Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Graues (Nosferatu, a Symphony of Horror, F. W. Murnau, 1922) is one hundred years old, once again demonstrating its ability to stand the test of time. This timelessness means that it is now considered one of the most representative films of German expressionism, alongside The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis.

Of the many monsters that populate folklore and popular culture, vampires are definitely the most blood-curdling. Throughout history, from the vrykolakas of the Hellenic world to the concept of the contemporary blood-sucking undead, their shadow has been looming over the minds of the public, making an appearance in their most terrifying nightmares. There are many names for these creatures, but the one that sends the most chills down the spine is the title of German director Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau‘s most famous work: Nosferatu.

Nosferatu is a recurrent cult term, both in film and literature, to refer to these beings from beyond the grave, although it is only mentioned twice, and only very superficially, in Bram Stoker‘s famous Dracula. However, it is worth bearing in mind that, despite the impression that may be conveyed by the perception of this word, its origin is hardly memorable. The term in question was found by the Victorian author in Emily Gerard‘s essay Romanian Superstitions, where it is presented as the Romanian expression for vampire. However, the term does not exist in any other language. The explanation that can be given for this inconsistency is the author’s lack of knowledge of Romanian, which may well have led her to make a transcription error, mistranslating the adjective nesuferit, the real meaning of which is infested.

Yet despite its humble origins, the trio of producer Albin Grau, director F. W. Murnau and screenwriter Henrik Galeen elevated the term nosferatu into popular language. They succeeded in endowing it with an overwhelming charisma, and it was used repeatedly in subsequent adaptations.

To say that this is a pioneering film in horror cinema would be frivolous, as it would mean ignoring the key artistic elements that make it up. It would mean not taking into account the time in which it was made, the predominant artistic culture of post-war Germany, the worldview of its creators, or the symbolism present in its shots. Nosferatu is more than just a brilliant and pioneering horror film, it is a mirror through which we can see the different cultural currents prevailing in the interwar period and the first steps of contemporary cinema.

A project shrouded in the cloak of esotericism

Although the first name that resonates in the collective mind at the mention of Nosferatu is that of its director F. W. Murnau, the main person responsible for this great project was none other than Albin Grau (1884-1971), who was the costume and set designer as well as producer. He was also the one who introduced the whole esoteric and occult conglomerate of the film, elements that make it unique and pioneering in the history of horror films.

After fighting on the Serbian and Russian fronts in World War I, Grau began to frequent various esoteric circles in Berlin, taking up the position of Grand Master of the Lichtsuchenden Brüde Lodge. He began working in the film industry as an illustrator and publicist, which led him to meet Murnau, to whom he proposed directing his adaptation of Dracula, a project for which he would go on to found Prana Film.

Logotipo de Prana Film.

The name of the production company, Prana, shows Grau’s interest in the occult sciences, referring to a Sanskrit term (liturgical language used in creeds such as Buddhism, Hinduism or Jainism) relating to the vital force present in all living creatures.

This esoteric concept is clearly associated with the image of the vampire in the film, conceived as the creature that feeds on the blood or vital energy of the living. This idea of astral entities, arising from the dark thoughts of human beings, responsible for epidemics that call for blood sacrifices in order to prevent them, is closely linked to that of the alchemist Paracelsus, whose figure is embodied in the character of Professor Bulwer (Abraham Van Helsing‘s counterpart). This is made concrete in the film in the plague epidemic that spreads through the city of Wisborg, which cannot be remedied by scientific methods, but by the blood sacrifice of a woman, thus destroying forever the dark being responsible for this catastrophic situation.

