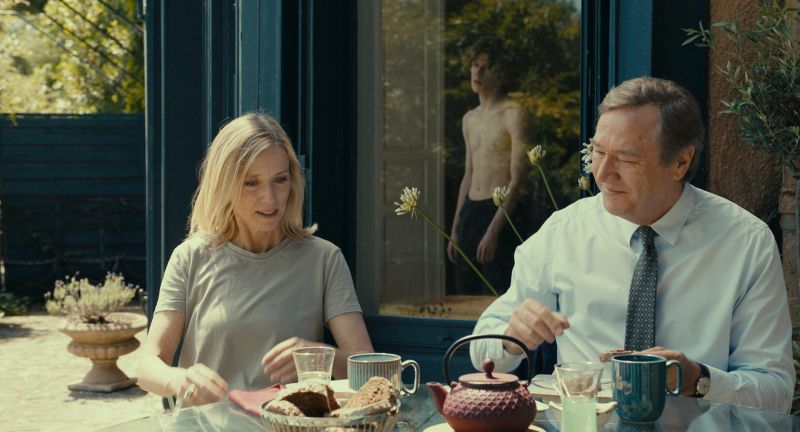

After its successful premiere at the 76th Cannes Film Festival, Catherine Breillat‘s new film, Last Summer, is now in cinemas. The name of this brave director, who at the age of twenty had already published the first of her novels, L’homme facile (1968), with which she earned her reputation as a transgressor, and who, together with her sister, took part in Last Tango in Paris (1972), began her career as a director by adapting one of her works, Une vraie jeune fille. Breillat, who knows no limits when questioning morality, adapted the Danish film Queen of Hearts (May el-Toukhy, 2019), which starred Trine Dyrholm, into her movie. The script of both films is practically identical, dealing with the story of a criminal lawyer, Anne (Léa Drucker), who has an affair that becomes complicated with her 17-year-old stepson, Théo (Samuel Kircher). As we mentioned in our review of the film, Breillat’s point of view, which focuses not on inappropriateness but on romance and the management of desire as it turns into feeling, makes this a unique film.

It is always a pleasure to talk to a creator who is not afraid of the headlines, so speaking with Catherine Breillat about her latest film and her vision of cinema and feminism was as subjugating as it was enlightening. Certainly, impassivity in the face of her words is never an option.

EVA PEYDRÓ: I believe the producer Saïd Ben Saïd owned the rights to Queen of Hearts and suggested that you direct Last Summer.

CATHERINE BREILLAT: Yes, and I think it was a brilliant intuition.

Indeed, it adds much to the original.

I think so too, that script, the whole mechanism of the lie… I think it’s perfectly in line with my cinema. Because, despite everything, for Anne’s husband to believe this lie means he wants to believe it. It’s still a question of denial and that has a lot of my cinema in it, and even the young boy (Théo, played by Samuel Kircher) has a lot of denial in his character.

Did your vision and the one of the producer differ in any way?

No, not at all, he let me do it. But the truth is that it took a long time. In France, nobody believed in me anymore, they thought I was too old…

There is an important chemistry between Drücker and Kircher.

Léa and I were incredibly lucky to find a replacement for the actor Paul Kircher. We had chosen him a year earlier, but at the time we started shooting, he was working on The Animal Kingdom and, on the other hand, he was already a year older, it’s difficult to match the age of a character, playing a 17-year-old who is then 19 and soon 20 is not the same. It’s crazy. He then told us about his younger brother, Samuel (they are both Irène Jacob‘s sons). The actor in the Danish film, Gustav Lindh, is too old.

The originality of his film lies in the point of view he takes on the love story of the stepmother and the young stepson, where the roles of victim and culprit are blurred.

I detest moralizing cinema. Cinema is an art. Neither writers nor filmmakers should moralize.

Finding a challenge to their prejudices or beliefs is an increasingly rare treasure for a good spectator.

Yes, without moral prejudice, it is a unique story. That’s why I left the ending very open.

