In 1985, 40 years after the painful and fierce victory over Hitler, the Soviet government commissioned Elem Klimov to make a film in the service of the patriotic war, a kind of prayer to the millions of fallen (in the genre inaugurated by Pericles), a story about the heroic struggle of the Russian people against the evil embodied by Nazism. The result was too harsh even for the producers. Come and See not only told a powerful story (the catastrophe of Nazism in the eyes of a child) but did so with a sweeping synthesis of the formal resources of the cinematic language of the best avant-garde films of the 1920s to achieve one of the most disturbing films in the history of cinema.

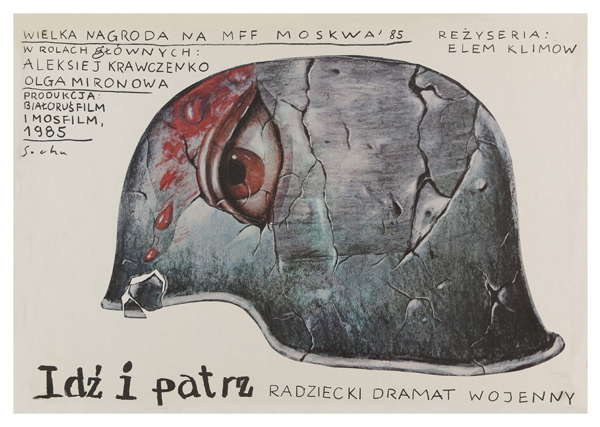

Of all that has been written about Klimov’s film, I would like to insist that Come and See is basically about the devastation of a way of seeing the world. That is, its formal and argumental core takes place in the gaze (of the protagonist and of the spectator), and in particular in the bloodshot eyes of Floyra, the child played superbly by Alexei Kravchenko.

Idi smotri begins with the threats of an adult to some children digging in the sand: sons of bitches, scavengers, I’ll give you what you deserve, words soon imitated by the little ones in a scene full of symbols (the inverted game, the weapons of the dead as treasure) and which links, as it were with J. L. Austin‘s title, with the different forms that the film takes on in the film. Austin’s title, with the various ways in which words do things: the recruitment of the young boy seduced by the patriotic speech, the mother’s tears, the threatening appearance of German soldiers falling from the sky as a curse of nature, the need to stifle laughter as a rupture of innocent and sensual games with a simple girl whose vulnerability will soon be sniffed out by the Nazi beast.

If one retains the young beardless boy’s initial smile and compares it to the ravages of the face in the hellish final stretch, one will perceive not so much a revival of Soviet expressionist acting techniques, but a terrible series of metaphysical shocks from the century of horror. Floyra’s expressive eyes forced to go and look reflect the same state of shock with which the spectator leaves the darkness of the room to enter the real world.

As much as we see nothing in the first and see everything in the second, the two main massacres of the film are equally terrifying because of the masterful ways of understanding the editing: the extraordinary psychoanalytical and metaphorical play with the broken dolls in the child’s old home —the motley symbolism of the Soviet school— the bodies piled up in the background of a peculiar depth of field with the naturalness with which a bale of hay is piled on the ground.

And on the second – the massacre that we are already obliged to watch – the impact on the spectator results from a synthesis between three findings of Russian cinematography: on the one hand, the striking clash of shots of Sergei M. Eisenstein‘s “fist cinema” (and Kozintev’s FEKS/Factory of the Eccentric Actor); on the other —the less contrived—, almost documentary-like “eye cinema” of Dziga Vertov; finally, the lyricism, decades later, of the great master Tarkovsky.

What would they have thought, how would Theodor Adorno or Walter Benjamin have reconsidered their prejudices about cinema, if, looking into the future —just as Angelus Novus looks in turn into the horror of history, into catastrophe upon catastrophe— they had come to see how the communication of the unspeakable horror of their alienated century resorts to the formal peaks of the avant-garde of 20th century art in order to be effective? Such is the select perfection of the framing, the crackling use of sound, the scenes devoid of dialogue, the peculiar realism, the colour ablaze with flames: scenes for an anthology of visual language: the children swimming in the mud, unable to get out, that is, unable to forget what they have just watched.

And the same will happen to the spectator, because what we see in Come and See are episodes of sadism that was real. It is typically Nazi barbarism, not only because it was carried out by the extermination battalions led by the SS in Operation Barbarossa, but also because of the grotesque, circus-like elements, the delectation and objectification of the subject: the rape, torture and slaughter of the most defenceless and vulnerable beings (peasants, old women, children). That is, as much as the film is aware of sharing the classic resources of a cinema suitable for political propaganda (searching for the emotional reaction of the audience, rhythmic editing scenes —duration of the shots in accordance with the musical rhythm— tonal and intellectual tension), the truth is that the reality of the horror surpasses the propaganda.

Come and See is the reverse of what Karl Morgenstern and Wilhelm Dilthey coined as the Bildungsroman, a novel of education: it is a story of destruction. First of innocence, then of trust in the world. The dramatic charge, in a kind of transference of evil (in the manner of the portrait of Dorian Gray) onto the face of the beardless child, expresses both the extreme harshness and the extreme poetry of cinema.

Come and See is being screened again in cinemas in collaboration with Filmin (the fictional saviour of the pandemic). I left the Cinematheque like anyone else who sees the film, in a state of shock, full of fury and the desire to join the Red Army.

Those who go and watch will dream of skulls and Hitler’s effigy on the Belarussian plain, another visual find; the young girl with the musical wind instrument embedded in her mouth and her legs covered in blood will appear to them from time to time, they will rethink anthropology (I know of no film that is a greater catastrophe for Lockean and Rousseauian do-gooderism), they will rethink equidistance; I do not agree that the later Russian revenge on some of the slaughterers is of the same nature as the Nazi one: the Russian militia corps retains piety. The hatred for the Nazi is not because of who he is, but because of what he has done: an ethical success of the screenplay adapting Alés Adamóvich.

Beautiful: resources of Russian cinematic language.

Damned: liberal permissiveness with Nazi denialism.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!