The easiest thing to do would be to place Eleanor Coppola (1936-2024) in the shadow of her husband, Francis (Ford Coppola), patriarch and standard-bearer of a generation of filmmakers who changed the world and with it the way of making films that had prevailed for decades. When it comes to labeling it, it would be like that komorebi that Wim Wenders discovered for us a few months ago, that flash of sunlight that intermittently passes through the thick foliage between the trees. We guess its presence, but little more. Slipping between the handful of masterpieces that Francis was producing (especially in his magical decade, the 70s), Eleanor’s role would be that of a tightrope walker managing, not without difficulty, between the tons of ego, genius, and recklessness that her husband exuded.

But Eleanor was destined to go one step further, and her glimpses emerged from a muted, shadowy work, one that tried to explain with 16 mm images the dirty, stark reality on which those megaprojects were based. Narrating the excess from simplicity not only humanized them but also allowed us to see all the trompe l’oeil that ran through them, their shadow lines, and their miseries. And also to marvel when awards and recognition for visionary genius and the exact confluence of the stars emerged from those houses of cards.

Eleanor met Francis Coppola in his early days, under the orders of Roger Corman, in a production, (Dementia 13, 1963) whose recognition would derive from being the Opus One of its director, and also of one of its performers, Jack Nicholson. Eleanor and Francis were inseparable from then on, as their interests converged as perfectly as their way of understanding the business in which they moved. Their idea of family unity would lead them to gradually incorporate their children: Gian-Carlo, Roman, and Sofia.

When in 1970 Francis F. Coppola was commissioned, almost by rebound, to bring Mario Puzo and his King Lear to the big screen, Eleanor insisted to Francis that this this had to be the move he needed to make. The making of The Godfather (1972) would deserve its documentary in itself but, even without it, all the anecdotes collected are like a summary of any director’s notebook: a load of great ideas, a revolutionary way of catalyzing and dynamising them, and a host of internal and external setbacks, which often questioned his continuity at the helm.

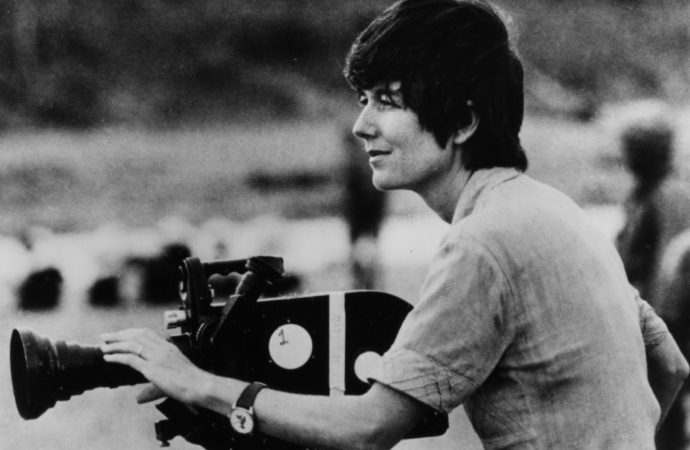

Eleanor and Francis on the set of The Godfather.

The story is well known. The Godfather and its enormous impact as a seminal work were followed by its sequel and then by that marvelous, almost nouvellevaguian production called The Conversation. In 1975 Francis Coppola was sweeping the US and Europe, he was the perfect catalyst between spectacle and art, and his genius seemed to know no bounds. He could navigate huge budgets and war economies, and indulge from his creative pinnacle in choosing and rejecting any project he pleased. In five years he had earned a freedom that other people begged for, without luck, throughout a career.

And following the dictum “what goes up, comes down”, Francis Coppola decided to take it to its extreme. First, he chose an apparently simple but logistically complicated script, based on an interesting but dense book, Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness. He kept his trusted crew and a cast of acquaintances with whom he could feel comfortable. He pulled the right strings to shoot on locations that were sufficiently believable and within budget. So far so good. But over the next three years, this adaptation destined for glory could have killed its director countless times.