Both versions of the film even have identical dialogue, and yet they seem very different. The reading of the story is different, here Anne does not appear as a predator. Although not much is offered about the character, we imagine her as a young woman who had to struggle hard to advance personally and professionally, and it is even hinted that she was a victim of abuse.

Yes, and that came up during the shooting. I created the film emotionally, because the Danish film, which is great, is not emotional at all. Mine was already a bit emotional in the writing process, but it was during the shooting that I got it. I ‘tortured’ Léa, because I wanted her to cry, but she told me that she cried too much and the effect was grotesque (laughs). I needed a single tear and I told her, No, it’s too soon, it’s not going to work. I wanted the tear in the other eye, because she had to bend down, you wouldn’t see her face and it would spoil the whole scene. She kept telling me it was impossible, but I told her we had all the time in the world for her to do it.

The ‘interview’ scene, with the two of them lying on the grass, humanizes her a lot.

Yes, she is formidable, she would have been very melodramatic with more crying. In that scene she is very good, she managed to do what I asked her to do, which was impossible. She needed that containment, and also there we realize that he acts almost as her protector, as a more adult, and that he loves her. These are things that can happen in life, just look at our president…

And she looks like a teenager, we see it in her eyes, and she seems to be getting younger.

Yes, because I asked her, above all, in that scene as in the one in the bar (which was shot earlier) not to think about anything and to be a Pauline at the Beach: You’re Pauline, you’re 15 years old and you’re with the most handsome guy in the class. He stands next to you and starts flirting with you. She did it like that and she instantly rejuvenated, she became a teenager, it’s something that cinema can do, it’s a privilege. It is said that the look is everything and that looking with love is something evident, Léa is radiant. And it’s the same with him, he becomes handsome the moment he falls in love with her. Before he looked more childish, with those chubby cheeks, he wasn’t so seductive.

At the end of the film, she acts like an adult, using all her resources, when she fears losing her position.

If she didn’t have experience as a criminal lawyer, she wouldn’t be able to lie like that. In the United States, you swear to tell the truth, but in France lying is customary. To lie to that extent and deny the evidence you have to have arrests… she is a great criminal lawyer.

Father and son represent two different models of masculinity, the son is idealistic, but in the end, it is he who wins.

The father prevails because he still loves his wife. The only thing he needs is for her not to confess because it would be unbearable for him. In the end, we know that he knows everything perfectly well, but that he doesn’t want to hear it.

Does his decision lie only in the love he feels or does he also do it to maintain the family situation, his status?

He wants to protect the family he has with Anne and their two young daughters, but also to keep his love. We see that this couple loves each other, even if there is no passion, passion destroys everything.

The way you film the sex scenes is remarkable, with close-ups of the faces, concentrating all the expressiveness there. I imagine it will be more difficult for the actors.

