It is often said, and I think with good reason, that John Hughes‘ films knew how to capture the angst of the youth of the 80s and accurately describe their concerns, their obsessions, their way of understanding life. I don’t get the impression, however, that so much has been said about how Martin Scorsese captured in After Hours (1985) the concerns of the average American, channeling them into a film as delirious as it is dramatic. A film that has received a 4K remastering, presented at the last Berlin Film Festival, thanks to which it looks even more spectacular, if possible, than it already did.

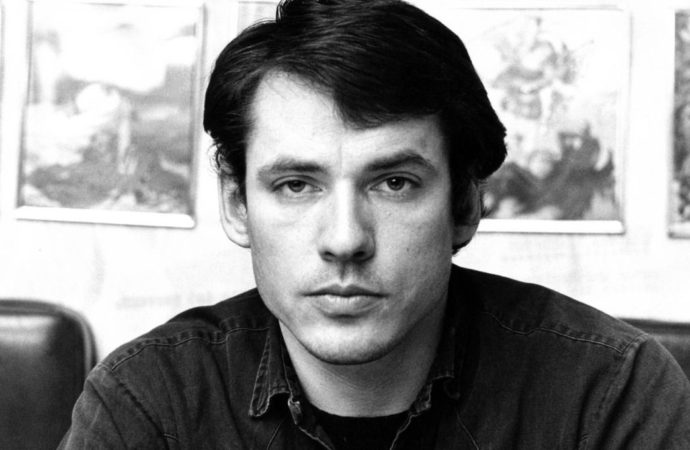

The genesis of this film is well known: Scorsese was coming out of the personal setback caused by Paramount’s last-minute cancellation of his beloved project The Last Temptation of Christ (which he finally managed to shoot in 1988) and needed to shoot something quick and easy. Griffin Dunne and Amy Robinson, producers who already had some previous success, had in their hands the script of Joseph Minion, which they had initially assigned to a director who had not yet directed any film and who answered to the name of Tim Burton. But the script fell into Scorsese’s hands, he loved it, and when Burton found out he decided to step aside from the project in a gesture of courtesy and respect that honors him.

The story of After Hours is really curious: Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), an ordinary New Yorker who makes a living as a data processor, finishes a routine day’s work and decides to dine out. At the restaurant he meets Marcy (Rosanna Arquette), an attractive woman with whom he ends up meeting at the apartment she shares with sculptor Kiki (Linda Fiorentino). From then on, a series of unexpected events unfolds that test Hackett’s resilience and his determination to go home to sleep before returning to work the next day.

To begin with, it is surprising how foreign material ends up fitting so admirably into Scorsese’s cinematic universe. For example, the concept of sin and atonement that, without being explicitly mentioned, can be read behind Hackett’s misadventures: obviously, the whole night starts because the protagonist has seen in Marcy a clear possibility to get laid, and in fact that is what he tries to do at one point of the night. Everything goes wrong from that moment on, and Hackett’s frustrated sexual adventure leads to his desperate attempt to return home. But the more he tries, the more bizarre characters he encounters and the more difficulties stand in his way: everything that happens to him, then, can be understood as a divine punishment for having given free rein to his sexual instincts.

Sin, guilt, punishment are themes that have been the backbone of Scorsese’s filmography since his beginnings and that appear, sometimes explicitly and sometimes more subtly, in many of his films. After Hours is not only no exception, but, in fact, materializes the premonitory phrase that can be heard in one of Scorsese’s first films, Mean Streets (1973): “Sins are not redeemed in church, they are redeemed in the streets”.

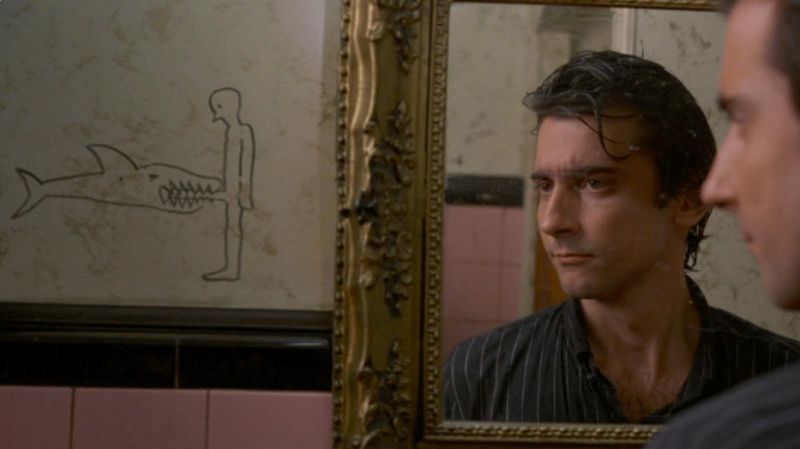

Esa variopinta galería de personajes con los que se encuentra Hackett en el transcurso de una sola noche es donde, seguramente, reside el alma del absurdo retrato que Scorsese dibuja de la noche del Nueva York de los años 80. La posición del protagonista ante todos ellos es casi siempre de perplejidad, lo que alimenta esa visión absurda. Y aquí es clave la presencia de Griffin Dunne quien, con una extraordinaria ductilidad en su rostro, es capaz de transmitir toda esa perplejidad en uno de los one man shows cinematográficos más hilarantes que recuerdo.

That motley gallery of characters that Hackett meets in the course of a single night is where, surely, lies the soul of the absurd portrait that Scorsese draws of the New York night of the 80’s. The protagonist’s position before all of them is almost always one of perplexity, which feeds this absurd vision. And here the presence of Griffin Dunne is key, who, with an extraordinary ductility in his face, is able to transmit all that perplexity in one of the most hilarious cinematic one man shows I remember.

Right off the start, Hackett doesn’t quite understand that a beautiful woman like Marcy is willing to make a move to get close to a man she doesn’t know at all. Disbelief is plastered on his face throughout the restaurant scene. Then there is the work of Kiki, who makes plaster sculptures covered with newspaper: again, Hackett’s gaze reveals a certain surprise, as if he doesn’t quite believe (or understand) that this could be art.

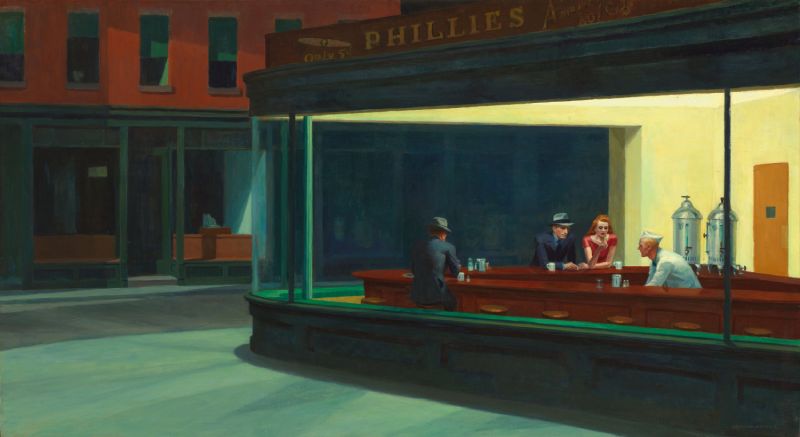

Nighthawks (Edward Hopper, 1942).

That expressive Griffin Dunne face continues to project inner stupefaction in almost every encounter that follows in the evening. For example, when he goes to Julie’s house, the waitress desperate to find a Prince Charming to rescue her from her dull existence (delightful Teri Garr), a character that synthesizes one of the ideas that vertebrates the whole film: Hackett, Marcy, Julie, all are the nighthawks portrayed by Edward Hopper in his famous painting Nighthawks, nocturnal and lonely souls in search of affection, of human warmth, in search of the contact that Peter Gabriel described in 1982 in his sublime song I Have the Touch. In fact, the quotation to Hopper is more or less explicit in that night café, the River Diner, where Marcy and Hackett take refuge to get to know each other.

Disbelief on Dunne’s face again, in this case already transformed into rage, when he meets Gail (a no less splendid Catherine O’Hara), the nutcase who ends up organizing a citizen’s raid to arrest Hackett believing that he is responsible for the robberies that plague the neighborhood. Perhaps there isn’t much surprise at the beginning of the encounter, but the unpredictable soon hits Hackett in the face again when, trying to memorize a phone number, Gail prevents him by reciting random numbers to betray his memory. Something Gail finds amusing: she’s nuts.

For Scorsese, then, being an urbanite implies being exposed to eccentricity, to that which escapes the norm, to unpredictable, erratic behavior (Julie), if not outright lunatic (Gail). Behaviors that come from perfect strangers, and this is important because the fear of the unknown has a crucial effect on the development of the night that Hackett lives.

This distrust of the stranger is not shared by all the characters. Marcy, for example, has no qualms about inviting Hackett, whom she has just met in a restaurant, into her home. Kiki is almost more sympathetic to Marcy’s flirt than to her own roommate. And Tom, the bartender, would be in an intermediate position: he ends up leaving his house keys with Hackett so that he can go check if the alarm is on or if he has been a victim of the wave of robberies, but then he closes the bar to go check it himself when he sees that Hackett does not return and, in addition, he is the one who betrays the troubled protagonist to the crowd that chases him in the final third of the film.

But the idea of fear of the unknown is ultimately what abruptly brings the film into its third (and delirious) act. It’s an idea that comes early in the story when Marcy explains to Hackett that she was once raped by someone who entered her room through the fire escape. Then, in a hilarious twist, she reveals to him that the intruder was her ex-boyfriend, but by then little of that detail matters: that quote is relevant to the atavistic fear of desecration of the home by a stranger, something that cinema would later exploit in the horror subgenre of the home invasion, because from that quote then emanates all the distrust of the neighbors of SoHo, the New York neighborhood of Manhattan where all the action takes place, who spontaneously organize themselves into an urban commando that pursues (wrongly) Hackett believing that he is the thief who is stealing from their homes.

