Inside, the first feature film by Vasilis Katsoupis, co-written with Ben Hopkins, premiered in the Panorama section of the 73rd Berlinale, is a tour de force by Willem Dafoe, the absolute protagonist throughout the 105′ film, in which he plays Nemo, an art thief who breaks into the penthouse of a multimillionaire architect. On his way out, he is trapped by a breakdown in the security system he had managed to bypass in order to steal several paintings by Egon Schiele, including a portrait that is nowhere in sight. As a man alone in a hostile environment who must fight for survival, Nemo —his name means “nobody” and is the same name Jules Verne gave to the protagonist of his adventure novels Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island— has illustrious predecessors in cinema.

However, Inside is intended to be more than just a story of resilience and perseverance, with its ups and downs, crises of faith in the possibilities of escape and more or less imaginative strategies for dealing with the stress of confinement. In this sense, Katsoupis’ original idea was also to provide a reflection on life and art, the meaning of artistic creation and its value in today’s society, without forgetting the wink at the risks of an integral automation of the everyday, by delegating to the “intelligence” of objects.

Thorsten Sabel‘s production design is striking, managing to portray the owner of the collection through the architecture of the brutalist-style house, in this way, the leaden concrete of the grand staircase, the huge windows and the skylight – whose dramatic importance will be decisive – frame and define a lifestyle and values that describe the owner of the house without us needing to know him or him to show himself.

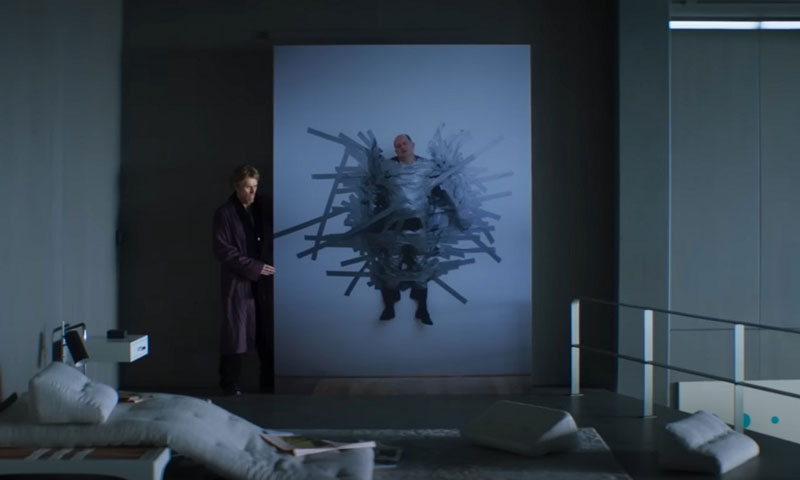

This habitat, photographed by Steve Annis —whose close-up shots of the stressed Nemo can even make one uncomfortable— will be characterised, of course, by a collection of contemporary art in all its media and supports, including a video installation by the Serbian artist Breda Beban, who was the director’s own teacher. From the enormous portrait that shows him with his daughter, it seems that even in his absence, the master of the house is present and defiant, exhibiting his power through a valuable collection, an overwhelming construction and an insulting economic power, without forgetting his profession, that literally projects and designs how others are going to live.

This portrait will also be the only work that Nemo vandalises during his confinement, with a childish stroke of mockery, defiance and irreverence, because this great absentee embodies one of the answers we least like to the great questions about the world and its banality, the ephemeral and the lasting, and above all about the function of art in our lives. Since the hunting scenes on cave walls, art has conjured up fears and encouraged desires, it has expressed emotions and ideas with an aesthetic will.

Nemo’s voiceover marks the film’s opening cue, as he enters the mansion and deftly turns off the alarm and locates his loot, recalling what he wrote in a school essay listing the three things he would save from a fire: my cat, an AC/DC CD and my sketchbook. However, he still recognises that there are two expendable: the cat dies, the music passes, but the art remains. And art is one of the tools that help him to resist, because transformed into money it is a means of life in society, but its expressive potential is unleashed in solitude, finding its true meaning. Transcending and being present even after death is a privilege of extravagant millionaires, who can resort to cryogenics or immortality by means of their replica in the form of a portrait or sculpture, and this is what the absent one exercises, who is also represented in a hyperrealist sculpture in the style of Maurizio Cattelan —at the ARCO art fair a recumbent Picasso by the artist Eugenio Merino has been shown, in the same spirit—, defying mortality and anticipating his departure from the building. In this grey-walled mausoleum, an artistic container that could serve as a burial chamber filled with treasures, Nemo watches the days go by in a short-circuited time, without water or food. Equipped only with a transmitter to communicate with his accomplice, he will also be cut off from the outside world, with no apparent possibility of escape.

However, the CCTV keeps him in contact with the second circle of connection within the building: the garage, the stairs, the lobby, where he discovers a young cleaning lady, whom he names Jasmine and fantasises about in his delirious confinement. The screens with black and white images then take on the characteristics of a new video installation, when Nemo’s gaze transforms them, endowing them with the capacity to generate emotions.

The crescendo of tension is not a paragon of originality, but it keeps us interested in the fate of the thief, never forgetting the sense of humour through symbols or discoveries, such as the “Macarena” that suddenly sounds when the fridge door is left open, or the transformation of objects by giving them a purpose different from the one for which they were designed. At no point does Inside disconnect us from Nemo’s travails, on the other hand, it allows the spectator to design his own journey through the adventure, remaining in the adventures of Robinson or abstracting his own reflections on this small universe, a cage of gold and glass whose progressive deterioration —it was filmed chronologically— is charged with meaning throughout the film.

Inside could have been a perfect vehicle for one of the great actors of his generation, if not the greatest, at least the one with the best tortured soul in cinema, capable of conveying a passionate vulnerability, a halo of harmless menace, with a voice, a gesture and a presence capable of contradictory and simultaneous expressions. Whether directed by Scorsese, von Trier or Ferrara, Willem Dafoe always steals the show, and in Inside, he is present in every frame, and even if we didn’t want to, we wouldn’t have been able to take our eyes off a recital that could sum up his entire career.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!