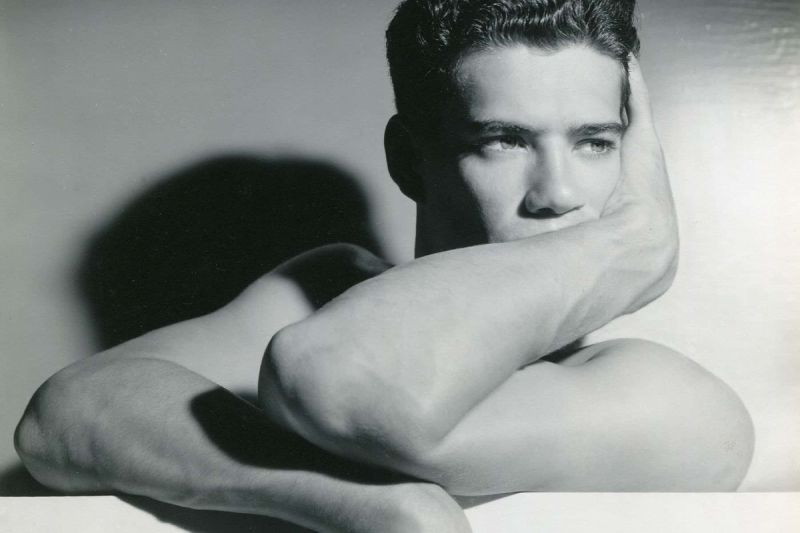

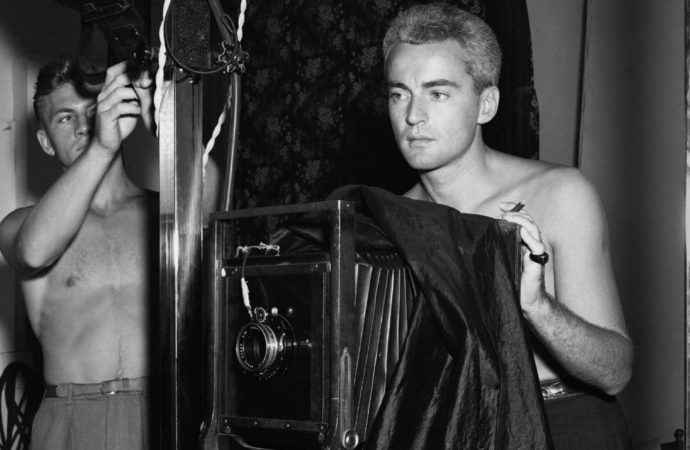

The 26th Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival, taking place between March 7 and 17, has presented in its program several feature films that, from different points of view, bring us closer to figures of artists consecrated or marginalized by history, with impeccable or improvised careers. Master photographer George Platt Lynes has been glossed in the black-and-white documentary Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes (2023), directed by Sam Shahid, which premieres in Greece (Open Horizons Section) after winning the award for Best Breakthrough Documentary at the last San Diego Festival. For those who are not familiar with the figure of this artist, it will suffice to recall the iconic portraits of movie stars that he made during his Hollywood period, such as those of Burt Lancaster, Katharine Hepburn, or the famous nude of Yul Brynner (1942). His fashion editorials, interest in ballet and above all his great passion: the male nude, show a recognizable personality, with an inspiring legacy from which artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe benefited.

Platt Lynes’ images, in which he himself sometimes participates, are revolutionary, with an elegance that matches his audacity. The director shows us the journey of a precocious artist who travels to Paris in the 1920s to enter directly into the circle of Gertrude Stein. Between the 1930s and the 1950s, the photographer’s stylized sophistication, his beauty, his lifestyle —which included the love trio he formed for years with editor Monroe Wheeler and writer Glenway Wescott— and his important collaboration with the celebrated Alfred Kinsey —whose Institute in Indiana holds one of the world’s largest collections of male nudes— made him an unrivaled figure. Back in New York, after his Californian period, he moved away from the commercialism then cultivated by Irving Penn or Richard Avedon, and shortly before his premature death he got rid of a large part of his collection, destroying it forever.

Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes (Sam Shahid, 2023).

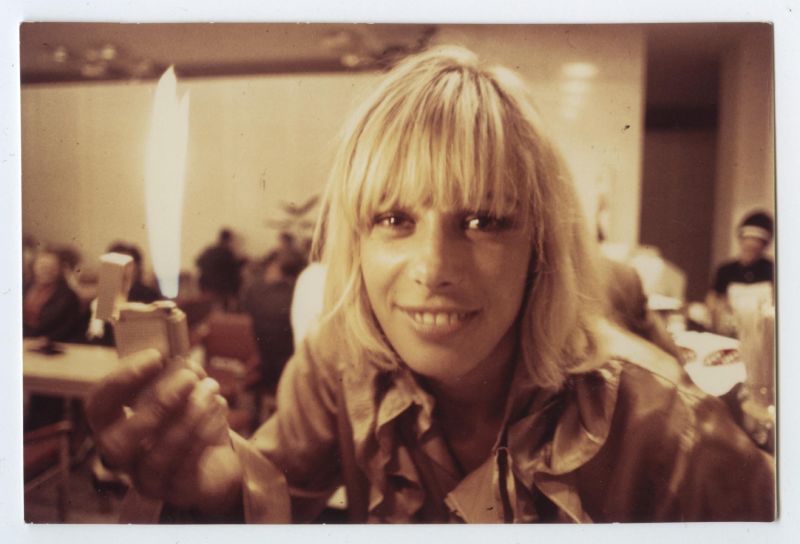

Another star with a vindicable career is Anita Pallenberg, the German-Italian model and actress, whose career has been publicly reduced to little more than having been the muse of the Rolling Stones when in fact she was a remarkable and talented performer, with a lifestyle so typical of the wild side of her time, that she became a legend. Catching Fire: The Story Of Anita Pallenberg, directed by Alexis Bloom and Svetlana Zill, is a respectful documentary, selected in the Open Horizons section, that treats with sensationalism-proof scrupulousness the life and work of the woman who was the partner of bassist Brian Jones and had a long and tumultuous relationship with Keith Richards, the father of her children.

