Before the 1980s, only God had been allowed to write the early history of Islam. On at least one occasion, the Devil may have tried to dip his quill in His ink, but, if the legend of the ‘satanic verses’ is right, he was soon subdued. Only He who makes things happen has the right to make them happen differently.

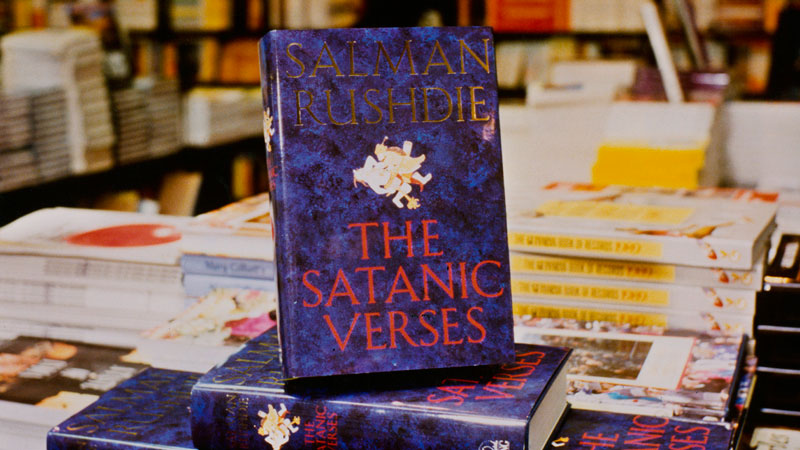

In 1988, an Indian-born British citizen, Salman Rushdie, neither a god nor a devil but fairly in between, tried to challenge God’s monopoly over His work. As we know, he was sentenced to death. Author’s rights are no laughing matter.

But the damage was already done. Doubts were raised like a cloud of sand. What if Rushdie’s account of the days of the Prophet is, to some extent, in some respects, even in a single detail, closer to the historical truth than (say) al-Bukhari’s? Is there a way to prove that one writer got everything right, and the other everything wrong? Isn’t literature a shadowy King Midas, in that everything it touches becomes similarly foggy, tortuous, and puzzling?

Seeds of fiction were planted in the cracks of historical knowledge. Certainty was the first victim, but they also threatened something undoubtedly more important: the sense of wonder and elation of believers when that history is of a spiritual or archetypal nature—when it is not just history, but a people’s story. When it is embraced not just because the facts support it, but because it somehow supports us.

Can art be the third principle that mediates between the material and spiritual worlds?

Growing his own, personal literature in someone else’s narrations of the past, Rushdie might be thought of as a parasite in them. When he re-enchants the post-modern London and Mumbai of his characters with visions of the beginnings of their (and his) ancestors’ religion, he is, at the same time, disenchanting that religion. Milking a (holy) cow that he refuses to feed. How can an author repay that debt? How can he make up for degrading religion in the interests of a novel? For translating sacred history into fiction? Miracles into mere dreams? Or is the sense of transcendence not necessarily lost in translation…?

In 1990, one year after the fatwa on his head, Rushdie ordered his thoughts on the controversy in a stimulating lecture. Building on his extreme personal situation, he addresses what he regards as the main question of the secular, materialistic West: “Is Nothing Sacred?”

He [Carlos Fuentes] then poses the question I have been asking myself throughout my life as a writer: Can the religious mentality survive outside of religious dogma and hierarchy? Which is to say: Can art be the third principle that mediates between the material and spiritual worlds; might it, by ‘swallowing’ both worlds, offer us something new—something that might even be called a secular definition of transcendence? I believe it can. I believe it must. And I believe that, at its best, it does.

In the past two centuries, art has been proposed, time and again, as a remedy for a life that would otherwise be unbearably bland or brutal. Romantic philosophers, plus the pretty unromantic Friedrich Nietzsche, invoked a future where the creative urges of human beings would shape reality the way only God’s will was formerly supposed to do. The avant-garde artists of the early 20th century walked the philosopher’s talk, bringing aesthetics to every domain of life and death. This was, and still is, seen by some as a sign of the times, a product of that fin de siècle so prone to existential angst and nihilistic despair.

However, in 1983, in one of his last interviews, one of today’s most cited philosophers, Michel Foucault, expressed an uncannily similar view:

What strikes me is the fact that in our society, art has become something that is related only to objects and not to individuals, or to life. That art is something which is specialized or which is done by experts who are artists. But couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art? Why should the lamp or the house be an art object, but not our life?

One century after Nietzsche’s mental breakdown, Foucault and Rushdie were confirming that his was not pure folly. The marriage of art and life still had an enthusiastic offspring.

***

In Mexico, surrealism runs through the streets. Surrealism comes from the reality of Latin America.

So said Gabriel García Márquez, the magic realist Colombian writer and 1982 Nobel Prize winner. Mexico was similarly praised by the likes of André Breton and Salvador Dalí, who reportedly vowed never to return because he couldn’t Stand to be in a country that is more surrealist than my paintings.

Why is Latin America so surrealistic, according to leading authorities in the field? And why are Indo-Anglian authors, like Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, or even R. K. Narayan, so close to magic realism? Does it have to do with their dual culture? Were Latin Americans, Anglicised Indians, or secular Egyptians among the first to experience, through cultural and political suppression, the same loss of meaning that European intellectuals have reported since the late 19th century? Would Nietzsche have been jollier had he spent his summers in the Andes instead of the Swiss Alps?

It would seem that magic realism is a spring that erupts unexpectedly wherever the fields are covered by concrete. If you condemn a race to one hundred years of solitude, they will come up, sooner or later, with one thousand stories.

The Satanic Verses, an epopee of dreams, visions, and transmutations, presents literature as the last bastion of miracles in the modern world, and shows how stories that go down in collective memory can develop a life of their own, and even threaten to replace older ones. This literary gap is what allowed Rushdie to play with the history of his ancestral religion, and it is also the most blasphemous and potentially dangerous thing his book has to offer. The exaggerated reaction it received only managed to prove him right.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!