On October 5, it was ten years since the death of filmmaker, writer, and visual artist Chantal Akerman (Brussels, 1950 – Paris, 2015), one of the most essential figures in cinema of the past fifty years. Her work has influenced directors such as José Luis Guerín, Sofia Coppola, Greta Gerwig, Céline Sciamma, Carla Simón, Alauda Ruiz de Azúa, and Todd Haynes, among many others.

Initially confined to avant-garde circuits, her name began to resonate with wider audiences in 2022, when Sight & Sound magazine named her film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) the greatest film of all time. Since 1952, every ten years, this prestigious magazine, published by the British Film Institute, surveys critics worldwide to determine the ten best films of all time. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948) topped the list in 1952. For fifty years, the number one spot was held by Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), until Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958) displaced it in 2013. Akerman’s film in turn, overtook Vertigo, a choice that stirred debate given its experimental and feminist nature—far from the canon that had dominated previous editions.

Without fanfare or major media support, Chantal Akerman’s reputation has steadily grown over the years through the strength of her work. This reappraisal owes much to Sight & Sound’s selection, as well as to the invaluable work of the Chantal Akerman Foundation, established in 2017 in Brussels, in collaboration with the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique. Together, they have ensured her work is studied, restored, and exhibited in international film festivals, cinematheques, digital platforms, and contemporary art museums around the world. Recent retrospectives at venues such as BFI Southbank in London, MAC/CCB Museu de Arte Contemporânea in Lisbon, the Melbourne International Film Festival, Institut Français Barcelona, and MoMA in New York, speak to her enduring influence.

A descendant of a Polish-Jewish family, Akerman’s passion for cinema began at fifteen, after watching Pierrot le fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965). In 1967, she enrolled at the Institut National Supérieur des Arts du Spectacle in Brussels, but dropped out after a few months. A year later, she self-financed and shot her first short, Saute ma ville—a model she would follow throughout her career.

In the early 1970s, she moved to New York, where she discovered the experimental cinema of Jonas Mekas and Michael Snow, beginning a lifelong collaboration with photographer and filmmaker Babette Mangolte, who would sign the cinematography of many of her key works. In New York, Akerman made La Chambre and Hotel Monterey. Upon returning to Belgium, she directed Je tu il elle, one of her most iconic films, in which she starred herself, followed by Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, presented at Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight in 1975 and described by The New York Times as the first masterpiece of feminist cinema.

Jeanne Dielman is a hypnotic experiment that crystallizes Akerman’s creative freedom and radical aesthetic. Drawing from both American avant-gardes (Mekas, Snow, Warhol) and European modernism (Bresson, Dreyer, Godard), Akerman builds a filmic structure that masterfully uses long takes, usually with a fixed camera, defined by gesture and duration, punctuated by off-screen movement and lateral tracking shots. With these simple elements, she narrates the banal and invisible: the monotonous fragments of a widowed woman’s life (magnificently played by Delphine Seyrig), mother to a teenage son and occasional sex worker. Out of this banality emerges a buried violence, shattering the patriarchal invisibility of women. Akerman’s film is ethically charged: her images refuse to remain merely iconic, becoming iconoclastic artifacts—an “iconicity of iconoclasm,” both subjective and ethical. Some have called Akerman’s cinema iconophobic—and they would not be wrong.

Blurring the line between fiction (Tout une nuit, 1982; Les rendez-vous d’Anna, 1998) and non-fiction (Hotel Monterey, 1973; D’Est, 1983; Histoires d’Amérique, 1984), Akerman crafts a minimalist and hyperrealist gaze on the everyday—on empty streets, metro stations, hotels, and domestic spaces. Her entomological eye examines the invisible; her work is, in the Levinasian sense, a reflection on the Other that ultimately becomes a reflection on herself. Through this personal alterity, Akerman interrogates identity, emotion, human relationships, the impossibility of love, and solitude. Time, for her, is a rhetoric of mesmerizing monotony—repetitive, musical, and silent—transforming the real into poetic intensity.

The kitchen stands at the core of this exploration of self, from Saute ma ville to Jeanne Dielman and finally No Home Movie (2015), her cinematic testament and an intimate love letter to her mother, Natalia Akerman, an Auschwitz survivor. This nurturing, umbilical space becomes both personal and mythic—Akerman’s Ithaca, a place of departure and return. No Home Movie closes one of the freest, most coherent, and most feminist filmographies of the past fifty years. The film opens with a long take of a tree swaying in the wind—silent, resilient, and almost imperceptible, like life itself. Soon after filming ended, Natalia Akerman died. A few months later, on October 5, 2015, Chantal Akerman took her own life in Paris. She was 65.

I do not want to end this article without briefly mentioning Akerman’s artistic and literary work. Her films are the starting point for her video installations, in which she continues to reflect on time and space, the family atmosphere, the boundary between fiction and non-fiction, and the invisible everyday. The fixed shot as a poetic device and as an interrogative register. The artist began to take an interest in this language in 1995 with From the East: Bordering on Fiction, developed through the re-reading of her film D’Est with her editor and collaborator Claire Atherton. After this piece, Akerman created fifteen more video installations.

From the East: Bordering on Fiction.

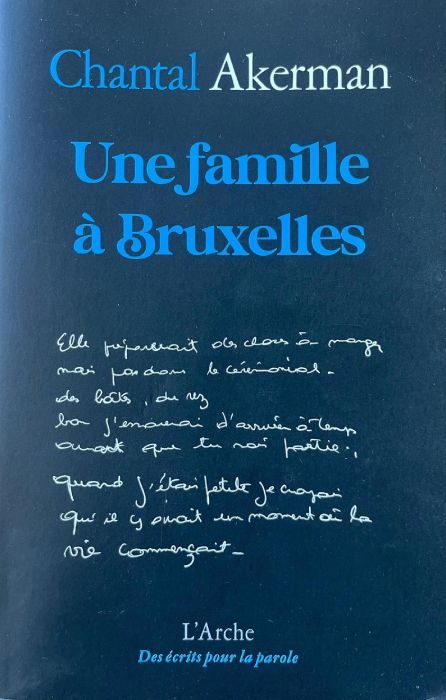

Translated into several languages but still unknown to most readers, the literary work of this filmmaker is inseparable from her filmography and the rest of her artistic production. Her books are a transposition of visual images into textual ones, part of her ongoing exploration of lived time. Among her essays, I would highlight two works that I consider fundamental—both autobiographical in nature, with the figure of her mother as their central axis. Two minimalist works, innovative in both form and substance, remarkably evocative and of outstanding literary quality: A Family in Brussels and My Mother Laughs.

The first, published in French in 1998 and translated into several languages, is a narrative about grief and solitude. It is an impressionistic portrait of a woman who has just lost her husband, living alone in her Brussels apartment, speaking on the phone with her daughters. A tapestry-like text, with phrases that stitch together stories, emotions, and feelings. As in her cinema, A Family in Brussels is an ode to that nothingness which is, in fact, everything.

For its part, My Mother Laughs, first published in 2013, has appeared in several French editions, including a 2021 Gallimard edition that marked its international revival, as well as translations into English, Polish, and Spanish. This final text written by Akerman before her death is a minimalist introspection on home, family, illness, and death. Like No Home Movie, it is a twilight work that becomes a literary testament, born from a meditation on the construction—or non-construction—of the self.

“I can only bear it if I write,” Chantal tells us. “My life, I have no life. I wouldn’t know how to build one. So here or there. But elsewhere is always better. So I leave and return, I always return.” Departures and returns, the search for the need to exist, to build while knowing one does not know how to build, to live while not knowing how to live—but always in freedom. Great Akerman.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!