But the film deals with this fear in a sarcastic way, almost mocking it. The real thieves are two small-time crooks played by the comedy duo of Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong, very famous at the time in the United States, but not very successful in exporting to foreign markets. They drive around the neighborhood in a rickety van stealing what used to be stolen back then, televisions and VCRs, as well as other valuables. It is ironic, then, that the fear of the neighbors has its origin in two harmless and friendly crooks, so clumsy that they are able to pay money for a sculpture that they then lose. This is what happens when you pay for something, they steal it from you —says one of them in one of the best lines of the whole film.

It is certainly a gentle portrait of an urban crime that After Hours avoids depicting in the usual way that the cinema of the time did. From the seminal The Warriors (1979) to 1997: Ransom in New York (1981), passing through the horror genre that saw a vein with products as sinister as Maniac (1980) or exploitation films from Italian cinema set in the (then) troubled Bronx neighborhood: all of them are films that describe a New York in which crime and violence run rampant.

After Hours shies away from such a tremulous narrative. The night in the New York of After Hours is like a labyrinth of lonely souls, possibly those of Hopper in Nighthawks, and therefore its streets are anything but threatening: they are fascinating with their everlasting wet asphalt, and they are electric with the daring cross-cuts with which the great cinematographer Michael Ballhaus describes them. They are streets that harbor inviting spaces like the very studio where Marcy and Kiki live, where there are hardly any light sources.

Fascinating, attractive, exciting are adjectives in which Hackett, a normal man, would want to stay and live in this night that the film narrates. A normal man looking for the opposite of the routine of his job, looking for adventure. But these are also adjectives that turn against him, that derive in an odyssey that escapes his control and in which everyone seems to want to accuse him of something that has nothing to do with him, who is a man with a serious and orderly job. In this final stretch of the film there is a revealing moment that admirably synthesizes this moment that Hackett is going through. It is when he contemplates a murder through the window of a building, a woman gunning down a man: Hackett’s paranoia is such that his immediate reaction is to say to himself Surely I’m accused of that too.

Those same streets that promised excitement and adventure, then, are the ones that trap Hackett in his desperate attempt to return home, to that sacred, inviolable, safe space that is the unwitting protagonist of the film. Just in 1985, Phil Collins closed his masterpiece No Jacket Required with a song entitled Take Me Home, in which the narrator described himself as a normal man “who works by day and sleeps at night”. That’s Paul Hackett: a normal man who just wants to go home, a normal man caught in a cry of stupor at the surreal events that happen to him in a single night.

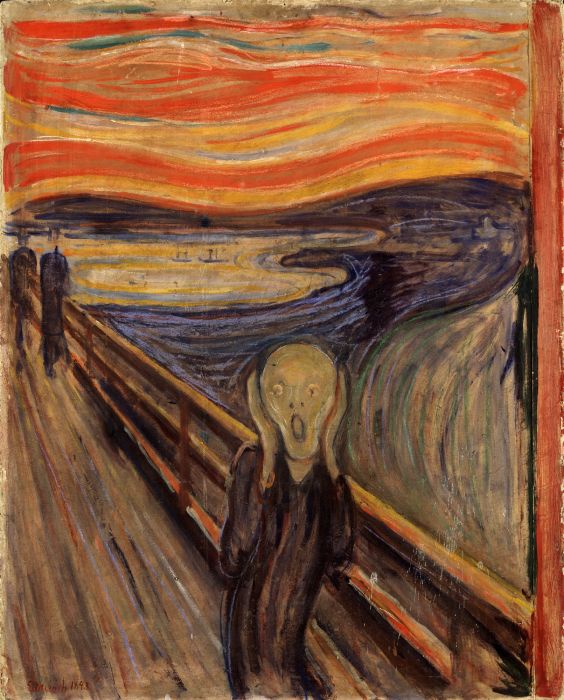

And the film, finally, decides to resort to literalism and ends up locking Hackett in a scream: to escape the mob that wants his head, another artist who also makes sculptures locks him in a human figure that, although it is not screaming like the one Kiki was molding at the beginning of the night when Hackett meets her, it does bear a great similarity to that one, inspired (explicitly, since it is named in the dialogues) in Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

The Scream (Edvard Munch, 1893).

The final irony of the film is devastating: with Hackett literally trapped in his own scream, the two crooks enter the workshop and steal the sculpture. They load it into the van, speed off, but in their escape the back doors open and the sculpture falls to the asphalt, shattering. Hackett, freed, gets up, to discover that he is right in front of the doors of his work, which at that moment open for him.

A new working day has begun. The cycle has closed. The night has ended, which is a space where strange creatures dwell as Raf explained in the unforgettable 1984 disco hit Self Control: I live among the creatures of the night, I don’t have the determination to try to fight a new tomorrow, so I guess I’ll just believe that tomorrow never comes.

The light of day makes the vampires of the night seclude themselves in their abodes. Work, routine, is the salvation of modern man, the place where order reigns in contrast to the chaos of the night. Few morals can be found in the cinema of the 80’s more devastating than this one.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!