In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the kitchen became the epicentre of the home; until then it had been distanced from the living space and cluttered with furniture and knick-knacks. But the introduction of electricity and the adoption of plumbing began to transform kitchens into a comfortable place where families and friends gathered to cook, eat, chat and relax.

In these years, more and more women are working and need practical and efficient kitchen solutions. This led to the creation of the so-called work triangle, in which the hob, sink and refrigerator are arranged in such a way as to avoid unnecessary trips.

In 1902, the American magazine House Beautiful described what the ideal kitchen of the future should look like: something like the kitchen of a Pullman train carriage, the kitchen of a yacht, a laboratory and the cleanliness of a doctor’s surgery. Let’s keep the paragraph because it will make history.

Women Take Over

Traditionally, women’s role in society has been reduced to caring for the family with little or no impact outside the domestic sphere. But if we look back to the 1920s, we have a broad perspective on how women handled the social advances of the time.

Many of these women were part of the enlightened bourgeoisie but, even in these conditions, they had to fight against discrimination and sexism to make a name for themselves in the industry. Nevertheless, their inventions in the kitchen have improved the lives of millions of people around the world. Here is a selection from the best known group:

Sarah Guppy, from Birmingham, UK (1770-1852). Her numerous kitchen and household inventions include a kettle that can steam eggs while boiling water and the first toaster for bread. He also invented an extractor hood, the fire sprinkler system, a bed for women to exercise on, and a new type of candlestick that made better use of candles.

Margaret Knight, from York (Maine) USA (1838-1914). Her best-known invention dates from 1871 and is a machine that automatically folded and folded flat-bottomed paper bags; a type of bag that is still used mainly in food shops and which has returned to the street after the abuse of plastics.

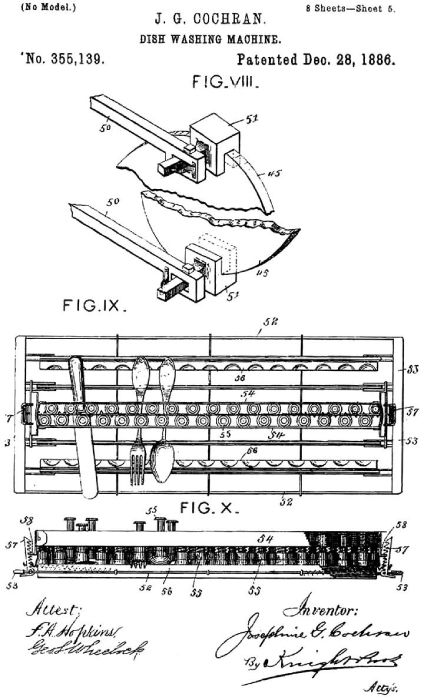

Josephine Cochrane born in Ashtabula (Ohio) USA (1839- 1913) is the inventor who designed and patented a hand dishwasher in December 1886. The invention consisted of a wooden wheel placed over a copper kettle. A motor turned the wheel while hot water and soap sprayed the dishes.

Dish Washing Machine Design. J. G. Cochran.

Mary Engle Pennington, from Nashville (Tennessee), USA (1872-1952). She is a pioneer in the preservation and transportation of perishable foods. She developed standards for the safe processing of chickens raised for human consumption. She devoted her career to the study of refrigeration and its application to food freshness and safety.

Florence Parpart, born in Hoboken (New Jersey) USA (1873-1930). In 1900 he obtained his first patent for a street sweeping machine. But her breakthrough came in 1914 with the first electric refrigerator, a direct precursor of the modern refrigerator. He also invented a window cleaning device, which he patented in 1916.

Florence Parpart.

Lillian Gilbreth, from Oakland (California), USA (1878-1972). An engineer and mother of 12 children who invented the pedal-operated bin. She also invented the electric mixer and refrigerator door shelves.

