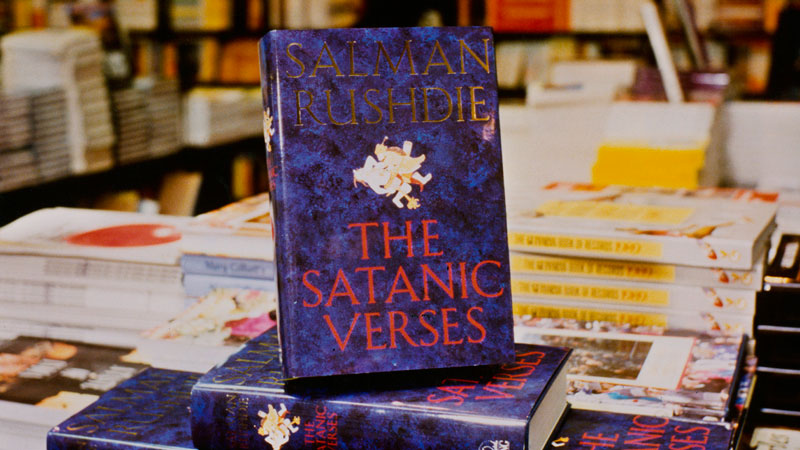

The Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie’s 1988 sprawling novel, is possibly the most hated book of the late 20th century. And yet, its opponents are not likely to have left many fingerprints on its pages. This is due to a combination of factors: profusion of storylines, spatiotemporal shifts, intertextuality, disjointed narrative, unclear scenarios, Anglo-Indian slang, and blasphemy. And of course, even in 1988, it was the last that made all the headlines.

The novel is unique in our times in that many of its detractors not only haven’t read it, but would never read it as a matter of principle, for someone has told them that it is blasphemous. And that informant was probably informed by someone else, in a chain that presumably goes back to an Original Reader who first checked that there was blasphemy, and who surely did not continue to read after that page.

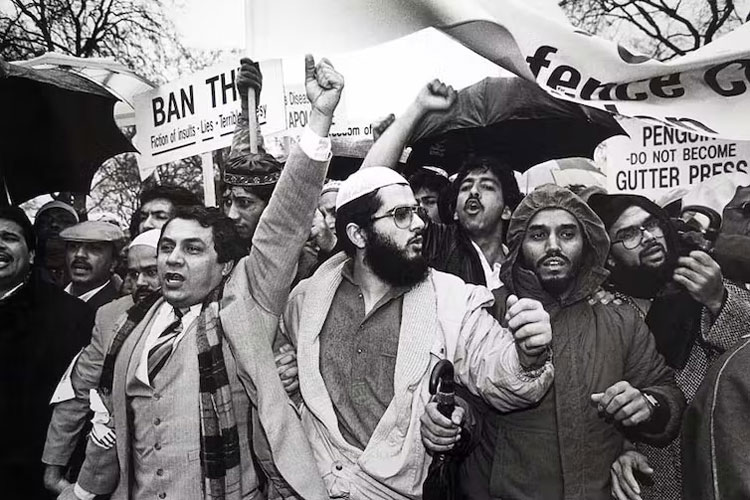

The blasphemous nature of the book incensed people in India, Pakistan, and England, but, especially, the Supreme Leader of Iran at the time, Ayatollah Khomeini, who issued a fatwa (Islamic ruling) calling on all Muslims to kill Rushdie and All those involved in its publication who are aware of its content. As a head of both Church and State, Khomeini granted the right of heavenly asylum to those who would perish during the mission.

