It seems risky to say it, but from here we maintain that weird Uncle Bob, who is turning eighty, is the most important composer that popular music has produced in the last century. Not the best lyricist or the best poet (increasingly frequent exaggerations in mainstream culture), but a composer of melodies and chords. This is not to say that he is the one we listen to the most, or even enjoy the most, although when we do enjoy him it is in a very peculiar way. In an imaginary podium of favourite musicians, no doubt we would place him below the first triad, and yet he is a better composer than all of them. How can this be explained?

Let’s start by saying that Bob Dylan holds the record for songs that seem mediocre until others cover them. For example, in our early days we missed a song called “My Back Pages” at every turn of Another Side… until we heard it from the Byrds. Now it’s the one we like best on that bittersweet album. And it’s not our doing: some of his best-known tracks (“Blowin’ in the Wind”, “Mr. Tambourine Man”) only became official hits when others lent him a hand. It wasn’t until 2020 that a performance of his reached number one. What is it about his songs that they start selling when a third party simply covers them? Or perhaps, what is it about him that doesn’t keep our attention for a long time? The reverse is also true, and as a result we have suffered for decades from the dogma that covering a Dylan song (which after all can be anything in its minimalism) is a guaranteed hit, especially if it’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”. We have also long been under the bias that a “Bob Dylan” song is good in itself (Dylan himself has been one of those who have abused this). The big question is: why are they so fickle?

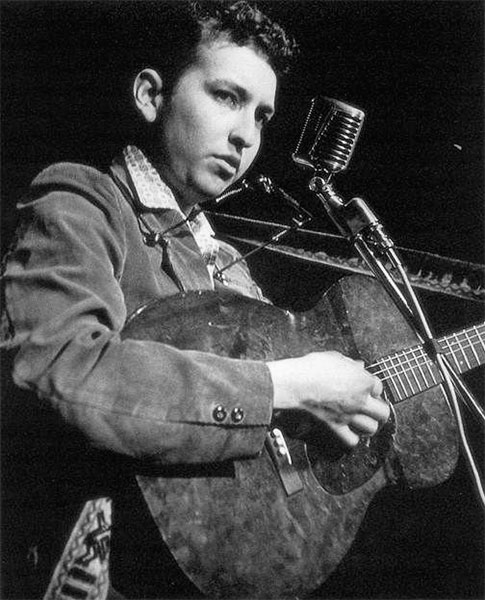

He was voluble in character, but above all he was prolific, and the texts that accompany some of his songs from the golden age between 1963 and 1967 are among the most beautiful of his decade. They wield the exotic cologne of the Beat and, at the same time, the sand-stained trousers of the Midwest. It is a candle the size of a sun for that generation that began the adventure from the farthest reaches to reach the most intimate. In the case of Dylan’s (psychedelic) old-fashioned taste, deep America. And yes, he made a lot of songs, but he also insisted on slipping in blues and dreamy filler even at his peaks, and even if his tidy genius was genuine, so what? To say “he was a genius” means nothing. Many of the great artists did only one or a very few works and then devoted themselves to the dignified craft of living, which, as Sábato explained, is no small thing.