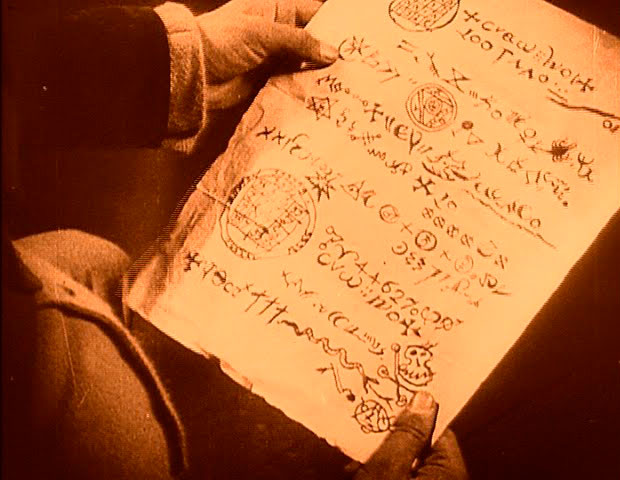

Not only its name is revealing about Prana Film, but also its logo, the symbol of Yin and Yang, another element of esotericism in which light (wisdom, knowledge) triumphs over darkness (ignorance). However, this element is not only confined to conceptual foundations but is also seen in visual elements, such as the letters exchanged between Orlok and his minion Knock, laden with indecipherable symbolism, probably heavily influenced by esoteric codes.

The letter with esoteric symbols.

The shadow of the occult would continue to hover over the Nosferatu legend as time went on, as in July 2015 Murnau’s grave was desecrated and his corpse decapitated. In the vicinity of the niche, traces of wax were found, indicating the possibility of some kind of secret ritual.

The filming: Murnau’s worldview

The name of F. W. Murnau occupies an emblematic place among the pioneers of the seventh art, his works being a source of inspiration for future creators, and, obviously, Nosferatu would be no exception.

Like other virtuosos of film directing, Murnau led the shooting of the film with an iron fist, taking his stubbornness and obstinacy to the limit, even endangering part of the production team, as well as the actor Wolfgang Heins (who played the captain of the Empusa), who ended up covered in rats after opening the coffin during the filming. But it was not only the integrity of those responsible for the production that was undermined, but also that of the cameras, by using them in natural landscapes in broad daylight, in order to lend veracity to his symphony of terror. He even used the use of speeding up and slowing down, as well as the projection of the film negative to represent the transition from the world of humans to the vampire’s world beyond the grave.

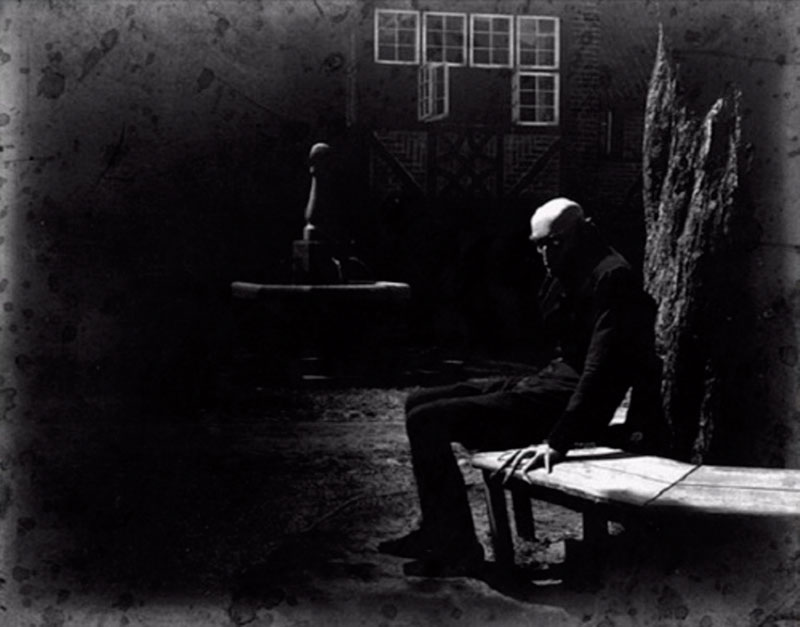

Don’t get carried away by the terror that this photo may inspire. It’s just Max Schreck relaxing during filming.

