Sebastião Salgado (1944-2025) was for decades the voice of the world’s conscience that whispered to us not words but images. The images spoke of other worlds in this one, albeit barely. Worlds that, as a civilisation, did not make us look good in the picture.

Salgado seemed to speak to us from his pulpit, but his work was limited to reporting the consequences of selfish and often misguided choices that brought suffering to hundreds of thousands in exchange for their total invisibility. No one disputed this loudspeaker, for he had earned it. Before initiatives like Live Aid put the spotlight on the terrible humanitarian tragedies in Africa, Salgado had already been there, trying to give a voice to the outcasts of the Earth, always with the only company of his Leica camera.

The social photographer suffered a saturation crisis in the mid-1990s, after covering a series of conflicts, each one more terrible and dehumanising than the last. During that decade, his lens showed the struggle against the impossible of trying to put out hundreds of oil wells scattered across the Kuwaiti desert, destined to burn for months. A consequence of the senselessness of a war as stupid as any other.

Then he discovered that entrenched quarrels between brothers could create monsters, as the fratricidal wars of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s taught us. And as if all horror could be overcome. Salgado found in the Rwanda of 1994 the scene of a factional extermination, a genocide that in 10 days swept away nearly a million people, and provoked a new exodus of hopelessly defeated people. After weeks of seeing rotting corpses wherever he set his lens on the landscape, the social photographer found it materially impossible to take another snapshot of the barbarism. He had lost faith that it would serve any purpose, but above all, in our continuity as a species. A society that loved itself so little was destined not to be noticed but to disappear, like any harmful pathogen.

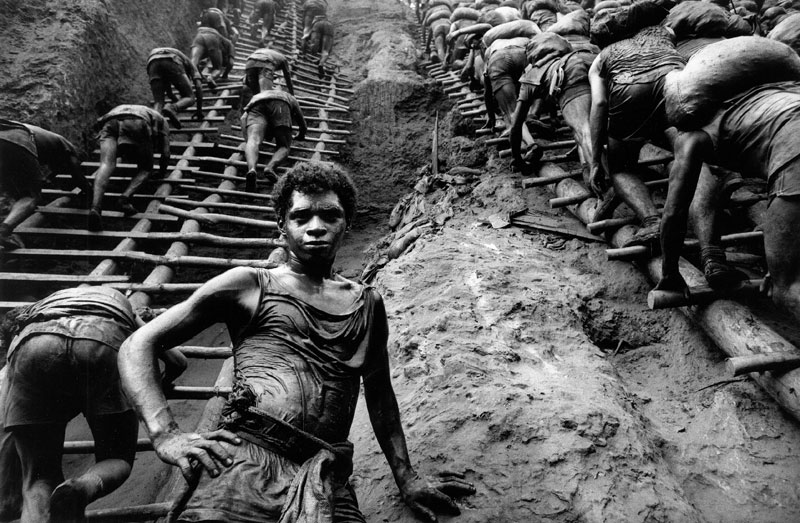

© Sebastiao Salgado

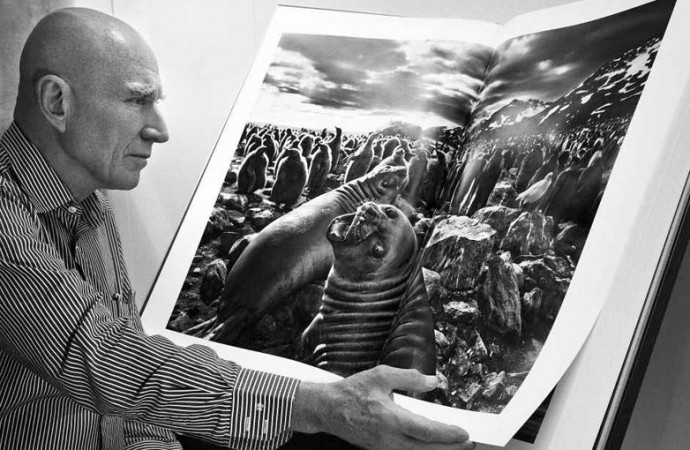

Sebastião Salgado’s recycling took him to the exact opposite of where he was. If, as a species, humanity was beyond repair, the landscape that appeared in the background was worthy of note. And remembered. Genesis (2004-2012) was a project intended to take us back to a time when the Earth was young, beautiful, and essentially innocent. An Earth unpolluted by us. Unexplored landscapes, almost virgin, evanescent, where the cycles of life took on their meaning, becoming part of the particular black and white of their captor. Genesis was an opening to hope for a Salgado who needed to heal many moral wounds. It not only changed the direction of his career but also extended it for another two decades.