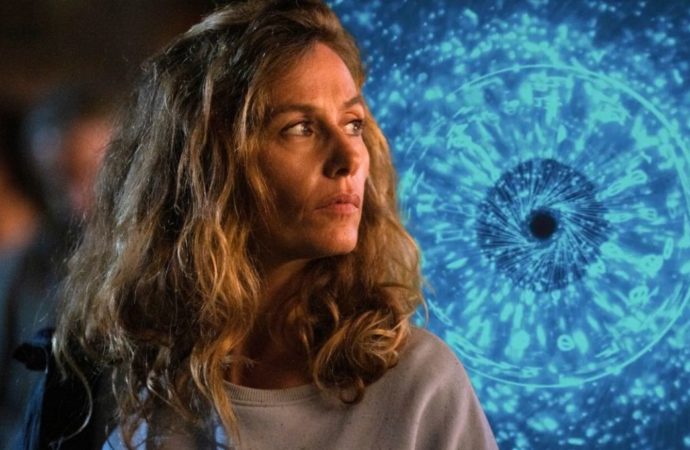

It’s very complicated, Léa Drucker repeated this a lot in interviews, she had never done a sex scene, she was like the girl next door, and doing it at 50 is more difficult than at 20. I told her that it was necessary to understand what was happening, but that I wasn’t interested in filming the body, because what happens when you make love is that you tell a story and you’re not always in the same state of mind. The first time they sleep together is not dramatic, it’s almost like sleeping with a friend, but then they make love, something different happens between them. In this film, there are four love scenes, and I told Léa that in each of them, the emotion and the love journey had to be completely different, otherwise they wouldn’t be of any interest. And where do you perceive it? It’s not in the bodies but in the face, it’s where we see the soul. I told him that I always end up with a close-up and that is much more intimate. Regarding the body, well, you get to the set, you take off your dressing gown and start your scene and all that, okay, it’s fine, we’ve got used to it, it’s work. We rehearse methodically, everything is simulated, but the ecstasy… actors can’t simulate emotions, they have to experience them. In all my films it’s like that. I get told a lot that I direct erotic films, but apart from those where the subject is sex, I only show faces.

How would you say she has evolved as a filmmaker? You have always been transgressive, but now you show subversion differently?

I have transformed this film into a love film. I told Saïd that I had betrayed him (laughs) because it wasn’t like that in the script. For example, in the scene where Paul goes to see Anne in her office, even though it is similar to the Danish film when he says he wants the father to know the truth, he is lying to himself, because what he wants is to have her. Saïd said no, but I told him it was a love scene between the two of them. I even advised him to re-read the classics. He doesn’t have that French culture, but to deal with love you have to reread Musset and Marivaux. Precisely, lovers lie. And they lie, to each other and themselves. They don’t want to admit that they are in love, but the spectator perceives it. We can see how he is on the verge of tears and that she cries, even if she is very, very hard, and stays hard, but with tears in her eyes, that is, it is a scene of love. It’s a textbook case: how do you transform a script into a scene? They are the same words, but the meaning is absolutely different, it’s about staging.

What visual references did you have in the film?

A lot of Caravaggio, for him, at the end, but also for Léa. In particular, the scene where he is between her legs, which ends with a close-up. If you superimpose it on the one of Mary Magdalene’s Ecstasy, it’s the same, it’s completely copied, because look, I realized it at night. I stayed on the set, I slept in the couple’s bed, and I kept imagining the scene. It was distressing because photographing a 50-year-old woman is not easy. When you tilt the head back, there’s a problem with the nose, because you don’t want the nostrils to look like a plug, and then there’s the neck, after a certain age, because you don’t want unflattering things. I refuse to let a woman be ugly. All of a sudden, I remembered Caravaggio and Mary Magdalene, because I wanted it to be an ecstasy. There is something sacred here, because love, and sex, have several functions, some trivial like fucking, which I have nothing against, it’s about pleasure. But, on the other hand, we have the loving function, which is ecstasy, it brings us closer to something sacred. So I went to check it out and oh, miracle! I had not long ago seen that painting, as well as The Ecstasy of St Teresa, in the exhibition at the Kunst Historisches Museum in Vienna Caravaggio & Bernini. In my memories, Mary Magdalene was a young woman, I look her up and see that she has the same nose as Léa. So I reconsidered the whole scene.

Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy (Caravaggio).

Sex is also political, if we talk about control and guilt.

Romance (1999), for example, is a search for sexual identity, for what it means to be a woman. We can’t deny that to be a woman is to have a woman’s body, so why in the name of that sex are certain professions forbidden to us, laws have been created so that we don’t have the same rights in the name of sex. It has always been a question of power, I say that testicles are not cerebral emissaries (laughs).

You say that you prefer actors to live emotions, not simulate them.

You can see that. In theatre you can simulate, but in film, when the camera gets close…

It is the same as Bernardo Bertolucci, reviled in the “woke” era, with whom his cinema has more than one point of contact.

My real teacher was Bernardo Bertolucci, although in France it was always thought that I belonged to the school of Pialat. Not at all. While I was on the set with Bertolucci, I watched him shoot, he had a genius at the camera, Vittorio Storaro. I have the Dolly, he had the Luma, so some movements were lighter and more complicated than what I can do. Last Tango in Paris (1972), in which I acted with my sister, is an immense film, and the previous one, The Conformist (1970) is marvelous. I have just seen it again with Samuel. I’ve loved Bertolucci’s films, and his style since I was very young. On the other hand, I’m not at all against the #MeToo movement, that’s a falsehood, on the contrary, I’m in favor of it. But I am against a handful of feminists, who have been caught up in this movement to convey a sectarian ideology that aims to destroy cinema and moralism, where we are all guilty. All directors and all scriptwriters are guilty.

