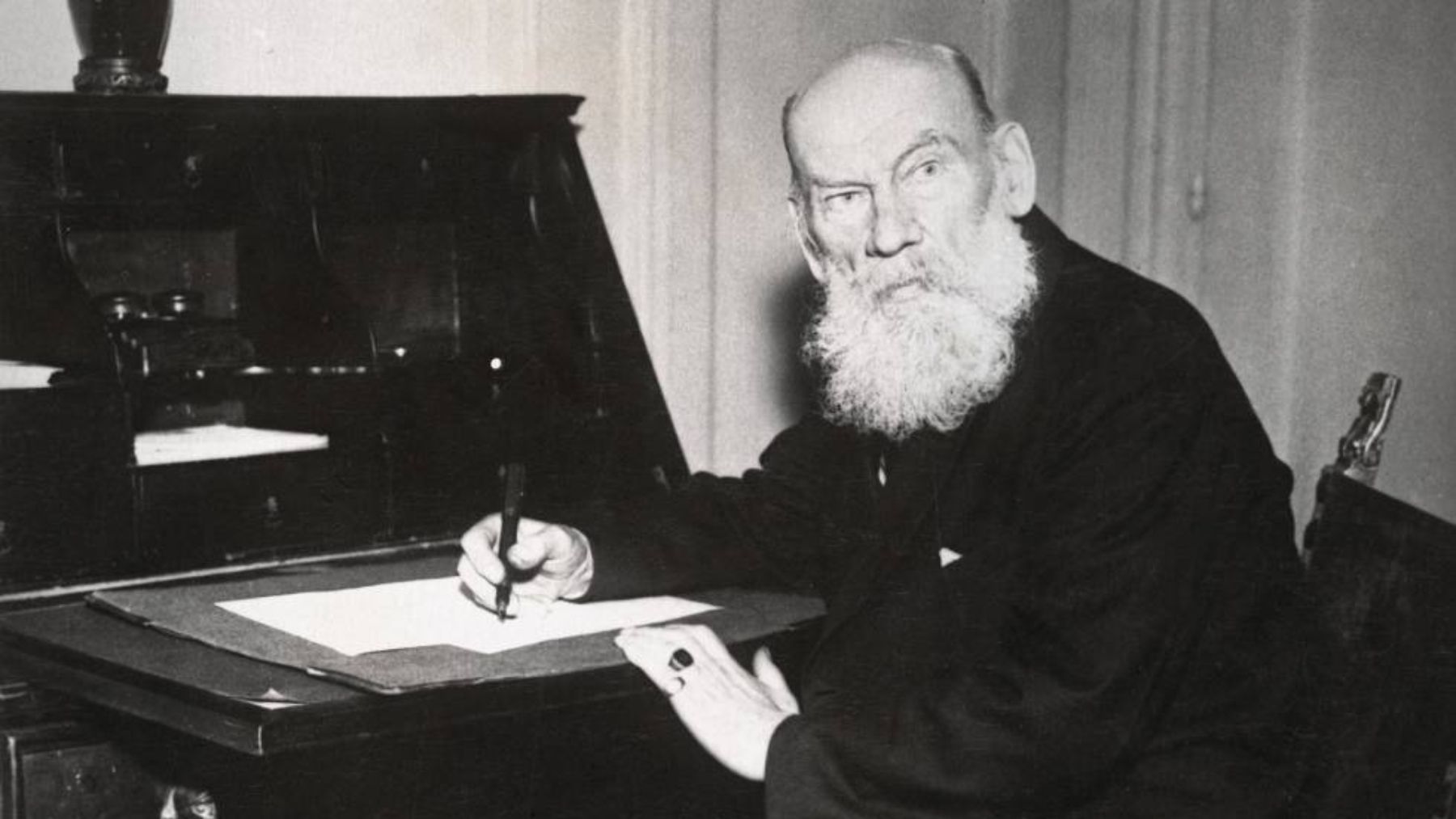

The Confession of Leo Tolstoy is a moving document of how a late 19th-century man dealt with the elusive meaning of life. Tolstoy suffers a major existential crisis in his late fifties, which brings him perilously close to suicide. His literary glory, worldly pleasures and the consolation of artistic ornamentation are of no use to him in a life that now seems empty and superficial. He studied the positive sciences with relish, but his silence on the fundamental questions, which he unforgettably formulated as follows, stopped him:

Study in infinite space the changes, infinite in time and complexity, of the particles, themselves infinite, and then you will understand your life.

As for the social sciences, if they were to speak, they would say: Study the life of all mankind, of which we can know neither the beginning nor the end, and of which we know not even a small part, and then you will understand your life.

He turns, then, to philosophy, the only one that could draw general conclusions from all this. But in its wisest exponents – Buddha, Solomon and Schopenhauer – he sees only the confirmation of his terrors: they all diagnose the same inanity and propose one method or another to escape from existence. But this raises a big question: why didn’t they commit suicide after their discovery? Why didn’t he commit suicide himself?

He was in this state when something drew his attention to the believers of the people, simple and illiterate men, pilgrims, monks, schismatics and peasants, who seem to have every reason to live. Unlike Buddha or Schopenhauer, who would propose a kind of ascetic elitism, Tolstoy already made clear in the prologue to War and Peace his sympathy for “the little ones”, his love for the wisdom of the humble. Intrigued by how they can endure much harsher living conditions than any philosopher or intellectual, he mingles with the great anonymous masses and discovers that they have the truth. The truth of faith.

Leo Tolstoy found the meaning of life in a sincere faith, but also one of convenience.

But Tolstoy cannot become a man of the people overnight, and he has plenty of intellectual leverage against the “superstition”, unacceptable to him, with which the ordinary believer inextricably combines his faith. He is martyred by not understanding the doctrinal dogmas he adheres to, such as the Holy Trinity, or the validity of the rites he observes. How often I envied the peasants for their illiteracy and lack of education. They saw nothing false in those postulates of faith which to me were nothing but plain nonsense. But it is the exclusivism of the various Christian Churches that most infuriates him; for someone like him, who has seen and read the world, these claims that all other confessions are false are little more than a provincialism of the spirit.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!