In an edition with memorable premieres, the most anticipated of the films released at the 79th Venice Film Festival was Blonde, directed by Andrew Dominik and starring Ana de Armas. Watching the Cuban actress transform into the most famous blonde in history was the biggest hype factor. More than a dozen actresses had tackled that impersonation before, from caricaturing the most prominent features of the character —Madonna or Blake Lively imitating her in her adoration of diamonds— to the most intimate side of the person (or what we intuit of her) —Michelle Williams in My Week with Marilyn (Simon Curtis, 2011). She was even split into two performers in the TV movie Norma Jeane and Marilyn (Tim Fiwell, 1996), in which Mira Sorvino and Ashley Judd play the biography of a beleaguered actress with whom, in the light of the Weinstein scandal, we imagine it would not be difficult for them to empathize.

Curiosity about the style with which she would deal with such a character, steeped in the popular imagination for almost a hundred years, was understandable and has been more than compensated for. The film, produced by Plan B —a new collaboration between Brad Pitt and Dominik distributed by Netflix— is based on the novel of the same title by Joyce Carol Oates, from which the director wrote the screenplay. Fourteen years of preparation and production were necessary to bring before our eyes a spectacle that deserved almost every minute of its prolonged genesis.

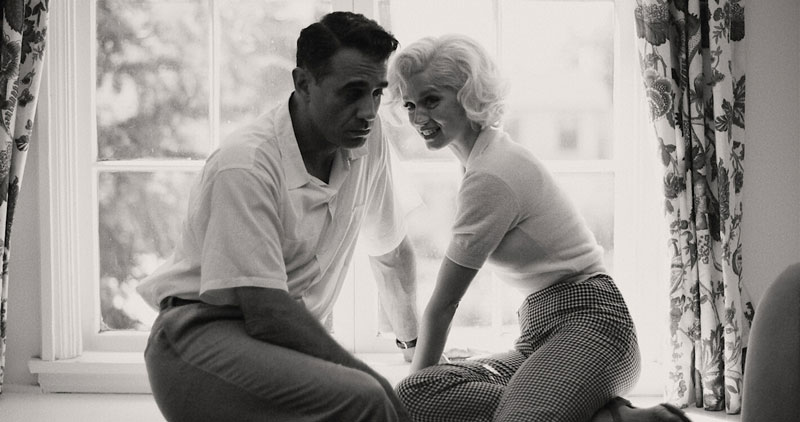

As for Ana de Armas, it could be enough to mention just one image from Some Like It Hot (1959) to confuse us between a real image and a recreation, such is the fidelity with which the actress has incarnated the myth, relying on a whole battery of physical resources, make-up, hours of study, an amazing command of diction in someone who didn’t speak English five years ago, and, according to Dominik, an astonishing intuition above and beyond the aforementioned. When we speak of the protagonist of Niagara we speak of myth, because it is the first level on which anyone has met Marilyn, who does not even need a surname to be identified, we access the person in the meaning of classical theatre, that is to say, the character who here, in turn, plays other fictional beings. Marilyn is a constructed symbol (especially sexual) that represents a set of collective longings, desires, aspirations, and fantasies, of men and women, that coagulate in a single being, chosen and prepared as a recipient of our need to mythologize. In her, the intimate need for acceptance was united with the studio’s need to transform her into a star at any cost, and that price was to widen the gap between her real personality and her character, between Norma Jeane and Marilyn Monroe.

In Blonde we find an actress, Ana de Armas, convincingly impersonating a woman with a certain personality, once an icon, a sign that we can easily read and understand. The story of how Marilyn came to be that —and the cost it entailed for someone who started out with a very deep wound that made her theoretically the worst candidate to bear such schizoid pressure— was novelised by Joyce Carol Oates without sticking entirely to the real facts, without citing names, referring to the characters by their profession, thus distancing us from the glare of the couché to objectify a process of destruction and self-destruction that is textbook, scalable and universal. Through Blonde parade a mentally broken mother, two husbands – as diametrically opposed as their public and private selves -, the president, directors with whom she worked, protectors…, with whom she deals with by lowering her self-esteem one step after another and increasing her pathological insecurity.