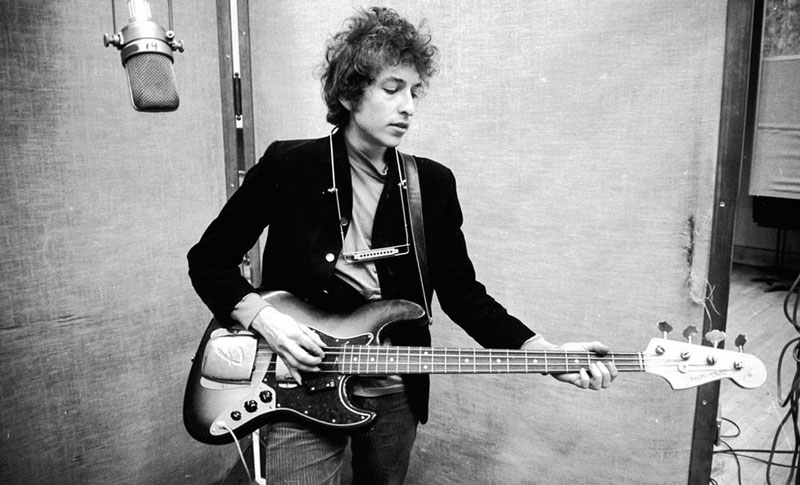

As we were saying, Dylan has been insisting since the seventies on the song model that made him so famous, sometimes with notorious results and sometimes not so much; revealing, in any case, his way of approaching songwriting: just spin the four chords and see what comes out. For his most wonderful tunes usually consist of the same chords, sometimes in almost the same order (see “Girl from the North Country”/”Boots of Spanish Leather”), no revelation. So much has been said about the sincerity of the committed poetry of his early period, in which he was blithely heard to claim that he wrote what people wanted to hear, while we overlooked his trick of conjuring up a few chords and superimposing on them a melody with calculatingly effective hooks and turns. Does this approach to creation exclude feeling? It’s as impossible to measure and absurd to discuss as the other, but at least it sounds a little more original.

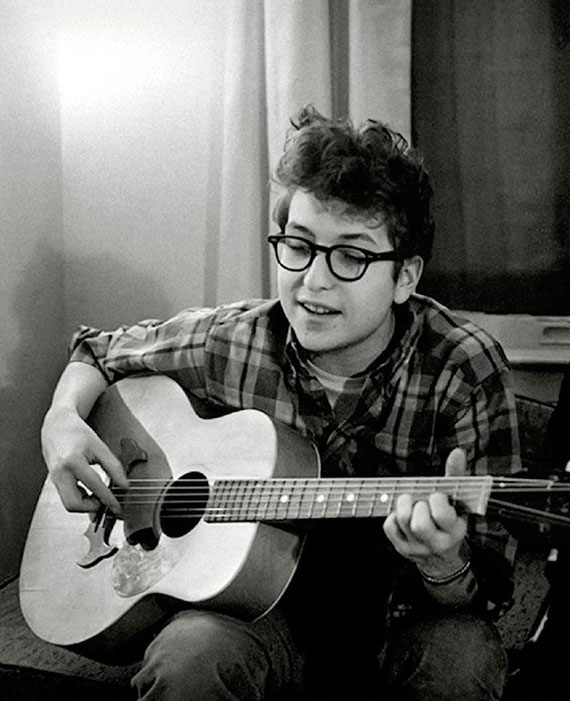

And let’s not talk about his voice of “sand and glue”, as another slippery fish described it. Today it is a marker of classicism, but could anyone argue, when he started out, that the boy had a privileged voice? And, even if one could enjoy it, did he sing well? His imperfection was noticeable, he could go off-key in live performances and even lose his rhythm. As amateur harmonica players we can attest that some of those hair-raising melodies consist of a random breathing in and out through the holes, which is not out of place thanks to the absence of any tonal complexity in the song structure.

Nor is he an artist we enjoy listening to for too long. A long time without Dylan tends to generate a kind of longing that is satisfied from time to time, but let’s see who’s the smart one who can last a whole month listening to him non-stop. A fanatical folkie like the ones who would mutilate his electric guitar with an axe. Or worse, those who automatically place any artist’s senescence slime among the best of their history. And it’s not because of the nakedness of the performance, because with others we can get months locked up as long as there’s a guitar and songs and a room.

Dylan knew what foundations were needed to move anyone, that is, the foundations of American and Irish folk, country, blues, black spirituality… He knew them more than well, which is why his list of songs “inspired” by other people’s compositions is quite extensive. His second album, one of his most complete, has few songs that are still free of the suspicion of this game of references.

