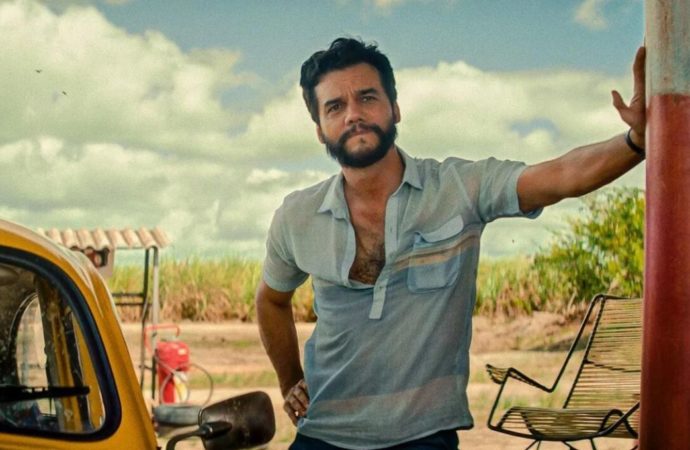

British director Andrea Arnold, three-time winner of the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival with Red Road (2006), Fish Tank (2008), and American Honey (2016), presented Bird in competition at the 77th edition, two years after releasing the superb documentary Cow (2022) and directing several episodes of Transparent and Big Little Lies. The cast is led by Nykiya Adams, playing the protagonist, Bailey, alongside Barry Keoghan, as her young father, and Franz Rogowski, playing the young man who turns her world upside down, her unsatisfactory everyday life and breathes a breath of confidence into her yearning to ‘fly’.

Arnold’s portraits are as accurate as they are meticulous and fluid. In the case of the characters that populate Bird, he presents us with a squat family with two children trying to get by as best they can, within the patterns of petty crime, of which we are only given anecdotal information, but which is held together by a loving and patient father (who was a teenager), within his limitations. Bailey’s mother, on the other hand, lives with her young children in another home, disengaging from her, and maintaining an abusive relationship with a violent man. At the same time, all the siblings seem to have a close relationship, despite everything. However, Keoghan’s character is not well-defined, his bonhomie and immaturity are underdeveloped, and as for the protagonist, we must choose to believe in her precociousness. The Oscar winner for her short film Wasp (2003), through Bird, enters the realm of metaphor and magical realism, with a protagonist who evolves throughout the film, recreating in her performance an emotional arc, resulting in a very particular coming-of-age.

Bailey lives in a world torn between that which reflects her sensitivity and that which stimulates her rebelliousness. Still, she is not yet able to combine the two nicely, as she is only just leaving puberty at twelve.

The appearance in her life of a stranger—the perfect ambiguous, and lovable Rugowski— who is received with suspicion and antipathy, will be the touchstone of an unexpected evolution for Bailey. The mysterious character who emerges in the middle of nature – where she feels safe – has returned after many years to her hometown, to reconnect with her family, who had disappeared when she was a child. The emotional parallels with the young woman’s situation become more evident when the father rejects him. But it is through their encounters, which could well be typical of a Miyazaki film, that she begins to glimpse a different picture and feel more self-confident.

Bird‘s display of fantasy, far from disconcerting, seems organic, in the same way that we symbolically perceive reality. And that is how Bailey experiences it, as a reflection and a model of resilience when her identity in terms of all that defines her is blurred. Child and woman, feminine but masculine in the emulation of a survival mode, mature but childlike, with half-blood brothers, she discovers that her strategies no longer serve her, that entering the adult world cannot be a struggle to be the toughest, because bitterness limits her and also confuses her. Bird bursts in out of nowhere, dressed in skirts, a small rucksack, and all the serenity and patience in the world, in brutal contrast to Bailey. Afterward, it will be his sheer presence on the rooftop overhang, where he waits undaunted, a message as obvious as neon, as revealing as a manual.

The anguish at her father’s wedding is the touchstone that puts Bailey on the ropes, an opportunity to be assertive and rebellious, but it is that very event that will ultimately reveal the transformation she has undergone thanks to that lovely, winged presence that protects her by its very appearance. Andrea Arnold shows in Bird that there is hope and that being special and sensitive in such a cruel world is not necessarily a condemnation, even if it may require fantasy.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!