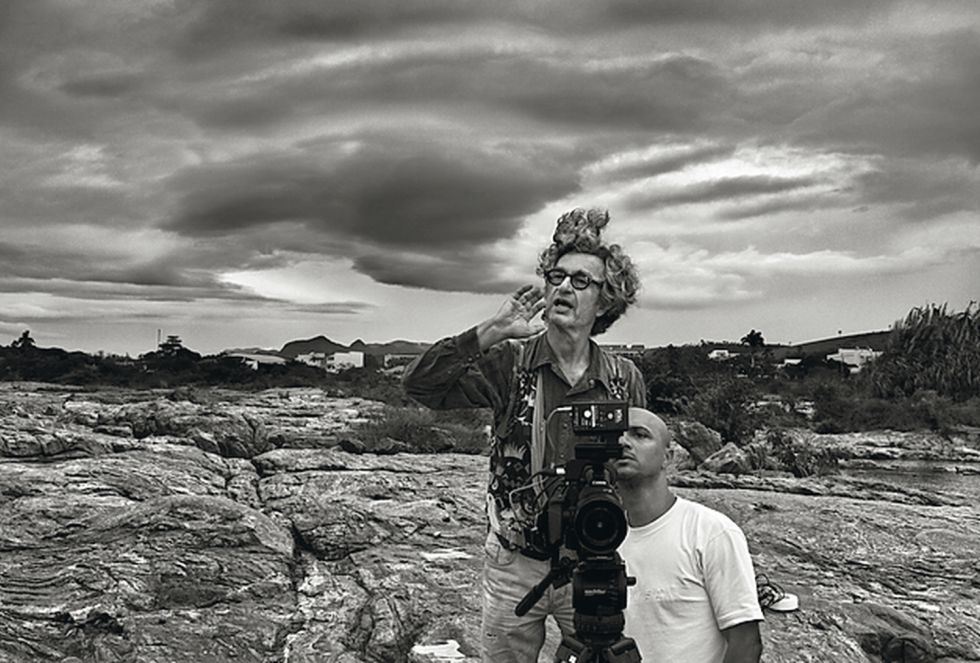

Wim Wenders had long had his eye on a possible collaboration with Sebastião, whom he admired for his ability to capture those moments that separate a reporter from a chronicler. The occasion was made real by filmmaker Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Sebastião’s first-born son. Juliano was looking to write a love letter to his father, and almost without expecting it, he already had someone to dictate it to him.

The Salt of the Earth (2014) turned out to be a happy encounter and a kind of greatest hits that the social photographer deserved. Through it, we learned more about this talented economist who, while working at the World Coffee Organisation, discovered the links that united and separated the first and third worlds, and the ethical motives that led him to fully embrace his passion, photography.

Wim Wenders shooting The Salt of the Earth (2014)

We discovered his first series of images: Other Americas (1986), which showed how misery shapes a human body from birth to death, even in the most remote and inhospitable areas of the planet, and Sahel, End of the Road (1984), ground zero of one of the most terrifying droughts of the century, which struck four nations around the horn of Africa, and left a flood of living dead migrating to nowhere. A hundred years will pass, and Salgado will still be remembered for these images of children and mothers reduced to a pair of enormous eyes, gazes that bring together the dismay of not being able to take another step because the body that sustains them no longer has any consistency.

We also discovered impossible images, such as those of the Serra Pelada mine, which inspired his series Gold (2020). A sort of infernal chasm where hundreds of desperate hustlers searched for the slightest hope of salvation, or mostly disappeared, swallowed up in its depths. Their crushed faces, covered in a mud so thick that it deformed their expressions into a jumble of sweat, despair and failure, led us to wonder how far the soul can go before it crumbles.

In The Salt of the Earth, we discover above all else a perfect pairing, that of Salgado and Leila Wanick, partner and architect of bringing this cry for help, summarised in the form of snapshots, to the rest of the world. Leila has been the compiler of everything that gives rise to the Salgado brand, and the extension of the social photographer when it comes to publishing his series of photographs and curating the exhibitions that bring us closer to his horror and his beauty.

Halfway through the documentary, when, like Salgado, we find it difficult to continue looking at the barbarity, the tone changes, as if someone had drawn the curtains of a darkened room. The light that floods in is that of the Instituto Terra. The Terra Institute is not only the card up its sleeve that complements a model documentary, it is one of those projects that justifies a life, repopulating with its original species a familiar piece of land that over the years has become a desert wasteland, and thus, reconverting it into a new jungle. A huge task that requires reinventing oneself, asking for all the help, creating a new team, and formalising a new commitment. Salgado cannot forget what he has seen over the years, but he can exchange suffering for hope, contributing a considerable ‘grain of sand’, 10 million new Atlantic forest trees, which in time will change the landscape and give it back a life that seemed lost forever.

And this macro-project is the genesis in turn of Amazonia (2023), Salgado’s photographic testament, a sort of continuation of Genesis, but circumscribed to the lungs of the Earth, where once again Sebastião shows us another planet, a supernatural landscape where the force of nature shows us as insignificant as our quarrels. The chronicler of inequalities places us for the last time as astonished observers of a beauty so pure that it demands only respectful silence.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!