Brady Corbet premiered at the 81st Venice Film Festival The Brutalist, a considerable work, whose specificity lies both in what it tells and in the calligraphy with which he writes a story of tycoons and artists, Europeans and Americans, poor and rich, Jews and gentiles, a tale of overcoming in the land of opportunities where you only have one, and those who offer it are the same everywhere.

We cannot watch The Brutalist without keeping in mind other films that succeeded or attempted to capture a visionary, struggling with his own family, himself or society. There Will Be Blood (2007), The Fountainhead (1949), or the more recent and regrettable Megalopolis (2024) tell stories that can be related in some way to that of László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a Hungarian Jewish architect, trained at the Bauhaus, who was deprived of his profession and almost his life by the Second World War. But if we were to make a connection, it would be with Paul Thomas Anderson.

Curiously, the name chosen by Corbet for his protagonist is not that of a real architect, but that of a character who has existed: the vandal who attacked Michelangelo‘s Pietà in 1972. In The Brutalist, a great commitment to one’s profession and a complex personality, which belong to someone subjected to the hardest tests with which existence examines us, take the form of parables, of symbolic rhetorical figures, some of evident transparency, in an amalgam that gives meaning to the cinematographic term. We find ourselves before a film that transmits with its background and stylistic choices a unity that, together with the magnificent interpretations, offers us a significant spectacle, where the spectator cannot remain passive, but must respond, to Tarkovski paraphrase Tarkovski, by joining the dots provided by the director, and recreating for himself what the screen proposes, points to or insinuates.

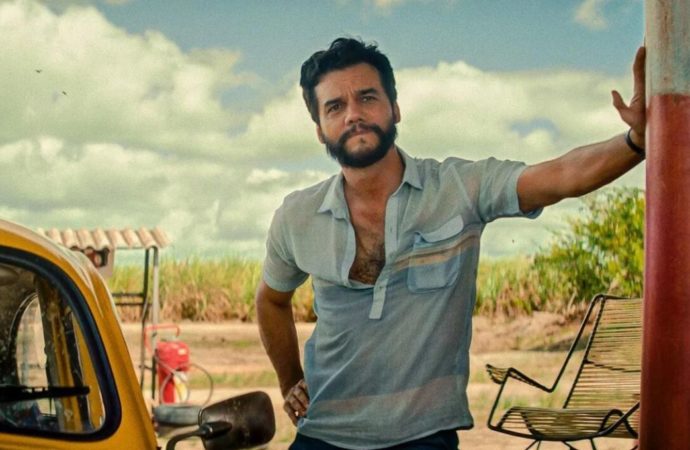

Adrien Brody and Alessandro Nivola in The Brutalist.

Lol Crawley‘s VistaVision photography (a system created in the 1950s) and Judy Becker’s design are part of the message, not just a wrapper. In the script, written by the director with Mona Fastvold, the struggle between two forces is present throughout the film: the struggle for survival and the will to stay true to oneself. Eating or selling out, keeping an addiction a secret and not living like a junkie, the apparent submission and the inner volcano. Even in the sex scenes, the conflict that emanates from Tóth’s complex personality, his psychological and emotional wounds, his sense of guilt and the will to live that have helped him to reach America is evident.

On the other hand, hypocrisy is another vein explored and ranges from the personal —the cousin Attila who takes him in when he arrives in America (Alessandro Nivola) and the tycoon Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce)— to the betrayal of the American dream, in a film of opposites, the major one, the European versus the American. The arrogance and angry insecurity of the nouveau riche —even if his surname of Dutch lineage represents old money in the New World— who considers any small chat with the architect as “culturally stimulating”, against the quiet pride and inextinguishable vocation of the creator, humble and at the same time with inexhaustible self-confidence.

Felicity Jones, Guy Pearce and Adrien Brody embody their characters with admirable depth and character. The protagonist of The Pianist is not simply a talented, malnourished Jew who finds his opportunity in America, as it might seem at the beginning of the film, as he develops into a multidimensional, complex and lively character.

The three and a half hour film, which was screened with a 15′ countdown break, is to the epic what architectural brutalism and the entire Bauhaus did to society, ridding it of filigree and endowing its habitat with meaning, beautiful, useful and meaningful. The gratuitous has no space between concrete and steel, and the second part opens with the arrival of Erzsébet (Jones) and her niece Zsofia (Raffey Cassidy), after a long wait to emigrate and join him. László’s wife is a force of nature, intelligent, wounded and a survivor, a type of woman the tycoon is not used to dealing with, breathing into the film and Tóth’s life a decisive breath of fresh air.

The narrative of the director of The Childhood of a Leader is neither linear nor detailed, neither schematic nor literal, opting for a wealth of images that, when monumentality is entrusted to the suggested, reach excellence. Brady’s audacity knows no limits and reaches its zenith in the episode in which architect and developer visit the Carrera quarry. Although he can be reproached for a too thick stroke, the intensity of the message borders on the inadequate to settle with a disturbing synthesis, perhaps with too many components in the combination: the raw exercise of power as soon as the occasion lends itself, abandoning salon manners, the passivity of the assaulted and his learned helplessness, also placing this sequence in the heart of a natural resource that represents the raw beauty, exploited and split.

As a climax, Corbet offers us an epilogue that takes us back to the eighties and the tribute to László Tóth at the Biennale of architecture, a coda perhaps unnecessary, equivalent to that final recounting of the fates of the characters of a melodrama based on real events. But above all, it seems to gratuitously fill in the gaps that the interpretation of Tóth’s designs did not ask for, revealing the symbols that enclosed his works, intimately related to his life and relationship with Erszébet and the consequences that the tragedy of the Holocaust marked in their future.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!