This preference for natural settings means that the category of “expressionist film” is not entirely appropriate for this film. These settings, in contrast to the two-dimensional scenery of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari or the artificial-industrial atmosphere of Metropolis, together with the symbolism influenced by the esoteric, make the aesthetics of Nosferatu closer to the landscapes of German Romanticism, together with other avant-garde trends such as symbolism, magical realism, and Art Deco, among others. All these elements would make Nosferatu an island within German cinematic expressionism.

Orlok: the bird of ill omen

Over time, cinema has distorted the figure of this nocturnal monster, from the film starring Bela Lugosi in 1931 to the vampire-clown of Twilight, via the Hammer versions and the more romanticised version by Francis Ford Coppola.

All these films offered a portrait of the vampire as a monster with a sexy and cold countenance, brimming with elegance, generating in the spectator a dilemma between accepting an erotic bite and joining them in an immortal and sinful existence or showing a forceful refusal to remain on the side of good. However, such a perspective was based more on John Polidori‘s more sophisticated and seductive The Vampire than that of the Count of Transylvania.

Bela Lugosi as Dracula.

Nosferatu was the first time that the renowned monster created by Bram Stoker was given a cinematic face and, despite the film’s numerous plot licenses, its image of the vampire is to this day the closest to the essence of the original villain. Murnau went even further, offering a vampire whose repulsive physiognomy and insect-like mannerisms made him more like a vermin than an attractive bloodsucker. Orlok, due to his cursed nature, was also an infectious personality, causing him to be surrounded by rats and causing a plague of pestilence wherever he went.

Yet, just as the vampire played by Max Schreck and the Transylvanian Count share many characteristics, there are also many differences between the two. For example, Orlok’s bites, which do not turn his victims into vampires, but cause their death due to the absence of blood in their bodies. Another notable disparity with respect to Stoker’s novel is that in Nosferatu the only way to destroy him is by exposure to the sun, which makes him disappear in a cloud of ashes and fire.

Max Schreck as Orlok.

Nosferatu, more than an undead devourer of humans, is a spectral presence, more spiritual than physical, with Paracelsian parameters. It is a bird of ill omen whose curse is not based on its own monstrosity, but on the trail it leaves behind it, constituting an infectious focus, a grim parasite from a world alien to ours that awakens our deepest fears and most primitive superstitions.

With all of this, the German director achieved a unique accomplishment, creating a character who is profoundly close in essence to the one depicted in the original novel, but with a series of striking differences that give him a personality and identity of his own. With an ingenious combination of plot fidelity and creativity, the most original vampire in the history of cinema was born.

Florence Balcombe and the crusade against Nosferatu

After Abraham Stoker’s death, it was his wife Florence Anne Lemon Balcombe (1858-1937) who took on the role of guardian and protector of her husband’s work and legacy, which is why, after the premiere of Nosferatu, she aggressively crusaded against it. However, this did not mean that she was radically opposed to her husband’s novel being adapted to other formats, as three years after the filming she allowed the Hamilton Deane company to adapt it for the theatre, and even authorized Universal to make a film of the same name directed by Tod Browning and starring Bela Lugosi.

Florence Balcome.

Murnau’s adaptation, however, generated a profoundly different reaction in the widow’s heart. On the one hand, the film showed no plot rigour with respect to the original story, introducing radical changes to the plot and renaming its characters, with Harker becoming known as Hutter, Mina as Ellen, Professor Van Helsing as Professor Bulwer and Renfield as Knock. There were also elided characters, such as Lucy Westenra, her fiancé Arthur Holmwood or the Texan Quincey P. Morris. All these modifications were conceived by Balcome as an outrage, a feeling that would lead her, thirsty for justice and money, to carry out her fight against Murnau and his film.

