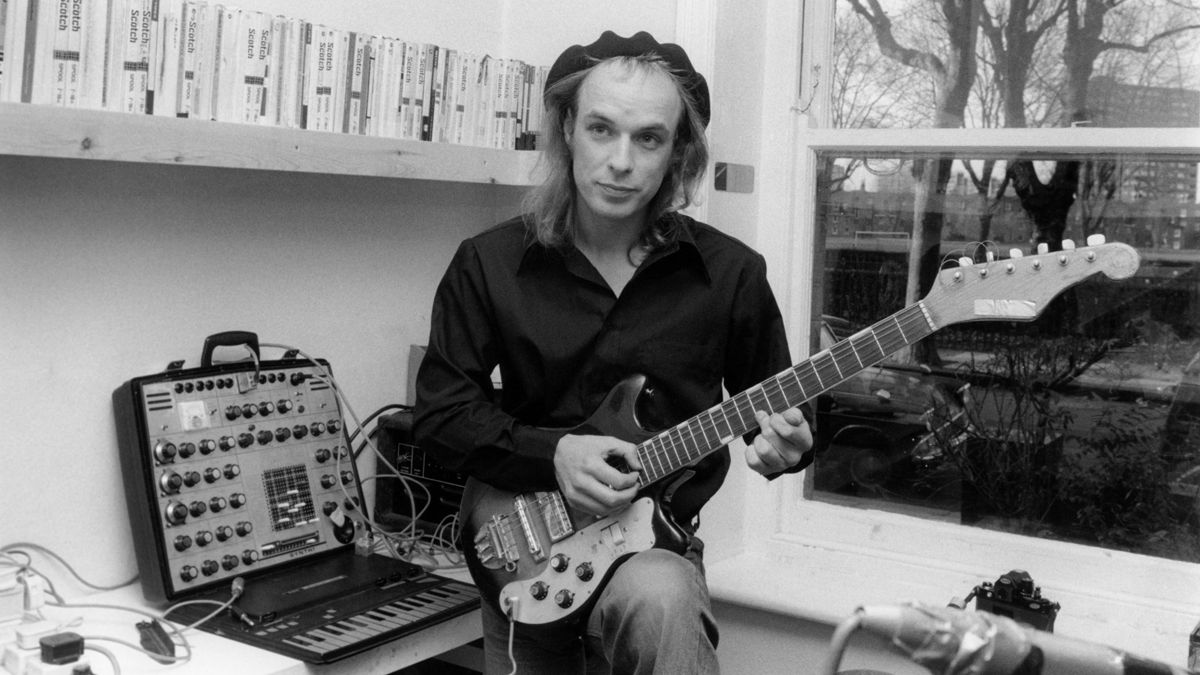

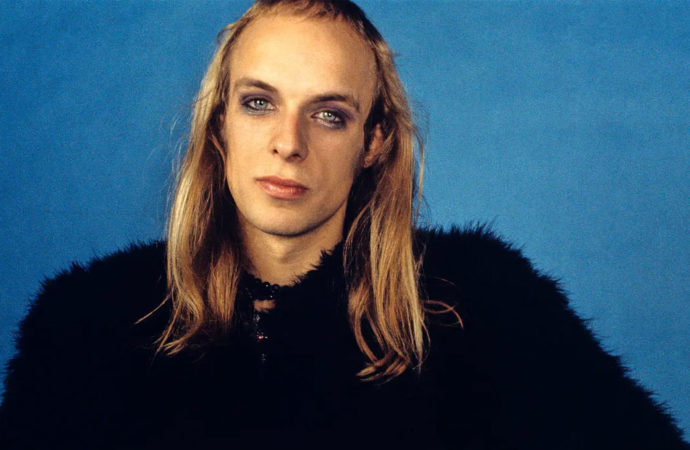

Brian Eno, who in the early days called himself just Eno, had the look you should expect from an experimental musician. No long-haired, sweaty geeks around a table scribbling massive works. Our protagonist was resplendent with the androgyny of glam rock where he had grown up, with stunning blond hair and flaming suits.

Even as a young boy he cultivated his legendary come-from-behind attitude, with experimental attempts such as hitting pianos with tennis balls. After playing on the first two albums of the glam/art rock band Roxy Music, he split up due to differences with their leader and began a solo career that at first didn’t have the same momentum… but he was content with his new range, surprised that anyone would listen to his ravings after all.

His way of generating music was always peculiar. We should not take his lyrics too much into account, as he himself acknowledged that they were born from humming. Another method consisted of dancing to get the group to follow his rhythm. These unorthodox procedures would take shape in his Oblique Strategies: letters with gnomic phrases that seek to awaken creativity in periods of blockage.

The title of his first solo effort, Here Come the Warm Jets (1974), evokes the urge to piss. The style is avant-garde pop, but pop. Musically, he took the basic song and liquefied it, retexturised it, assigned new sounds: a sort of pop-art, sometimes saturated and opaque (as in “Here Come the Warm Jets” or the glam “Needles in the Camel’s Eye”), sometimes bubbly (“Blank Frank”). Despite the presence of “real” instruments, everything is rather synthesised, which generates rather cold sounds, like those of “Baby’s on Fire”, with a long solo by friend Robert Fripp. When he tries to be a little more welcoming, as in “Cindy Tells Me” or the paradisiacal “On Some Faraway Beach”, his human warmth is that of the sign of a holiday resort in the desert.

Almost simultaneously, Eno became a producer. