The 3rd Bishkek International Film Festival took place on June 11-15, 2025. The festival offered its guests three competitive sections: International (mostly focused on the Asian region), Central Asian (films coming from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan), and KyrgyzBox (local films that have already premiered in cinema and set box office records). Apart from that, a separate section featured a focus on France and Germany, and in the retrospective program, the films of the master of Kyrgyz cinema, Tolomush Okeev, were shown. At the CAF pitch, regional directors presented their projects in development to the international experts.

Kyrgyzstan is a Central Asian country that is not so often in the news: upon looking it up on the web, you will find barely a few clickbait headlines, no major scandals, and almost no global politics involved. Kyrgyz are primarily an agricultural nation with rather minor oil and gas deposits. Representing a peculiar combination of breathtaking landscapes, post-Soviet context, Muslim religion, and authentic local traditions, Kyrgyzstan leads its relatively calm existence compared to many of the neighbouring countries. It is little known to the world, and at first glance, much less bothered by the trends raging outside of its borders. Until recently, it was not much on the international cinematic map either, so when I received an invitation from the Bishkek Film Festival, with no doubts, I said “yes”.

From the very opening ceremony, however, it became clear that in Kyrgyz society, things are in motion. Despite the presence of quite a few important international names, including British actor Dominic West, Italian actor and director Michele Placido, and Russian director Sergei Bodrov, the highlight of the Sky Carpet (Bishkek’s equivalent of the traditional red carpet) was an appearance of the local blogger Zhanara Osmonalieva wearing a revealing transparent black dress. The cameramen inadvertently savoured the moments of her walk, with it being streamed on the big screen in a national philharmonic theatre. That very night, social media erupted with heated discussion, with one side attacking Osmonalieva for vulgar behaviour and another praising the blogger for a brave provocation that challenged constricting societal norms. The discussion continued days after the festival as the blogger was arrested for “petty public disorder”. As editor-in-chief of the exclusive.kg Semetey Amanbekov commented on his social media, I see a problem – the inability of society to tolerate people who do not fit into the picture… In our society, beating, humiliating, raping are still a “personal family matter”, “everyday life”, “education”. It seems that we are ready to tolerate violence – but not freedom of speech.

Though it feels rather disheartening that this incident was clearly of a bigger interest to the public than many of the films screened over the next few days, it was but a portent of deeper layers of the burning social issues of modern Central Asian countries to be unveiled through the regional competition program.

The film industry in Central Asia is still in its early development stage, perhaps with the exception of Kazakhstan which takes up the leading cinematic role in the region. It was a Kazakh film Abel by Elzat Eskendir that opened the screenings. Abel tells a story of political shifts in the country and people being but helpless cogs in this greater and merciless machine. I happened to watch this film before at the Goteborg Film Festival; prior to that, it premiered in Busan, and in July, European audiences will get the chance to see it again, this time in Munich. Such international recognition seems almost unthinkable for the rest of the films in the competitive section of the Bishkek Film Festival.

As much as I always try to respect jury duty and separate personal cinematic preferences from the analytical approach of a film critic, there was one film in the selection that I couldn’t bear until the end, Open Eyes by Gulnara Ivanova from Uzbekistan. That’s what everyone coming to the festivals in developing regions should be ready for: sometimes, you have to suffer through not-up-to-the-standard productions to be able to discover a few gems.

One of the films that was of particular interest to me came from Turkmenistan, a country infamous for suppressing freedom of speech as well as violation of human rights. There are a lot of rumours spreading around the web about ridiculous restrictions imposed on citizens; for one, it is discussed that women in Turkmenistan are not allowed to have eyelash extensions and hair dyeing or sit in the front seat of a car. It is difficult to verify as this country is also one of the least visited in the world, with one of the strictest visa policies. The film presented in the competition was titled Kitap (The Book) and told us a story of the book by Magtymguly, a national philosopher and poet. Produced by Turkmenfilm, it was a precious example of so-called non-conflict dramaturgy, popular in the Soviet Union genre.

The theory of non-conflict is a term coined by Soviet criticism of the 1950s, referring to the literature of the conflict of “good against the best”, in contrast to the classical conflict of “good against bad”. Following this theory, the film narrates the story of the linguist who discovers a unique Magtymguly book and wants to disseminate it among all people. Even though the film itself couldn’t spark much discussion, the Q&A with the director Hekim Alavov was rather eloquent. He barely answered any of the questions, and a strong suspicion was raised that he is very cautious about each and every word he uttered. Replying to a notion about Turkmenistan being a closed country, he assured the audience that it was not so, and anyone was welcome to come, including those who want to make films.

Four other films (two from Kyrgyzstan and two from Uzbekistan) explored the topic of the position of women in Central Asian society, disclosing very disturbing tendencies that are often silenced on a public level. While Uzbek films (In Pursuit of Spring by Ayub Shahobiddinov and In Pursuit of Truth by Manzarali Sherali) were delivered at a considerate, moderate pace and followed somewhat similar narratives about the women in the village that must abide by the strict societal norms, both Kyrgyz films used genre approach, were utterly expressive and provoked a lot of emotions in the audience.

