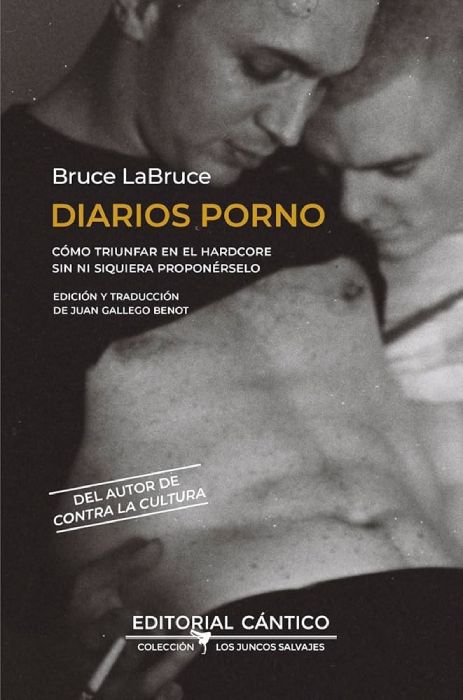

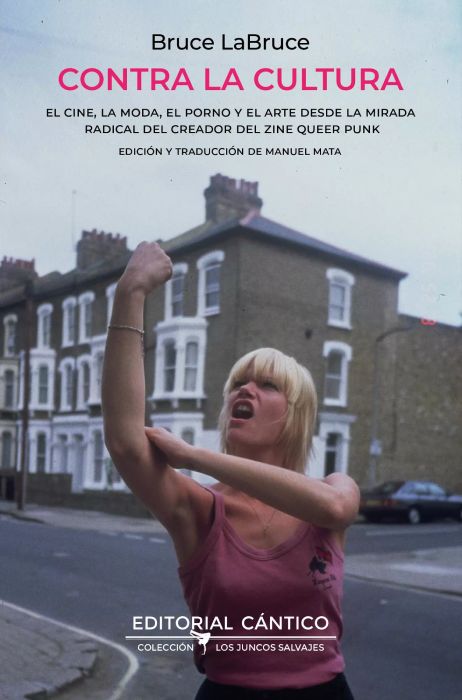

We are in luck. The Almuzara Group’s Cántico publishing house, as part of its “Los juncos salvajes” collection, a name that nods to André Téchiné’s film of the same name, has just published Diarios porno (Porn Diaries) by Canadian filmmaker, photographer, and writer Bruce LaBruce. Considered one of the leading exponents of queercore, his work is part of the MoMA collection in New York and has influenced artists such as Kurt Cobain and Jeff Koons. In 2024, the same publisher released Contra la cultura (Against Culture), a compendium of articles on cinema, fashion, art, and pornography by the same author. These are raw, highly intelligent, and transgressive texts in which LaBruce brings together seemingly contradictory and antagonistic universes to generate new, provocative, politically incorrect paradoxes. He aims social conventions, including those that stem from the aestheticization of culture, especially gay culture, which he accuses of having lost its rebellious character, especially now that the far right is rampant everywhere, something that can be extended to other social movements that emerged in the 1970s and 1980s. For this creator, faithful to his Marxist ideas and deeply iconoclastic, art is about provoking and offending. When nothing is shaken, it is because it has become pure onanism.

I have been following LaBruce for years. I read everything I can get my hands on about him and have watched some of his films on pay-per-view platforms and adult content websites. I don’t attend international festivals, which is the easiest way to follow his work. Fortunately, the internet democratizes and universalizes everything. Even so, I would like to publicly thank Editorial Cántico for bringing this artist’s thinking to Spanish readers for the first time through the two titles mentioned above. Let’s hope that more will follow in the future, including his albums.

Reading LaBruce is like traveling through the underground culture of the last forty years. It is bringing together, on equal terms, the cultured and the popular, the pop and the camp with the most radical punk and the most bizarre gay porn, because these are the weapons he uses to destroy some of the taboos of Western culture.