We have therefore come to the conclusion that the Dylan who conquered the world was an average performer, a songwriter who went for the easy way – although he managed to hide it well: one of the accompanists on the Highway 61 Revisited sessions claimed that he was the man with the most chords in his hat of all those he had met – and a rogue in his choice of themes and melodies. And yet…

Nevertheless…

And in that “however” is contained the answer. In their version of “All Along the Watchtower”, U2 added: All I have is a red guitar, three chords and the truth. We already know that it has three chords, enough to move us simple-minded, blockbuster-loving children, but what truth is that?

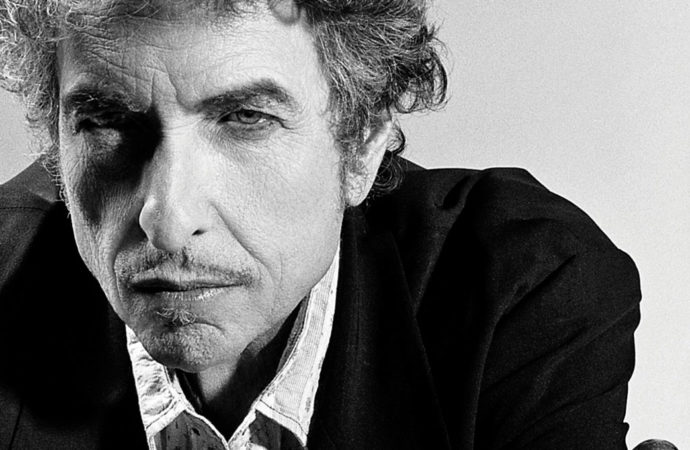

It is public and notorious that, however much you combine those three chords, you will hardly come up with something memorable, and never something that sounds so young and so old, that it could be from the sixties or from centuries ago. Even Dylan himself couldn’t do it in anything but exceptional ways. It’s just that those exceptional forms were concentrated in a small number of years (almost 20 months, the bulk). Not so long ago he declared in an interview that whatever possessed him then had long since gone, a completely atypical statement for someone who boasted of having shared blues with legends he never crossed paths with and of having lived a life so extraordinary that it would take a film featuring six actors to do it justice.

Et pourtant… Dylan shows us that the minimum is the maximum. That the impossible to imitate is not the intricate, because the intricate follows an (intricate) logic and this can be understood. That from these muds these muds, but from these stinking muds this clear water. And that even the most sui generis voice can sprout a captivating melody. And, unlike those who pretended to be rebels or philanthropists, he ended up proving that he was not afraid of anything. Few people are so widely and so little known. But it doesn’t matter, the music is there for anyone who wants to hear it.

He was an impostor, yes. His music is a farce, yes. Do, we insist, the 48-hour-Dylan test if you haven’t already done it, and you will see that his originality and variety diminish to the point of almost disappearing. Whether or not he was “serious” about what he was doing, we will never know. But few have succeeded so well in highlighting that all art is a farce by making great art, classicist, timeless, and not Dada. And even more so in music, whose mathematics is much more evident than that of a novel. And, within music, even more so in the popular music of this century, whose sums don’t even have decimals. It always pretends to want to change the world but in reality it does it to get drugs, power, money, women. It is a veil that no one has lifted as abruptly as he has. Specifically, it happened on 25 July 1965.

Don’t get us wrong. We love his voice, we love his harmonica solos, but that does not detract from the fact that we consider them technically flawed. It is precisely in this inadequacy to the categories that serve for others that his charm lies, that makes him the greatest composer of the 20th century. It only happens when we like something because of an irresistible something that only we find irresistible. Bob Dylan is the universalisation of that feeling. He is, therefore, an intersubjective consensus. This is no small truth, in these times we live in.

This is what that “however” shows us, but not what Dylan is. What he is, the soul, the Spirit, the Ba, the Ātman, the Nafs, the Hun and Po, you will not find in this article, let alone in his music.

And what a pity about those who pretend that theirs are!

So much in so little!

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!