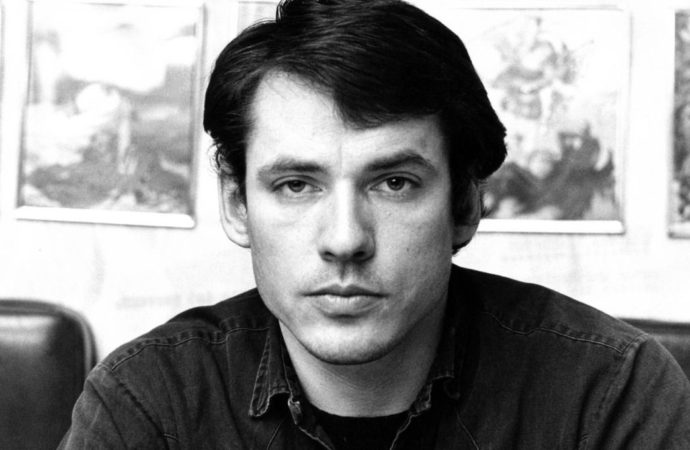

Kevin Costner presented the first chapter of his four-part, twelve-hour epic western in Cannes on 19 May. More than ten minutes of standing ovation filled the Grand Theatre Lumière with an emotional welcome. The fusion of classic Western film style with action cinema, historical perspective, and meticulous genre detailing make Horizon a delicate behemoth of independent cinema. It is a project conceived in the late 1980s to which the director, screenwriter, and actor has devoted golden perseverance. It is his personal bet of the moment and, as he usually does, he is gambling everything on it.

On multiple occasions, Costner has spoken of his childhood fascination with westerns. His acting relationship with the genre began in his thirties with Lawrence Kasdan‘s Silverado. In it, he played a skilled, charming gunslinger, who could hardly take death seriously and wasn’t afraid of a duel to steal a kiss from someone else’s girl. Five years later he directed, starred in, and also participated in the production of the Oscar-winning Dances with Wolves. A film that seems to have been shot in a state of grace, a project driven from scratch by a group of friends that exceptionally represents the triumph of inspiration and the all-or-nothing gamble. There, the serious and restrained but unpredictable Lieutenant John Dunbar turned the relationship between whites and Native Americans upside down.

In 1994, he returned to Lawrence Kasdan, this time also as a producing partner, to shoot the biopic Wyatt Earp, a character development film about the legendary gunfighter and sheriff who moved from one side of the law to the other. In 2004, he directed and starred in his project, Open Range, a delightful western about transhumant cattle ranchers in conflict with ranchers, their corruption, and an increasingly land-grabbing world. In 2013 he won an Emmy and a Golden Globe for playing the leader of the Hatfields clan in the miniseries about the legendary and bloody clash between two families on the Virginia-Kentucky border in Hatfields & McCoys, directed by Kevin Reynolds. And, since 2018, he has been the adored patriarch of the neo-western serial Yellowstone, which has broken ratings records in the US and put him on a national pedestal, returning for a Golden Globe in 2023. With such a resume, it’s understandable why he fits so well in the hat and holsters.

In Horizon, the western aesthetic reaches a supreme level with extraordinary cinematography and breathtakingly beautiful landscapes. As Kevin Costner explained at the Cannes press conference, there are places where he filmed when he returned a year later, there were already buildings. To have achieved these images is at least a contribution to the visual conservation of the territory.

The saga takes place over fifteen years of the process of occupation and settlement by Europeans of the current territory of the United States, with its Civil War in between, and focuses both on a macro-vision of the events and an intimate, everyday look at the harshness of the conquest. Hence the classic rhythm between the shots of immense virgin landscapes and the faces that show the vital map of the characters. Personal relationships carry as much weight, if not more, than the martial decisions of this historical process. Women, contrary to the marginality to which they have generally been relegated in this genre, take on a central and active role. As might be expected, it does not romanticize the appropriation of North American territory, but shows it as a time of widespread violence in which the extermination of native peoples was a devastating crusade. It was a world in which everyone had to protect himself and his own, the essence of the Western prior to the tutelage of a strong state. But despite the prevailing harshness, it does not forgo its moments of levity and humor.

In this first chapter, we find the presentation of several narrative lines that begin to intertwine in a relaxed way. Each takes its time, the script is in no hurry to tie them together, it is a long journey: a mother and daughter who survive the massacre and destruction of a Montana settler village by Apaches in defense of their resources; the internal bickering of the natives over whether to fight hard for their territories or succumb to the unstoppable invasion; an unscrupulous family clan in a small Wyoming town that bullies and murders for real estate; a lone cowboy (this is where Kevin Costner appears after 45 minutes of footage) who dispenses justice without seeking it and becomes associated with the escape of a prostitute and her child; a caravan of newly arrived Europeans crossing Kansas in search of a new life on the horizon; a group of thugs who train the youngest of the gang against all mercy and a chieftain who recruits Chinese to work on the railway with the demand that they do not use his language.

Horizon: an American Saga is an atypical production. It has a serial structure designed to be seen in the cinema, it is a declaration of resistance to the well of content that are the platforms of premiere. Each film will last approximately three hours and will be spaced out in installments. By now, the first two chapters will be released in Spain on 28 June and 16 August. The third part is in production and the fourth is pending financing. Dances with Wolves also made risky bets at the time. It was also atypically long, introduced subtitles in its original version to allow the Lakota to speak in their language for much of the film, and humanized the natives in a way rarely seen before. But if we talk about differences, the movie from the early nineties was shot in just over a hundred days, while the present one had to be shot in half that time.

It is impossible to dissociate Kevin Costner from Dances with Wolves and Horizon features which could be a nod to its precedent. The structure of the room, the placement of the characters, and the positioning of the camera are all similar to that mythical scene in which Lieutenant John Dunbar, after his promotion for having destabilized the opposing side by ‘flying over’ the battlefield on horseback without suffering a scratch, goes to receive instructions about his destination on the frontier to listen in astonishment to a deranged superior who ends up shooting himself in the head leaning out of the window. This time, though, the situation is different, and the scene has no dismal end.

There is always something epic in the feat of history and the cinematographic construction of a country’s identity, but what can we say about the feat of a vital project of such characteristics and dimensions?

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!