From 28 August to 27 November, the Basilica of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice is hosting an exhibition by the artist Ai Weiwei entitled The Human Comedy. Memento Mori. The large central aisle, the choir, the sacristy and the Benedictine monastery display his works made with different techniques and materials, such as porcelain, wood, glass and LEGO pieces. Among these is the monumental chandelier that occupies the entrance, measuring nine metres high and six metres wide. The largest hanging work ever made on the Venetian island is a waterfall of Murano glass, a material with which he began experimenting in 2009, which reminds us of the futility of life with its deep black colour, skeletons and skulls that compose it.

Photo ©EL HYPE

Three years were needed to create this fantastic sculpture, which was built in collaboration with Studio Berengo, and although it was begun before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese artist and activist conveys a reflection on the human condition that resonates on a planetary level. The central work of the exhibition is composed of 2,000 pieces of matt black glass —dramatically illuminated by Luce5 —where the human and nature intertwine with a singular effect that appeals to our senses, as a brilliant introduction to the rest of the works on display. Berengo’s participation is due to his interest, for thirty years, in establishing collaborations with artists, being inspired by the projects promoted in the sixties by Peggy Guggenheim and Egidio Costantini, which resulted in works in glass by Picasso or Chagall.

Photo ©EL HYPE

The architect Palladio designed the great church of the convent, whose general structure was completed in 1576, and where he sought vertical continuity in the elements of the order, avoiding easy solutions and achieving as a result a grandiose building, connected with the great works of Roman architecture. The soul of the temple that has welcomed this cascade of bones, skulls and organs, has enveloped the contemporaneity of a spirit of permanence, with the serenity of a portentous space that takes root in all of us who contemplate it, overwhelmed. We look inward, believing we are looking outward, because Weiwei conveys to us the mystery of existence, including us in chaos, in transience, in finitude, which paradoxically is what connects us through the ages.

Photo ©EL HYPE

The dialogue between the walls of spirituality and the materiality of art has a continuation from the Tintoretto paintings it houses, such as The Last Supper, to the modernity of a contemporary artist. The 2,700 kg piece, which was first shown in Rome last March inside the Baths of Diocletian, has returned to the city that created it to express the mutability, the brevity of our lives and the need to engage in a more beneficial interaction with our environment. In the artist’s words: The chandelier is a glamorous object to be displayed in the home, for example in a living room. It is my need to include death in our everyday life, to connect an interior design object with what is happening outside the home, in the world.

The Venetian exhibition has been expanded with eight new, previously unpublished works in glass, such as Brainless Figure in Glass (2022), a self-portrait combining technology and craftsmanship: Glass Root (2022), which reminds us of Weiwei’s work in wood, following the discovery of deforestation remains in Brazil in 2017; and everyday objects, such as Glass Takeout Box (2022), a symbol of globalisation, which he already presented in marble in 2015, and Glass Toilet Paper (2022), a reflection of our social fragility. Glass, a special material and a part of our daily life, bears witness to joy, anxiety and worry in our reality. In its presence we reflect upon the relationships between life and death, and between tradition and reality.