Immediately after the screening, the Kyrgyz film Burning by Radik Eshimov was given the title of “Kyrgyz Rashomon”. Three stories unfold in front of our eyes, showing three different perspectives. Starting as a horror, its dynamic narrative gradually transforms into a poignant social drama, revealing the oppressed position of a woman who suffers from domestic abuse. The boldness with which the horror genre was applied to such a delicate topic was well-justified: authors deliberately resorted to entertaining tools to attract the audience, and then, under the pretext of entertainment, dropped an ethical bomb, asking a question: would each of us step in, if we saw the injustice next door? Or is domestic abuse still a “personal family matter”?

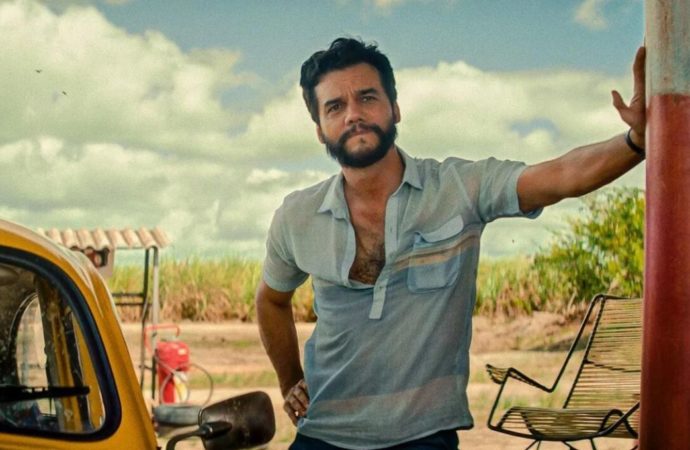

Even more provocative was the film titled Mercy by Sapar Saynazarov. This thriller fearlessly tackled the topic of victim shaming, telling us a story of a young girl raped by a rich man. Saynazarov’s directing style could easily beat any Hollywood blockbuster: from the very first to the last frame, the viewer is exposed to non-stop action with the speed and volume stunning in his debut work. Though perhaps such a film felt like a rather unconventional choice for a festival, the feedback it provoked in the audience was truly impressive. Many women shared heartbreaking stories of a similar experience, and the time dedicated to Q&A was not enough to even approach the essence of the issue, let alone find the answers.

Contrasting to its competitors, one of the strongest impressions from the program was made by a Kazakh fiction film executed in documentary stylistic, Joqtau by Aruan Arantay. Distinguished as a Best Director, Arantay explores his native land through the camera, trying to express the grief that has settled in him since the demise of his grandfather. Tackling complex topics of identity and belonging, as well as processing the departure of a dear person, this film stays truly sensitive and gentle to every character and every detail that constitutes the surroundings. It makes you desire to travel to Kazakhstan, to experience its vastness and beauty, to immerse yourself in its culture. This film is a must-see for everyone who appreciates great camera work.

Joqtau had its world premiere in Locarno and has already travelled around festivals. It could have well been nominated for the best film of the Central Asian competition in Bishkek if it were not for the last contestant, the Kyrgyz movie Mergen by debut director Chingiz Narynov.

Produced by Kyrgyzfilm, Mergen sparked visible interest among the locals, which even resulted in conflicts before the screening, as space was simply not enough to accommodate everyone who wished to attend the world premiere of the film. With people sitting on the stairs and standing in the aisle, the screening has started. We were transferred to a remote mining city in the Kyrgyz mountains, a city that declined together with the production of gold. One by one, we were introduced to characters inhabiting the city and hidden conflicts that invisibly tied them together. It could have been just a masterful social drama if it were not for the extrasensory abilities that the leading character, a young policeman, possessed. In his visions, he is dimly foreseeing advancing darkness, a hint of the tragedy that is about to happen, and he is desperately trying to prevent it. A diverse array of supporting characters deserves separate recognition, with one of them bearing an uncanny resemblance to Chief Bromden from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Balancing between the corrupted reality and omnipotent mysticism, Narynov shows Kyrgyzstan not only through people but also through nature and folklore, creating a complex understanding of modern Kyrgyz society, as well as its historical perspectives.

Mergen triumphantly won the Best Film award together with the prestigious FIPRESCI–Film Critics’ Prize. This film became that very gem worth coming to Kyrgyzstan for, and it will gain broader recognition at the festival circuit worldwide.

Bishkek festival’s programming left mixed impressions. Inconsistent at times, it managed to engage the audience and present a few truly strong titles. At the same time, it had to make compromises, as sometimes there was no choice: in countries like Turkmenistan, there are barely a few films produced annually. Governments have a strong say in the cinema industry of Central Asia, and filmmakers have to pave their way to the screen in a rather difficult political atmosphere. There are many obstacles, but also a lot of potential in this region, and it is privileged with a sense of novelty and a variety of unexplored topics, which matter not only on screen but also in real life, that they can influence and transform.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!