The year 1976 became the dividing line that marked the transition of an entire genre from complacent decline to utter irrelevance.

The American Western film genre had, until then, been firmly established in the collective unconscious of the country that gave birth to it, as it recounted the process of its consolidation, embellished by an epic that often veered towards self-indulgence.

Almost 50 years ago, a death certificate was signed that had been forged throughout the decade through a series of epitaphs that, at the time, did not sound like such. Western films continued to be made sporadically after that date, but it is clear that the next phase did not involve a reinvention, since those who could have led it, such as Sam Peckinpah and Sergio Leone, had changed their style or were struggling with very long-term productions.

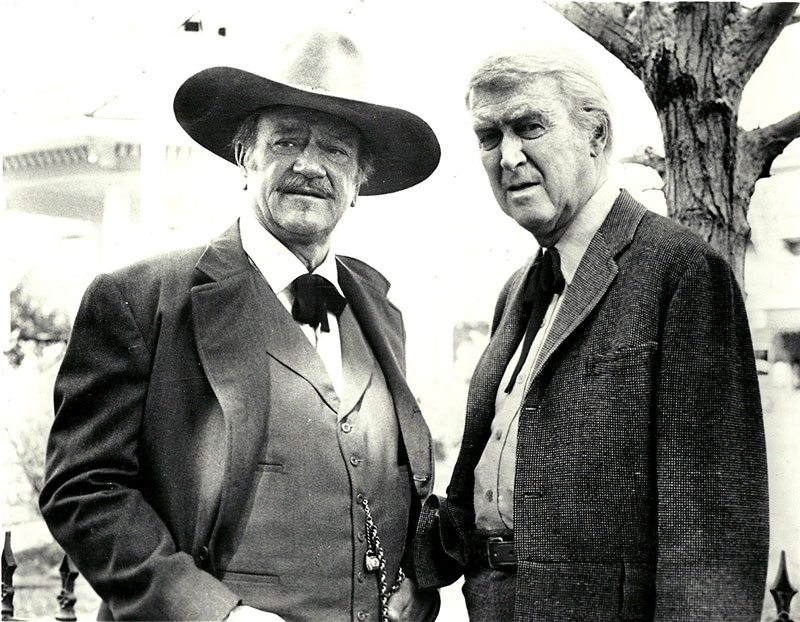

The Shootist (Don Siegel, 1976)

The Shootist is John Wayne’s swan song, the greatest representative of the classic western, and has a testamentary quality that applies to both the actor and his character. Served through the last days of an old-school gunfighter, who comes to settle the scores he owes to the town where his fame began, it contains all the ingredients of a farewell, including an introduction that is in itself a tribute, through which some clips from classics such as Red River (1948), Rio Bravo (1959) and El Dorado (1967) parade as a figurative biography of the protagonist.

This process of building the legend clashes brutally with the close-up sequence of the old man slowly arriving on horseback in the town of 1901, which accepts him only as a relic. Ten years of fighting the cancer that is actually killing him are reflected in the emaciated face of a Wayne who is running on empty.

The Shootist fails to be memorable, has gaps, and feels longer than its hour and forty minutes. The direction is bland, almost television-like, and someone as competent as Don Siegel seems uncomfortable with the material at hand. However, Wayne ends up being the glue that holds everything together, especially when he is joined by a series of recognisable luminaries who have come to support him in his efforts: his comrade James Stewart, the efficient secondary villains played by Richard Boone and Hugh O’Brian, the Fordian John Carradine, not to mention Elmer Bernstein (composer of the original score for The Magnificent Seven). The entire story is planned to converge in the climactic duel in the saloon, ten minutes filmed in exemplary fashion where emotion overflows, as it must when witnessing the end of an era.

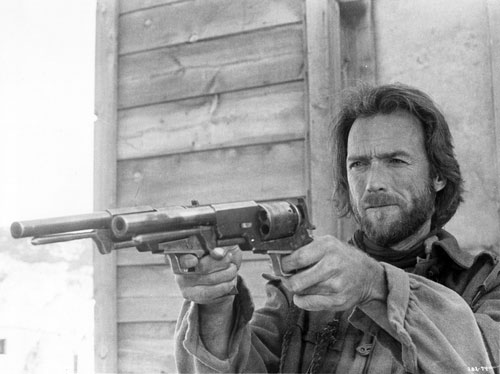

The Outlaw Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood, 1976)

On the other hand, we have Clint Eastwood, Wayne’s mirror image and standard-bearer of the bastardised evolution of the genre that came from Europe through Sergio Leone’s early forays into it. Eastwood had not yet found the necessary skill to distance himself from his master’s ways when he was pushed to replace Philip Kauffman at the helm of The Outlaw Josey Wales (Clint Eastwood, 1976).

This road western works better than The Shootist, thanks to a script that pampers the character of the gunman seeking revenge, betrayed by some of his old comrades and pursued by a cloud of bounty hunters, who attracts a colourful troupe of losers and hustlers who, by choosing him as their guru, end up humanising him and distancing him from the archetype.

The Outlaw shows the first brushstrokes of the author who, today, is considered the last classic, but, all in all, Eastwood will only return to the West twice more, and in both cases to sign outstanding works.

The Missouri Breaks (Arthur Penn, 1976).

A director as reliable as Robert Altman turns Buffalo Bill and the Indians into a kind of semi-documentary work, in which well-intentioned people like Paul Newman and Burt Lancaster are subjected to a story that seems more like a straitjacket. The Missouri Breaks (Arthur Penn, 1976) is an exercise in continuous demystification that makes almost all the characters who parade through it unsympathetic, risking everything on the possibility of bringing together two actors not particularly suited to westerns, Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson. This mixture of brilliant elements cannot gel in such a twilight exercise, but it works perfectly as a reflection of its time.

In Europe, the spaghetti western subgenre survives by fits and starts, replacing the hyper-realistic ugliness of its more conventional offerings with the crude comedy of the successful Trinidad series, which gradually undermines the slim chances of an industry that created a whopping 500 titles in just 15 years of existence.

Keoma (Enzo G. Castellari, 1976)

Keoma (Enzo G. Castellari, 1976) is perhaps the last serious attempt to keep a hammering production system on life support, which provided work and notoriety to many low-profile professionals who would later jump to giallo or S-cinema. What comes next is insignificant, and even changes scenery (the golden age of the ‘Romanian’ western arrives).

Since then, there have been attempts to resurrect the deceased. In some cases (usually under Eastwood’s direction), they have become instant classics that have even led to talk of a revival of the genre. But there have been more commendable attempts (Costner) or rehashed homages (Tarantino), not to mention truly awful products that have not even acknowledged their ability to poke fun at themselves.

But it was 50 years ago, when a whole narrative about the difficult adolescence of a country under construction was slowly being pushed aside, driven by political intrigues, post-Vietnam attitudes, lone vigilantes immersed in dystopian universes when not directly thugs, or interstellar adventures at the hands of George Lucas, who in 1976 decided to film his own western with laser swords, set in a galaxy far, far away from Monument Valley.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!