Considered by some critics to be the philosopher of porn or the punk pornographer, Bruce LaBruce (Southampton, Ontario, 1964), stage name of Justin Stewart, studied at the University of Toronto, where he specialized in film and political science. In the early 1980s, he published his first articles in Cine-Action!, a Marxist-leaning university magazine, and in other Canadian publications such as BLAB and Eve Magazine. In the same decade, he launched his own fanzine, J.D.s, co-edited with G.B. Jones, for which he wrote all kinds of texts and manifestos. J.D.s followed in the footsteps of fagzines in New York, San Francisco, and Paris, which featured contributions from artists and writers such as Pierre & Gilles, Paul Morrissey, Tom of Finland, Divine, Edmund White, and Paul Bowles.

LaBruce’s fanzine quickly found its place in the American counterculture of those years as a queer punk zine that developed a strongly political narrative against the neo-capitalist system. Speculation about the meaning of the initials J.D. in the masthead—J.D. Salinger, James Dean, Juvenile Delinquents, Jack Daniels—helped him connect with younger, more rebellious groups. The success of J.D.s made LaBruce a regular contributor to British, American, and Canadian magazines such as Gay Times, ExClaim, The National Post, Black Book, Dazed and Confused, Toronto Life, and Talkhouse.

Parallel to the publication of the fanzine, he wrote and directed his first Super 8mm short films, in which he mixed the techniques and structures of independent cinema with gay porn and punk, as he had been doing in J.D.s. No Skin off My Ass (1991) is his first feature film, shot in Super 8 and extended to 16mm. Here, Labruce himself plays a hairdresser in love with a skinhead. The film makes immersive use of the sexualization of Nazi iconography and the fetishization of homophobic violence with a clear intention of political denunciation. The intersection of the skinhead, punk, and queer universes would be a constant in his artistic production, allowing him to break down the boundaries that constrain the construction of identities.

LaBruce uses gay porn as a rhetorical device to combat puritanism and hypocrisy. True to one of the characteristics of the gay liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s—initially called the sexual liberation movement—which pushed sex to extreme, experimental, and unconventional limits, the Canadian uses gay porn as a way of raising awareness about society’s repressed sexual impulses. It is a social provocation in the face of the fear of homosexual sex expressed by both the most conservative sectors that condemn it and those of a certain progressiveness that tolerate it as long as it is politically correct. From the radical left, LaBruce confronts this complex, ascendant, and contradictory puritanism, entrenched in a hypersexualized society that is capable of exalting the objectification of men and women while simultaneously generating anti-body and anti-sex movements in the name of new contexts of presumed social progress. The Canadian opposes all this with a merciless visual and textual queercore narrative.

The combination of indie cinema and queercore will open the doors of Hollywood to him. In 1996, he shot Hustler White, co-directed with Rick Castro and starring Tony Ward, Madonna’s model and partner at the time, who would go on to become a regular actor in his films. The film was a hit at the Sundance Film Festival, and Labruce became one of the leading representatives of New Queer Cinema, alongside Castro, Gus van Sant, Todd Haynes, and Gregg Araki.