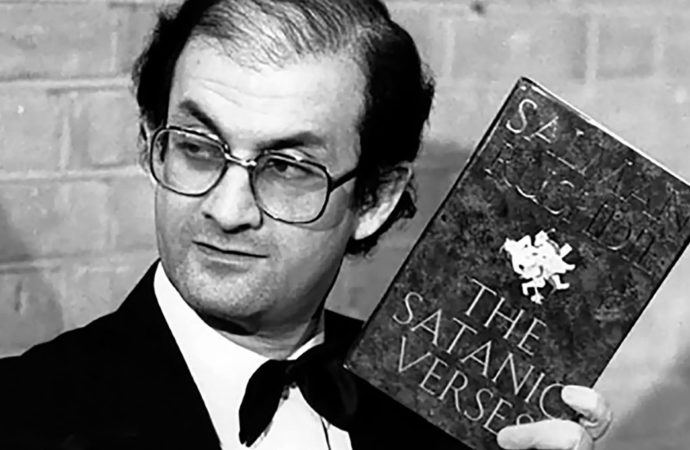

The Japanese translator, Hitoshi Igarashi, was found murdered. The Italian translator, the Turkish translator, and the Norwegian publisher each survived an assassination attempt. The writer had to live in hiding until 1998, and was viciously stabbed in New York in August this year.

What is disappointing about this controversy is that The Satanic Verses is not at all an anti-Islamic libel. It does have some mockery, well into the plot. Its portrayal of the Prophet (here ‘Mahound’) does not come off as very appealing, and the names and identities of his wives are used by the workers of a brothel, a gimmick that becomes a success in the city. As the plot progresses, Mahound begins to sound like a self-serving prophet who issues ‘revelations’ whenever it suits him. All this is more or less gratuitous—and you don’t have to be a believer to feel at least slightly offended—but there is also the reference to an ancient, contentious legend.

According to some early biographies, the Prophet received a message allowing the worship of three local goddesses of Mecca, only to discover that the message had been inspired by the Devil himself. After the quranic verse where he is asked,

Have you considered Lāt and ʿUzzā? and Manāt, the third one? (53:19-20)

Satan reportedly made him add:

These are the exalted gharāniq [cranes?], whose intercession is hoped for.

The ‘satanic verses’ legend would be rejected by later scholars and excluded from the canonical compilations of hadith (traditions about the Prophet). There is no trace in the Quran of that line which, in the legend, was soon replaced. In Rushdie’s novel, the goddess al-Lāt kills Mahound in revenge for his change of mind.

And there is one more offense in the plot: a dark, nebulous character, ‘the Imam,’ a religious leader in European exile who would seem to be inspired by Khomeini himself. Some say the fatwa was intended to protect at least two honours.

So he was sentenced to be beheaded, within the hour, and as soldiers manhandled him out of the tent towards the killing ground, he shouted over his shoulder: “Whores and writers, Mahound. We are the people you can’t forgive.” Mahound replied, ‘”Writers and whores. I see no difference here” (The Satanic Verses)

In the light of the ensuing controversy, it might seem that The Satanic Verses has little to add to our understanding of religion, with the exception of new ways of deriding and ridiculing it. That would be the wrong conclusion. The contents and very tone of the novel can be read as a reflection on the religious dimension and the possibility of miracles in the contemporary world. The lovely story of the girl-seer who leads an Indian village to Mecca (Chapter 8), in the belief that a path would open in the Arabian Sea, skilfully captures the lights and shadows of popular religion in Rushdie’s native subcontinent (and is based on a true 1983 mass suicide). The narrative is unclear as to whether the villagers drowned or managed to cross the ocean on foot: whether it was a matter of faith or madness, or of something else that makes them synonyms.

Rushdie was raised in a liberal Muslim family in Bombay, lost faith at the age of fifteen and became even less of a believer after some Islamic collectives started burning effigies of him in 1989 (though, at the apex of despair, he pretended to convert and called for the book’s withdrawal: The biggest mistake of my life). In the Mecca pilgrimage story, the author peeps through the eyes of his character Mirza Saeed, who travels along with the pilgrims in a car, trying to convince his ill wife that they’re falling for suicidal nonsense. He sees his wife and the other villagers drown in the ocean, although everyone else would claim to have witnessed the prophesied parting of the waters, and, in his final hour, he has to concede that they were right.

Both the fictional and the real story of The Satanic Verses are the result of a complex interplay between faith and scepticism, magic and naturalism, fact and fiction, and, most notably, between each other.

A book that describes people’s lives being invaded by products of their imagination.

A writer who is sentenced to death for a product of his imagination.

The unbridled imagination that he poured into history flew back to him, like a deadly boomerang, and nearly sent him to history books.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!