When everything that could go wrong went wrong, Francis began to lose his mind as well as his faith in the pages he wrote at night to be shot the next morning, pages that no longer contained dialogue but ideas for improvisations. When the money ran out to the point of asking his former partner George Lucas for it. When Marlon Brando cut 80% of his character’s dialogue at his own risk, just to work less. When half the cast spent the day smoked or hungover. When the sets depended on the storm of the day. When Harvey Keitel didn’t give on-screen what Coppola expected of him, or when Martin Sheen was given the last rites after his not-so-unexpected heart attack. When Francis finally decided to confess to his wife that his film was a disaster for which he felt incapable of even writing a conclusion, a fiasco on which he had mortgaged all his capital and prestige, and after which he could only shoot himself, there was Eleanor’s camera recording it all. This collection of small and big dramas was about a film called Apocalypse Now, but it could perfectly have been called The Agony and the Ecstasy.

Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (Eleanor Coppola, 1991)

Twelve years later, too much had happened. The filmed Vietnam mentioned in the previous paragraph was, against all odds, a winning horse that ended up mythologizing the figure of Francis Coppola. He did the only thing he knew how to do at the time, and that was to invest it all again in an impossible film, shooting an expensive and soporific script: One from the Heart (1982). This false step forced him to accept for the rest of the decade projects to pay off debts. When he regained his freedom, much later, cinema was no longer the driving force that guided his steps. Along the way, he also lost much of his confidence and learned automatisms that helped him not to get too involved in his filming, especially if he wanted to live to a ripe old age. The enfant terrible of the 70s, who reinvented language and the word “risk”, gave way to an old sybarite craftsman.

Sin embargo, Eleanor Coppola había ido juntando sus propios retazos del terrorífico rodaje en Filipinas, incorporando entrevistas de sus implicados y dándole al conjunto una coherencia. Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991), una de las sensaciones de Cannes de ese año era, como su autora, una joya a la espera de ser descubierta, y demostró varias cosas: La pericia de Eleanor a la hora de saber dónde poner su cámara y el olfato para intuir el misticismo que rodeaba a esa mezcla de obra maestra y film maldito. Por primera vez asistíamos a un making off que no se detenía en la anécdota sino que construía un film dentro de otro, recorriéndolo como en un tour turístico, pero deteniéndose en los lugares estrictamente necesarios para explicar las motivaciones que le dieron vida y sobre todo, arrastraron a completarlo. Dieciséis años después, Eleanor intentó el mismo experimento con la Apocalypse Now de su hija Sofia, Maria Antonieta (2007). Pero en este caso, tanto la película como su disección fueron condenadas al ostracismo, una por desmesurada y otra por complaciente.

However, Eleanor Coppola had been piecing together her snippets from the terrifying shoot in the Philippines, incorporating interviews with those involved and giving the whole coherence. Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991), one of the sensations of Cannes that year, was, like its author, a jewel waiting to be discovered, and it demonstrated several things: Eleanor’s expertise in knowing where to place her camera and her nose for the mysticism that surrounded this mixture of masterpiece and cursed film. For the first time, we witnessed a making-of that didn’t stop at the anecdote but built a film within a film, going through it like a tourist tour, but stopping at the places strictly necessary to explain the motivations that gave it life and, above all, dragged us to complete it. Sixteen years later, Eleanor tried the same experiment with her daughter Sofia’s Apocalypse Now, Marie Antoinette (2007). But in this case, both the film and its dissection were ostracised, one for being overblown and the other for being complacent.

While her husband’s career languished in an unexpected and regrettably dispensable comeback (three films between 2007 and 2011, of which only a few lucid moments of Tetro (2009) could be redeemed), Eleanor Coppola gradually found a taste for living outside the inbreeding of the documentary. Her two fiction films, Paris Can Wait (2016), and Love Is Love Is Love (2020), showed more of a taste for the good life (another hallmark of the Coppola clan) than any previous work by any member of her family. Simplicity and pause finally prevailed over that far-flung frenzy, destined to reinvent cinema at the cost of living on a rollercoaster of excess and misery.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!