But without freedom, there is no creation and no art.

I’ll tell you how the intimacy coordinators proceed. When they say they choreograph…, I choreograph. All the movements are made for emotion and the camera. They are insignificant gestures, there is no meaning. And then they say, hey, hey, these scenes, hey, we can have fun, but they have no meaning. The actors are acting, but they’re not having fun. It’s not like playing in a kindergarten. A love scene is an intimate scene, it’s a major scene, within a film. There is an important topic, we will remember this scene. And as an actor, it’s a job, it’s not a game, they get paid for it. Of course. And being afraid is normal. No, you shouldn’t have fun when you do an intimate scene. Yes, you have to be scared because it’s serious, there’s a gravity involved. You have stage fright, it’s the fact that you’re carrying something where you’re going to want to transcend yourself. So you’re scared, I’m scared too, I might do a failed scene, I’m terribly scared, the actors are scared too. If there’s only gesticulation, there’s no interest, they suddenly become erotic scenes. If there is no gravity, if there are no stakes, no emotion, it becomes eroticism and for me eroticism is immoral. I detest eroticism (laughs). I think of myself as an entomologist, if I film a praying mantis, which is going to eat its partner, once it has used him, then that will also give it the strength to procreate, that’s nature, I’m not going to judge the praying mantis. In the end, the survival of humanity depends on desire, and desire cannot be taken for granted, even if it can be tamed.

In my film, Anne sees no consequences in having an affair with Théo the first time, the problem comes when feelings add to desire. As they take flight, their story becomes beautiful, but also a risk of breaking up their family. Anne tells him several times that she doesn’t want to continue the relationship, and that she should forget about it, but as with the tattoo, in the end, she lets herself go. Consent is turbid. Rape is rape, and that is very clear, it is violent.

We miss so much real adult cinema that breaks away from conventions… Romance is a very important film in your filmography.

The shooting of Romance X was extremely pleasant, it was like a state of grace. But on the other hand, the young leading lady (Caroline Ducey) completely degenerated after the film. When we worked together she accepted everything, even if it wasn’t so obvious on the set. The thing is that she had a super-macho Iranian boyfriend and she wanted to leave him, so she thought that shooting the film would be the best way to break off the relationship. But, you know, editing and post-production take time, so in the meantime, she went back to him. So, something had to be plotted, I told her that there were two shots with Rocco (Siffredi), the first one was very raw, but in the second one you get more of the impression of them making love, you feel a purity as if he was giving his soul to her as if the beast was giving himself like a kind of King Kong surrendered to a tiny woman. I spent the whole night examining the two scenes and in the end, I decided to eliminate the pornographic one. It wasn’t a lack of courage, as I told Rocco, but to preserve the essence of the film. Besides, this way Caroline was not forced to confess to her boyfriend that she had slept with Rocco Siffredi.

Something similar to what happened in Last Tango in Paris.

Yes, it’s the same, and the directors can’t know it, but now I know it. It took me a while to realize it. I experienced something similar with Samuel, who fortunately didn’t have to shoot a scene like the one in Last Tango in Paris or Romance. The shooting of Last Summer was also a state of grace, he told me every day how he felt, and he was delighted (and his mother, Irène Jacob, too). Samuel was happy because he felt how he was progressing and also how he was maturing as a person, he felt that everything was going very well. But the problem is the post-film because there is this kind of postpartum depression. The film was phenomenal, the emotions were phenomenal, but all of a sudden you find yourself back in real life. We get bored, we feel abandoned, and we don’t know what to do. This happens to very young actors, who suddenly fall into the void. Samuel was lucky to have a strong family of actors, he had his parents and his brother by his side.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!