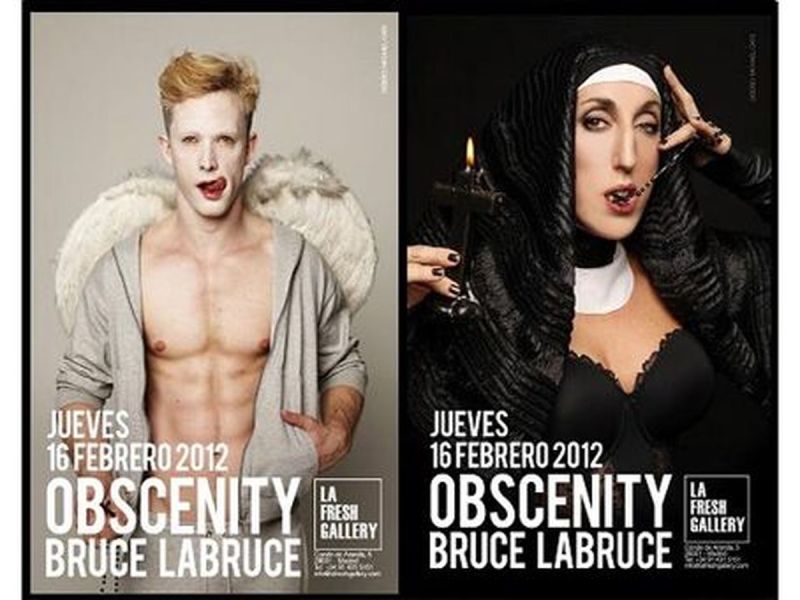

Hustler White also sparked his interest in photography, a language he had studied at the University of Toronto, but which had not caught his attention until then. He worked for Inches and Honcho, American porn magazines for which he did fashion shoots with non-professional skinhead and punk models. His photographic work, a mixture of rage and glamour, was exhibited in galleries around the world, although it was never without controversy. In 2011, he presented 400 Polaroids at the Wrong Weather Gallery in Porto, Portugal. This material was later to be included in Polaroid Rage: Survey 2000–2010, but was held up at Canadian customs for being too risqué. Months later, in February 2012, he created Obscenity for the Madrid gallery La Fresh Gallery, run by the trans artist and activist Topacio Fresh, with Rossy de Palma, Pablo Rivero, Alaska, and Mario Vaquerizo participating as models. The exhibition explores the boundaries between the sacred and the profane through Christian religious iconography. A few days after the opening, the gallery was attacked when a Molotov cocktail was thrown at its façade, but it failed to explode.

The limits of Christian sacredness reappear in the feature films It is Not the Pornographer That is Perverse… (2018) and Saint-Narcisse (2020). The first consists of four interrelated short films. The first two, Diablo in Madrid and Uber Menschen, were filmed in the Spanish capital, while Purple Army Faction and Fleapit were filmed in Berlin. In the film, Spanish gay porn actor Allen King plays a lecherous imp who emerges from a grave and causes confusion among visitors to a Madrid cemetery, with whom he engages in all kinds of sexual practices. An angel, played by American gay porn actor Sean Ford, tries to restore order to the graveyard, and his struggle with the devil ends in a torrid sex session that breaks down the boundaries between the two moral archetypes. In the end, the angel and the devil form an inseparable unity in which neither dominates the other.

Saint-Narcisse, meanwhile, moves away from indie aesthetics to revisit the classic myth of Narcissus. LaBruce turns the story of the young man in love with his own image into an incestuous tale of gay eroticism, polyamory, violence, and redemption. The protagonist accidentally discovers that he has a lesbian mother and a twin brother who is a novice in a mysterious Christian monastery. He has a relationship with his mother’s girlfriend, falls in love with his brother, and frees him from the bondage of the prior of the convent, who considers him to be the reincarnation of Saint Sebastian, a gay icon with whom LaBruce pays homage to Derek Jarman. The result is a delirious indictment of family and religion based on the destruction of the taboo of incest, a mechanism of patriarchal domination on which Western society is based. The Canadian had already attacked the taboos surrounding the family in Gerontophilia (2013), a film with which Saint-Narcisse shares certain aesthetic aspects.

As we have indicated above, one of the most outstanding characteristics of LaBruce’s work is the union of high culture and mass culture in the same field of immanence. The filmmaker has confessed on several occasions to the influence that the exploitation phenomenon of the 1960s and 1970s has had on his cultural development, especially the erotic and pornographic films of those years and B-grade horror films, particularly those of George A. Romero. For LaBruce, these productions, despite their apparent banality, contain a critical discourse against war and political disappointment. Night of the Living Dead fascinated him with zombies.

A character deeply rooted in American popular culture through film, comics, and video games, and exported to all corners of the globe, the zombie is an undead creature with no identity, wandering, flat, and lacking in personality. A misunderstood nihilist who finds no incentives or future in the society in which he lives. These characteristics will make many young people of Generation Z identify with him.