Virginia Holsinger of Washington (1937-2009). Member of the Agricultural Research Service of the United States Department of Agriculture. Her research on enzymes and digestion contributed to the creation of nutritious powdered milk substitutes that were used to help sustain soldiers on the battlefield and people in need of humanitarian assistance around the world.

Melitta Benz from Dresden, Germany (1873-1950). In 1908 she invented the coffee filter and founded a family business under her name: Melitta. In 1936, she created a filter that narrows downwards in the form of a slit. He also launched coffee filters known as filter bags.

Germany Devastated by World War I

Since the 19th century there have been a series of contributions by women researchers who, from different positions, have been proposing a change of perception in order to integrate women’s lives, as organisers of the home, into the new economic and social order that was being forged between the 19th and 20th centuries.

The pioneers in this field of research were the North Americans Catharine Beecher (1800-1878), Christine Frederick (1883-1970) and Lillian Gilbreth (1878-1972), whose reflections and proposals did not question the home as the appropriate place for women, but rather the design and organisation of the home.

In Europe, the second decade of the 20th century was deeply affected by the consequences of the defeat of the German Empire in World War I, resulting in widespread unrest in German society. During this period, the social housing on which American domestic engineers had theorised became the main protagonist of architecture in European countries such as Germany, Austria and Holland, with outstanding architects and designers such as the Austrian Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, the Germans Erna Meyer and Benita Otte and the Dutch Truus Schröder.

The avant-garde Bauhaus school, founded in 1919, had a high percentage of female students in its workshops. The Bauhaus was not a school of architecture —in fact, there was no architecture workshop until 1927— but what we would today call a school of industrial design. However, through the projects of its directors Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, all architects, it played an active role in the evolution of architecture in the Weimar Republic.

The exhibition consists of an experimental dwelling designed for the new man of the 20th century. Among the team members is Benita, who is in charge of the kitchen design. In 1996, the award-winning building was listed in the Unesco monument preservation programme and declared a World Heritage Site of the 20th century.

In 1918 the first woman architect graduated from the Vienna School of Applied Arts. She was Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (born Margarete Lihotzky), a young woman from a bourgeois family born in 1897. Her father is a civil servant and her mother is a friend of Bertha von Suttner, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, and of the painter Gustav Klimt himself, whom she asks to help her daughter get into the Vienna School of Applied Arts, one of the few universities that accepted women.

Christine Frederick.

One of her teachers was the architect, scenographer and sculptor Oskar Strnad, who sent Margarete to the working-class districts for research, thus laying the foundation for her lifelong high level of social responsibility. After the war Vienna is plagued by famine and an extreme shortage of housing. In the 1920s alone, the city built more than 60,000 flats. Under the Habsburg monarchy, most architects worked for the elite. But Lihotzky advocated social architecture, which would improve the living conditions of the working class.

Margarete is not alone; many architects and artists decide to put their skills at the service of ordinary people. In Berlin, a workers’ council for art is set up, which promotes public buildings, organises exhibitions of amateur architects and develops many of the ideas that would later materialise in the Bauhaus.

And he began to work in the so-called Red Vienna, a period between the end of World War I in 1919 and the arrival of National Socialism to the German government in 1933. This was a historic moment when the Social Democratic Party seized power in the city and ordered the construction of 65,000 houses, many of them designed by Lihotzky for the poorest people. Lihotzky’s social commitment was growing.

The Iconic Kitchen That Remains

In 1926, the Frankfurt City Councillor for Urban Planning, Ernst May, gathered a group of German and foreign collaborators from different disciplines. Margarete devoted herself to the construction of flats and the rationalisation of domestic work. She gives numerous lectures, designs residential building projects and develops her famous kitchen plan, which will be installed in more than ten thousand new flats.

And it is here that Lihotzky becomes immortal in the memory of design. He created the famous Frankfurt Kitchen. It was the first modern, mass-produced fitted kitchen, which occupied only 6.5 square metres and whose sophisticated functionality was implemented in some 10,000 flats in order to rationalise cleaning.