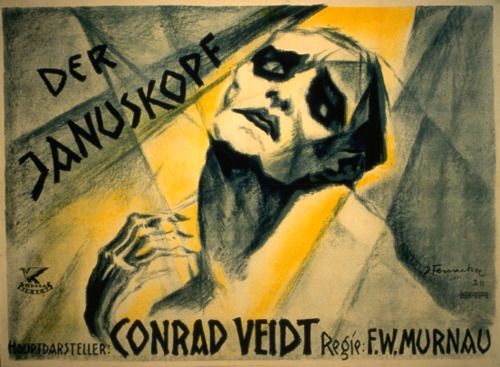

Shortly after making her decision, Ms. Balcombe received a letter from Germany, which included newspaper clippings stating that the film was a free adaptation of Henrik Galeen‘s Dracula. This was not the first time that a free adaptation of a British Gothic literary work had been made, as two years earlier, Murnau had offered his own version of Robert Louis Stevenson‘s classic, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (Der Januskopf, 1920), without any legal consequences.

Póster de La cabeza de Jano de Murnau.

Balcombe would not surrender in his war against Murnau and his vampire, and shortly after Nosferatu‘s release, he joined the Society of British Authors. For the next two years, the society and its secretary G. Herbert Thring were harassed by several letters from the widow demanding action against the director and his fraudulent adaptation. At first, the secretary informed the plaintiff that the existence of a German publisher of the novel did not imply an obligation as regards the transfer of film rights.

Whether or not the lawsuit was successful, the Prana production company was in a very adverse financial situation. These unfavourable circumstances meant that in the same year that Nosferatu was released, the production company declared bankruptcy, unable to meet Mrs Stoker’s financial demands. Despite the widow’s many wiles, the symphony of terror would rumble through cinemas in Germany and around the world in the years that followed.

Unable to collect compensation, Florence decided to pursue the administrators of the production company’s assets, causing the expenses incurred by the Society of British Authors for this legal battle to become increasingly high. In this context of persecutory obsession, the production company’s lawyer offered a share of the box office takings and to be screened under the title Dracula, an offer that was rejected. Two years later, the court ruled in the widow’s favour, and she demanded a sum of five thousand pounds in exchange for the transfer of the rights to the new managing body, the Deutsche-Amerikanisch Film Union. The DAFU rejected the offer, lodging an appeal which they would lose only to appeal once more.

Abraham Stoker, author of Dracula.

This marathon of failures led the widow to realise that she would never get a single penny for Murnau’s work, so the problem took on personal dimensions, causing Mrs Stoker to demand the confiscation and subsequent destruction of all copies of Nosferatu. The DAFU would accept the sentence, so the original negative would be destroyed, as well as the copy sent to London in 1925 to The Film Society. The copy sent to the United States was given to Universal to begin production of Browning’s Dracula. Florence Stoker, having signed over the rights to the novel, demanded the destruction of the copy, and her wishes were fulfilled.

Despite their best efforts, it was clear that there was no guarantee that all traces of the film would be removed. During the time that the lawsuit was going on, the shadow of the vampire was screened in Japanese, Spanish, American, French cinemas… It was clear that Nosferatu was here to stay in the annals of the history of the seventh art.

A cursed movie?

It is common in popular film culture to associate curses with the occult and/or spiritualist-themed films, a condition closely related to mysterious events that occurred during or after their respective shootings. There is The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1971), with nine dead crew members, sets on fire, film reels mysteriously developed, and Ellen Burstyn suffering a back injury. The same goes for Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982), whose two lead actresses, Heather O’Rourke and Dominique Dunne, died at the ages of 12 and 22 respectively, linking the curse to acts of blasphemy and desecration.

Max Schreck.

Nosferatu, a symphony of terror, obviously, with the enormous doses of occult science it contained, could not be free of the category of a cursed film. One of the most widespread rumors about the film revolved around the figure of the actor Max Schreck, who played the vampire whose surname, Schreck, is German for fright or fear. His spectacular performance, his unrecognizable face covered by excellent make-up, and his lack of fame abroad generated a series of speculations that led to the wildest rumor in the history of cinema: Schreck was a real vampire. While it is true that he was never a blood-drinking monster, the brilliant actor died of cardiac arrest at the untimely age of 57, a tragedy that could be considered a cursed event.