Although the plots of most films and video games propose their extermination so that they can rest in peace and no longer pose a threat to the establishment, zombies display a very interesting polysemy. While they are understood as the dehumanization of the other, of the different, as a precursor to social exclusion and annihilation, they also represent, as certain philosophical currents of the 1990s and 2000s argue, a great metaphor for late capitalist society. The zombie, the dehumanized, the one separated from the real world, is a social prototype that experiences the crisis of the welfare state and the transition from liberal parliamentary democracies to post-democratic financial, technological, and patriotic totalitarianism, with the consequent destruction of the environment. For the time being, modernity seems to have no alternative to this transition.

LaBruce makes interesting use of gorn (gore and porn) in productions such as Otto; or, Up with Dead People (2007) and L.A. Zombie (2010). Considered a cult classic in which the roles are reversed—the threat comes from humans, not zombies—Otto; or, Up with Dead People, presented at the 2008 Berlinale, navigates the stormy waters of softcore and bizarre horror. It tells the surreal story of a zombie with identity issues—he doesn’t eat human flesh—who meets a neo-Gothic film director who proposes shooting a documentary about himself in the context of a zombie revolt against consumer society. With these elements, the film develops an anti-establishment narrative that contains one of the most irreverent phrases in the history of gore: Lazarus was the first zombie; Christ was the second. A quote that, with all due respect, would not be far removed from the holy Christic madness proposed by Erasmus of Rotterdam in his In Praise of Folly in the early 16th century.

Having become a cult film since its shooting, with a controversial premiere at the Locarno Film Festival, L.A. Zombie was banned at the Melbourne Underground Film Festival, where the police searched the director’s Australian home to confiscate the film and prevent its screening because it contained full frontal male nudity and scenes of necrophilia. In this film, LaBruce takes his gorn narrative one step further by introducing a mysterious alien with an enormous, irregular penis, played by French porn actor François Sagat, who emerges from the sea, although it is never clear whether he is an extraterrestrial or a schizophrenic homeless man. This character roams the city of Los Angeles resurrecting the corpses of beggars, drug addicts, drug dealers, and participants in a BDSM orgy by having intercourse with their wounds and showering them with his black semen. If in Otto; or, Up with Dead People the zombies fled from humans, in L.A. Zombie a gay zombie resurrection is proposed as a metaphor for the insurrection of the lower classes and the establishment of a new social order.

Another character who emerges from the water, in this case a naked black man inside a suitcase that appears on the banks of the Thames, a clear reference to the refugee crisis in Europe, is the protagonist of The Visitor (2024), LaBruce’s latest film to date. Presented in the Panorama section of the 74th Berlin International Film Festival, it stars Bishop Black, a well-known African-American actor in ethical porn, a subgenre that seeks equality between men and women. This film is a remake of Teorema (1968) by Pier Paolo Pasolini, a filmmaker much admired by the Canadian. The film tells the story of how this strange visitor arrives at the mansion of a wealthy family, whose members he seduces, leaving them with a vital post-coital void. The film denounces social differences and fascist discourses that veto immigration. The film contains some coprophagic references that evoke Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (Pasolini, 1975).

The films mentioned above can be found on various online platforms, as can Pierrot Lunaire, a title I would like to highlight to conclude this article for several reasons. Firstly, for its extraordinary beauty; secondly, for being an atypical title in LaBruce’s filmography; and thirdly, for being based on the cycle of atonal songs by Arnold Schönberg, one of the composers of the early avant-garde of the 20th century, for whom I have a particular fondness. The film is based on LaBruce’s own theatrical production of this work for the Hebbel am Ufer theater in Berlin in 2011. In the original work, the character of Pierrot is played by a female actress, but LaBruce has it played by a trans actor, turning Schönberg’s piece into a vindication of transsexuality. The film won the 2014 Teddy Award for best LGTBIQ+ film at that year’s Berlinale. All said.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!