In addition to Benita Otte‘s Haus am Horn, the Frankfurt Kitchen was inspired by Margarete’s earlier project for the small kitchen in luxury trains, which was based on Taylorism, which advocated the organisation of work in order to make it more effective, and which was also applied to household tasks. Lihotzky organised the kitchen in such a way that there were as few steps as possible to move from the cooking area to the work area, and from there to the water area.

In the centre of the wall is a window for light and warmth. Under the window is a worktop with a swivel stool. On one side there is a sink with a hot and cold water tap, above it a dish drainer, a sliding rubbish drawer which could be emptied outside by means of a vertical drainer, a vertical container for cleaning utensils and a radiator. Tall and low cupboards without legs are installed, finished with a plinth for easy cleaning. Aluminium compartments are fitted for bulk goods such as flour, rice and sugar. On the other side is the cooking area and oven.

Cocina Frankfurt.

It also has substantial technological advances, such as the replacement of the coal cooker with an electric cooker, thus eliminating soot in the kitchen. Today the Frankfurt cooker is an icon of modernity, reproduced over and over again. And the great paradox is precisely that it is still unknown today that today’s kitchen designers do nothing more than reproduce the kitchen designed by Margarete in 1926 to equip social housing.

Commitment, Resistance and Imprisonment

In Germany, Margarete pursues her career with her husband, the German architect Wilhelm Schütte, with whom she shares a strong ideological affinity. But she did not find the radical political culture of her hometown in Frankfurt, and she became less and less convinced by the German Social Democrats. On the other hand, he came into closer intellectual and personal contact with the members of the Frankfurt School, which marked a change in his political commitment. In 1927, three right-wing paramilitaries accused of murder were acquitted, triggering a general strike and riots that ended with the burning of the Palace of Justice. In view of these incidents, he moved closer to communist positions and established close contacts with the Soviet Union. In 1930 he joined the May Brigade, a group of 17 communist architects led by Ernst May, who moved to the Soviet Union, where he began to design kindergartens and master plans. In the USSR, he spread the principles of the Montessori Method in the design of schools and even in baby furniture.

Cocina Frankfurt.

But things change in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, when Stalin’s government starts arresting foreign experts. Lihotzky managed to escape persecution, but many of her former collaborators were not so lucky. In 1938, she moved with her husband to Istanbul, where she accepted commissions from the Turkish Ministry of Education: she designed a secondary school for girls in Ankara and a rural school in Anatolia. It was in Istanbul that she came into contact with Herbert Eichholzer, an architect who had worked for Le Corbusier before leaving architecture to join the fight against fascism. While in Turkey, Margarete joined the Austrian Communist Party.

In late December 1940 she travels to Vienna to join the Resistance, but is arrested by the Gestapo a few days after her arrival and sentenced to death. Eichholzer is arrested by the Nazis in 1943, sentenced to death and executed in Vienna. Margarete’s sentence was commuted to fifteen years in prison and she remained imprisoned in Aichach (Bavaria) until the end of the war, when she was released by US troops. After her release she returned to Vienna and joined the movement to rebuild the capital. But her pre-war professional networks no longer exist; she only had a few important public commissions. In 1958 she went on a long study trip to Mao’s China and then worked in Cuba and East Germany in the following decades.

Margarete Schuette Llihotzky.

It was only at the end of the Cold War that he received the recognition he had long been denied. In 1985 he published his book Memoirs of the Resistance. At the age of almost 100, together with four other survivors of the Nazi era, she sued the far-right politician Jörg Haider for downplaying the significance of the Nazi death camps. In Vienna’s bars and nightclubs, the song “The Frankfurt Kitchen” by Rob Rotifer, whose grandmother had fought in the Resistance alongside Margarete, is a popular song dedicated to the architect.

The lucid and rebellious pioneer died in 2000, five days before her 103rd birthday. Years earlier, when she was in her 90s, she confessed to a journalist that she was fed up with always being asked about her cooking and confessed: If I had known that everyone was always going to talk about the same thing, I would never have made that damn kitchen!

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!