The film’s screenwriter, Henrik Galeen, after his involvement in iconic productions such as The Golem, The Student of Prague, Mandrake, Das Wachsfigurenkabinett and Salon Dora, left Germany in 1933 with the arrival of Nazism in the chancellery. He lived in Sweden, England and the United States, where he died in 1940, without having made another film. Gustav Wangenheim, who played Hutter, also fled his native country because of his communist militancy. He was taken in by the USSR, where he worked as a scriptwriter and film producer. At the end of the war he settled in East Germany, where he worked for Deutsche Film AG as a screenwriter and director.

Alexander Granach, who played Knock, also fled to the USSR because of his Jewish origins and anarchist ideas, from where he also escaped to Hollywood. In the Mecca of American cinema, because of his thick accent, he would be condemned to play Russian and German villains, as in the romantic comedy Ninotchka. His co-star, John Gottowt, also of Jewish descent, fled to Poland, where, after the Nazi invasion, he remained in hiding disguised as a Catholic priest. He was found and murdered by SS officers in 1942. The real curse bore a single esoteric symbol: the swastika.

John Gottowt

However, the gruesome event that most fanned the flame of the Nosferatu curse rumour revolves around the mysterious death of its director, F.W. Murnau. Murnau. Like many other icons of German cinema, Murnau fled to the United States from the Nazi terror, but unlike Galeen, he continued his film career, eventually releasing one of his greatest gems, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), which would go on to win three Oscars in its first-ever run.

Just two weeks before the release of his last film, Taboo, Murnau died in a car accident with his fourteen-year-old Filipino servant, Garcia Stevenson. Kenneth Anger states in his controversial book Hollywood Babylon that, after that fateful event, rumours spread that it was the young man who was driving the car and that, just before the car left the road, Murnau was performing fellatio on him. Gossip that arouses our most morbid interests and makes us forget virtues such as rigour and criticism.

The legacy

Due to its potential to frighten audiences, the vampire has become a recurring character in horror films. However, the image of the vampire as a spiritual and esoteric being was never again present on the big screen until 1993, when Werner Herzog released his famous remake Nosferatu: Phantom Der Nach, 1979. In this version the antagonist was named Dracula, but the idea of the vampire as a dark spirit was revived, a conception that is embodied in the dreamlike visions of Harker (played by Bruno Ganz) in which he sees the vampire in a bridging situation between two worlds. The film won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale.

Klaus Kinski and Isabelle Adjani inNosferatu: Phantom Der Nach (Werner Herzog, 1979)

Although with his film Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1991) he returned to the vision established by Tod Browning, Francis Ford Coppola also included elements from Murnau’s work, such as the vampire’s shadow with a will of its own and the epistolary style as a nod to the original novel.

However, despite the marginality of this vampire image, tributes to Murnau’s work have not ceased in the seventh art, proof of its more than unquestionable impact on popular and cinematographic culture. In 2000, Shadow Of The Vampire (E. Elias Merhige, 2000) was released, telling the story of the making of Nosferatu based on the rumour that Max Schreck was a real vampire. Willem Dafoe‘s excellent performance earned him a Best Actor nomination at the Oscars, Golden Globes and Screen Actors Guild.

Fourteen years later, the hilarious horror-comedy What We Do In The Shadows (Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, 2014) was released, paying homage to the different vampires in film history, including Murnau’s, represented in the character of Petyr, who dies, in fact, in the same way as Murnau’s bloodsucker: scorched by sunlight. It has recently been confirmed that Robert Eggers, director of The Northman, will direct a new remake of Nosferatu, starring Bill Skarsgård, Lily-Rose Depp and Nicholas Hoult.

What We Do In The Shadows (Taika Waititi, Jemaine Clement, 2014)

In the world of animation, we also find nods to Murnau’s work, specifically in the film Shin Chan and the Mystery of Tenkasu Academy (Eiga Crayon Shin-chan Nazo Meki! Hana no Tenkasu Gakuen, Wataru Takahashi, 2021), where Shinosuke and his friends have to deal with a vampire extremely similar to Orlok, who instead of sucking blood, bites ass. Undoubtedly, the ultimate proof of a film’s immortality is the number of homages and remakes present in later works, even if they are films about Japanese children who have fun showing their asses to the public.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!