Illumination. Photo ©EL HYPE

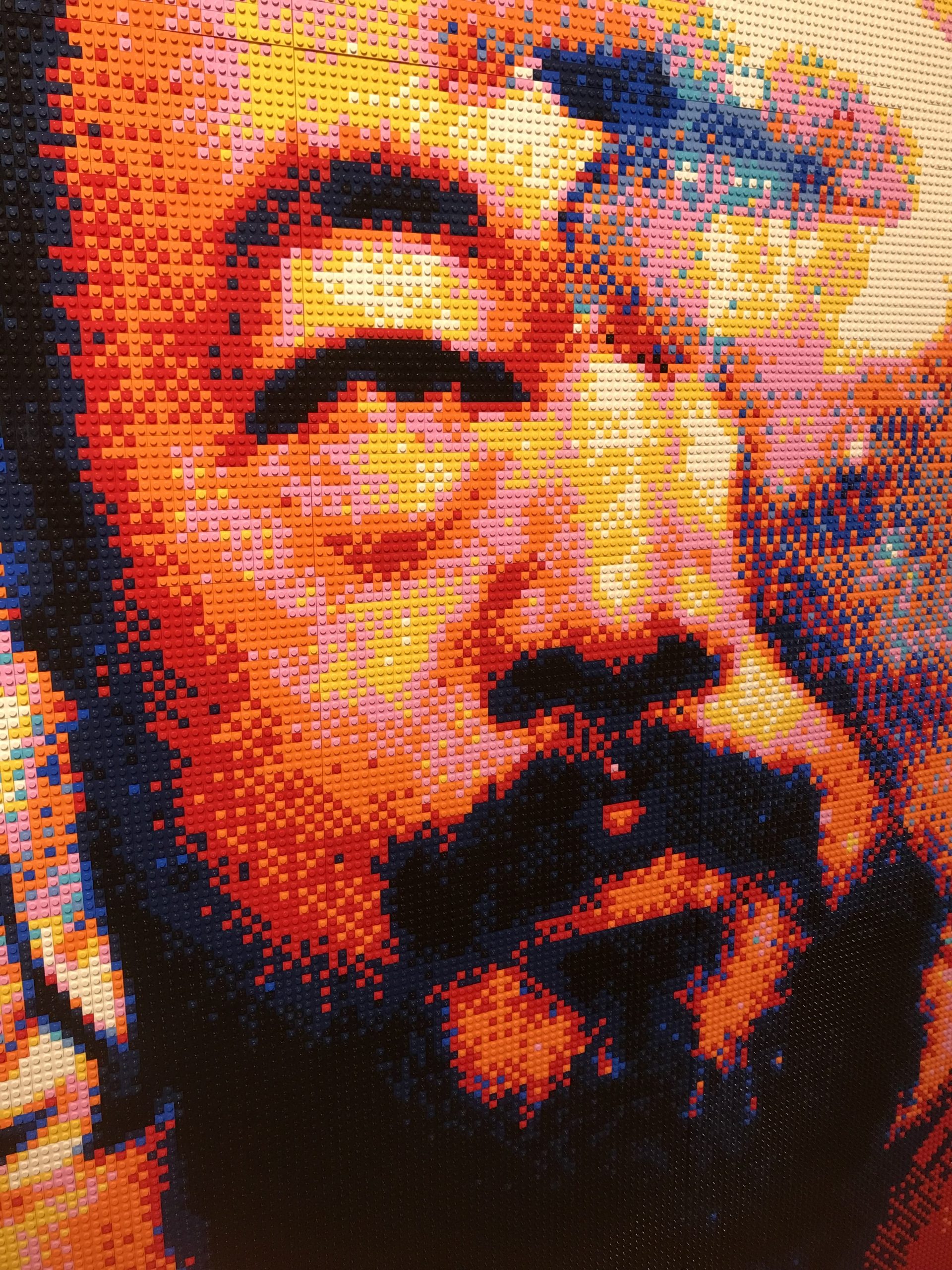

Also on display at the Benedictine Abbey are several LEGO pieces by the Chinese artist, such as the iconic selfie of Illumination, 2019 (Lisson Gallery), taken in Chengdu in 2009 while being escorted by the police to a hotel lift, as well as some of the more recent ones such as Sleeping Venus (After Giorgione), 2022, Know Thyself, 2022, and Untitled (After Mondrian), 2022.

Illumination, detail. Photo ©EL HYPE

The exhibition, curated by Ai Weiwei, Adriano Berengo and the director of the Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore, Carmelo A. Grasso, speaks of death in order to celebrate life; it does not plunge us into loss, although it reminds us of it, or into the meaninglessness of existence, but encourages us to celebrate, even from our own destitution.

Brainless Figure in Glass . Photo ©EL HYPE

Our fleshless limbs remind us at every moment of the miracle of being alive, beyond broken bones, as the artist reminds us, The human comedy shows the liberated content of a human body: our open interiority, the entrails of life laid bare and exposed for all to see, our mortality expressed by the multiple parts that define our very form.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!