposing, ways in which the government falsifies reality. Nevertheless, his characters suffer on every page the weight of their political model at the core of their routines: she being expelled from university or her flat, he blinded by acquiring more and more ostentatious cars.

The story is a cumulative succession of descriptive details, of things that surround the protagonists, and seems reluctant to use direct dialogue and full stops. There is a narrative density that, at times, becomes too oppressive. But the style is so captivating that it holds the novel together. Johnson moves forward in this enumeration and makes moods spring forth through the alchemy of his writing. At no point is there any dialogue about what the state is, but we know that, for the young girl, the state seemed like a stern master without more, suddenly rebelling like a cruel parent. Since she was a child, she had been inoculated with A certain confidence in the state, present in a way that was as incomprehensible as it was ubiquitous. One day, this father-state closes the perimeter of its citizens because they belong to it, and she will regret having spent so much time plucking the daisy, limiting herself to Importuning her more believing classmates with the cheerful music of Western radio stations…

Johnson would be remembered as the writer “of the German divide”, given his penchant for portraying in detail the points of union and disunity between the two idiosyncrasies.

She is an orphaned nurse and delighted in getting off the train as it passed through the western side and flouting the rules. She bought drugs for her hospital and practiced an easy form of smuggling. This had allowed her to flirt with boys from the other side, to be dazzled by the glitter of shop windows, to slip into capitalist seduction. But she is educated in rigor and knows well how to discriminate the lies of the other state; both he and she have different points of view, even a subtle competition. But politics do not drive them, but by a vague excitement sustained by the idea that their time was harmless, That they were in a period of peace and not on the eve of a Sunday when the state would impose its greatest desires with satisfaction.

Even after the Wall, the outrage will not be instantaneous. A vague curiosity about each other will continue to dominate them, the first stirrings of power: they will seek each other out without admitting that they are seeking each other out. He writes to her innocently and the mere receipt of his letter translates into a sanction for her: she is demoted in her job. They should rebel against injustice, but they won’t, why not? This is one of the many questions the novel seeks to answer. One could say that it is a novel about tedium, fatigue, and indefinition. Or about freedom and its tepid defence. Or about how much truth we can tolerate without collapsing.

He is a freelance photographer and lives in the drift of his desire. He drives sports cars beyond his means and has cultivated the art of notoriety. Several times he will go into the other Berlin saying that he is looking for his car, which has been stolen, but Johnson leaves us clues that he is looking for something else that he dares not name. The author of Gruppe 47’s prose is so restrained and tightly bound to what is happening that it is a gift; he leaves it to us to judge every emotion and act.

Building the Berlin Wall.

The plot moves forward like the Spree itself, the source of the canals that open up Berlin, which meanders through the city without a current, sometimes even backward. It is a slow plot because it obeys the apathy of the protagonists, the eternal postponement of their decisions, and the doubt that has colonised them. No one has a destiny painted in pencil, clear, tragic, or epic, but no one had made me notice it until I read this novel. Most of us swim in a fog populated by chance, and few are the acts that genuinely belong to us. This lukewarm, untroubled state of mind, in which we do not take charge of our freedom, nor look it in the face: may allow a wall to rise in any city overnight.

Fascisms easily penetrate us while we are distracted by routine, everyday miseries, nursing protocols, or buying a better car. Johnson describes it perfectly: those blurred and cowardly states of mind into which violence or an authoritarian regime can slip without finding resistance. In the early hours of a Saturday morning, the price of choosing a life of coherence and justice becomes impossible and will be “a vexation that cannot be avenged…”.

The nurse is unaware of her burning desire to move freely in a world that constantly excites her and offers her endless things, novelties, modernity, progress, spontaneous gestures far removed from Soviet rigidity. Unaware of her desire, unaware of her frustration, and having put her spirit to sleep so as not to suffer, she navigates without decision between security protocols, quarrels between colleagues, and a detached and tragic mother who does not know how to console her. She hesitates in the face of distant siblings who do not fight for the nest either, and the ignorance of her real desire, this neglect of herself, combines with the destiny that the young Westerner prepares for her from the other side: when she learns of the offer, she will adopt it ambivalently, lukewarmly, without telling herself that something is exciting to stake her life on.

For his part, the young man who longs for her will wander around Berlin in a state of slumber, scorning his time and savings, defying his phobia of airplanes, squandering masculine vanity, and camera shots. He will dread the discovery of his impotence, his poverty of origin, and the trembling child that inhabits him, and he will not admit the emptiness that moves him aimlessly.

I would like to know what Johnson would write about us now, more distracted and fallacious than we were then. Perhaps we’re more thrill-seeking, and our only experience of risk comes from video games.

It is said of Uwe Johnson that he contributed to German Literature with a capital A, he recorded the germinal life of post-war Germans and was avidly read on both sides of the border. In this novel, I find it brilliant how he portrays the apathy of his characters, inexperienced, frightened young people who are reluctant to take sides in their personal lives and in public life. Her Western photographer sometimes comes into contact with her swagger, her absurd eagerness to be in the limelight, and how much she is afflicted by loneliness. She wakes up one Sunday to the betrayal that Constricts her breath, tightens her throat, sees the Wall, and knows that she deluded herself into believing she had infinite time to think about what world she wanted to live in. Perhaps, as the novel seems to explore, what will last forever is the definitive separation of two incompatible ways of life.

What is most remarkable about this novel is Johnson’s way of painting how terror seeps through these undefined lives, and how easily we succumb to mental laziness or extreme fatigue. If one is robbed of desire for years behind a wall: what else won’t happen to us? Any walls that exist today without barbed wire, watchtowers, or dogs, are equally segregating walls: the terrible thing is that there is no pickaxe to tear them down.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!