In the creation of the myth, overvalued qualities, which the person does not have, are attached to transform her into a character of overwhelming strength and inextinguishable appeal. In Blonde, Andrew Dominik focuses on Marilyn’s identity crisis throughout her wretched existence, in which she ceaselessly sought to please, was submissive and yearned until her last day for a daddy to fill a vacant position for as long as she could remember. The film’s overture is already a chilling account of experiences whose impact on the future actress would be decisive in her destiny, whose disorder so many psychiatrists, lovers, husbands, counsellors, acting teachers and producers or directors who surrounded her and took advantage of her vulnerability in one way or another were unable, unwilling or misunderstood to deal with successfully. The whole film is contained in these first scenes and its development is a via crucis of sometimes unbearable contrast.

This abysmal gap that separates Norma Jeane and Marilyn acquires depth as the years go by, because the greater the need for acceptance, the greater the desire to please, the less value is placed on the aspects that distance her from the archetype, from the collective fantasy, which in the middle of the last century could not conceive that an intelligent, sensitive, creative and politically aware actress could be both the most beautiful and most desired woman on the planet.

And how do Andrew Dominik and Ana de Armas depict it in Blonde? in a dazzlingly visual proposal that alternates black and white and colour, without pretending to narrate a typical biopic -in fact, the novel on which it is based is not a biography-, or to make us believe at face value that what we see was real. What the director is trying to do is to create a sense of intimacy with a barrage of scenes in which the facts are less important than the emotions they provoke, because the emotions were already there before, just waiting to be unleashed. If you want a biopic you should read Donald Spotto‘s magnificent biography, an extremely well-documented work that goes so far as to detail the circumstances of the actress’s death, based on a well-articulated hypothesis, but if you watch Blonde, you can be sure that the most interesting aspects of Marilyn’s life will be conveyed to you on an experiential level.

You will think you know her, you will understand her, you will know what made her happy and, powerless, you will see her descend into hell without being able to lend her that hand that she was always denied or did not know how to give. Perhaps too many interests surrounding the goose that lays the golden eggs and too little real empathy to know who she really was, because whoever had ascendancy over her took advantage of it to manipulate her. Ana de Armas reveals in her candid look a tremendous need, a hunger of years that plunges her character into depression, dissatisfaction, which she shows with a performance built with nuances and small gestures, with which she moves between the two characters, Norma Jeane and Marilyn, with impeccable naturalness.

Adrien Brody and Bobby Cannavale play Arthur Miller and Joe DiMaggio with respect for the character, although both are overshadowed by their partner, while Julianne Nicholson, as Marilyn’s mother, scares us to the bone; the music by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis is effective to make us surrender to the director’s demands. He entrusts the photography to music and fashion video specialist Chayse Irvin and editor Adam Robinson, with the same experience, the editing, so that this cataract of images and scenes reaches our senses before it reaches our minds. At times, this exuberance can overwhelm the spectator, or become tiring, but nothing could be further from a Bazz Luhrman and his Elvis, because here there is no mannerism or posturing or mystification, the mythical nature of the character himself is enough and to spare. Ana de Armas’s nudes are pure, transmitting freedom, integrity, and the sex scenes are crude in their lack of consent and spontaneously joyful in those of total surrender, where we see Marilyn liberated from the need to seduce an audience that she does not see on the other side of the screen or a producer to help her climb a step up the ladder. The scenes of the lively threesome she forms with the children of Charlie Chaplin (Xavier Samuel) and Edward G. Robinson (Garret Dillahunt) show not depravity but joy, complicity and perhaps happiness, on one of the few occasions when the chain of suffering gives us a truce.

The contrast of glamour and despair, emotional destitution, beauty and insecurity, black and white and colour, public and private life, reality and desire, spares no crudity, far from the lurid portrait one might expect, because this is the Marilyn of the 21st century, the one that Andrew Dominik brings out of the underworld to exorcise her spirit through a Latina actress who has understood it with her own skin.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!