Pallenberg’s energy and passion, which exerted an irresistible magnetism on those who knew her, not only served to encourage or inspire her partners, but also to attract great film directors such as Roger Vadim (Barbarella, 1968) and Nicolas Roeg, who, in Performance (1970), paired her with Mick Jagger and Edward Fox. In this sense, Volker Schlöndorff, who offered her her first film role in Mord und Totschlag (1967), reveals a woman gifted for acting and possessing an infectious creative energy.

Catching Fire: The Story of Anita Pallenberg (Svetlana Zill, Alexis Bloom, 2023).

The interview with the German director and the images of the film’s premiere at the Cannes Film Festival convey a freshness and joie de vivre, which will contrast with others of the abundant documentation based on home movies, showing (sometimes painfully) a lifestyle on the edge and her struggle to keep her family together, despite the omnipresent influence of drugs. Catching Fire: The Story Of Anita Pallenberg is a narrative that envelops us in a psychedelic chromaticism invaded by the imposing smile of its protagonist, sparing us the excessive imposition of irritating talking busts, fortunately prioritizing visual power. The vital maximalism of Pallenberg, who continued to work almost until his death in 2017, is narrated in first person with the voice of Scarlett Johansson, thanks to her discovered diaries. The film is produced by his eldest son, Marlon Richards.

The Real Superstar (2023) is, on the other hand, like a continuous grindhouse session, that is Cédric Dupire‘s finely tuned approach to the colossal figure of Indian cinema, Amitabh Bachchan, whose career over half a century has marked generations of viewers. Thanks to his presence on screens, in every imaginable type of advertising, his business dealings and politics, Bachchan (and his family) are the pinnacle of Bollywood Gotha, and Dupire’s wordless tribute is a pure orgy of galloping editing, drawing on fragments from more than 200 films he worked on. This editing work without respite, with no textual or referential support other than pure action, is a pure maelstrom of chases and histrionics, where in chronological order, film after film, we see a myth take shape.

The Real Superstar (Cédric Dupire. 2023).

The clickbait title of Daphne Baiwir‘s film, Le film pro-nazi d’Hitchcock (2023), is the least apt of her endeavor. On the other hand, happily, it traces a well-documented and contextualized history of the story of Lifeboat (1944), which the British filmmaker directed at such a convulsive historical moment, that this is the only way to understand the discrepancy of interpretations that the film provoked, its political and social dimension in the midst of World War II. Starting from the massive milestone of the publication of The Grapes of Wrath and the subsequent success of the film directed by John Ford in 1940 and starring Henry Fonda, Baiwir places us in an era where political awareness, the exaltation of American values and human rights pivoted between propaganda, militancy and accusations of treason, as shown in the films of Capra, Ford, Huston and Hitchcock himself.

Lifeboat (Alfred Hitchcock. 1944).

After several films in which he defended the U.S. entry into the war (in violation of the Neutrality Act), Alfred Hitchcock commissioned Steinbeck, who was committed to the war effort, to write the screenplay. However, so many were the changes and the hands through which the script passed —Alma Reville, MacKinlay Kantor, Patricia Collinge, Albert Mannheimer and Marian Spitzer, in addition to Ben Hecht, whom the director asked to rewrite the ending— and the substantial variations on the social background of the protagonists and the stereotypical treatment of the African-American character, that Steinbeck requested that his name be removed from the promotion of Lifeboat. The eventful production and shooting were followed by an unusual controversy after the film’s release. What if it turns out that instead of being an anti-Nazi propaganda film, it is defending the superiority of the Germans over the Allies?

The Andersson Brothers (Johanna Bernhardson, 2024) traces a portrait of Swedish director Roy Andersson and his three brothers: Kjell, a documentary filmmaker, Ronny, a methamphetamine addict who would die after a long period living on the streets, and Leif, the director’s father. Starting from her childhood in a working-class family in Gothenburg, with a politically committed father who made a living selling potatoes to home delivery, Johana Bernhardson devotes her first feature film (selected in Open Horizons) to delving into the origins of family breakdown, alcoholism and the weight of generational legacy. In a valiant attempt to reunite the four siblings, separated for years by their own will, the director traces a chronicle of dreams, successes and truncated lives. The various tragedies that traverse The Andersson Brothers lead us to the end of the career of the director of Du Levande (2007), in an unthinkable and unexpected twist of fate.

The Andersson Brothers (Johanna Bernhardson, 2024).

Arnaud Lambert and Vincent Sorrel ask themselves in Only Godard (2023), selected in Film Forward section, how to elaborate a portrait of Jean-Luc Godard, of his methodology and universe, of his way of constructing or deconstructing cinema, that is on a par with their own cinematographic audacity and genius. From an immense film archive-warehouse in the center of France that houses films and documents deposited by distributors, where since 2010 there are also all the archives kept by Godard in Switzerland, they create a double of the director, who assumes the role of our guide in his world. Imitating his voice, an actor reads excerpts from his writings and, in a rather repetitive way, tries to delve into his creative process, in a film essay in which the excessive recourse to this character detracts from the film’s interest, to the detriment of a documentary treasure that, despite being treated emulating the most characteristic features of Godard’s cinema in his last period, is not adequately enhanced.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!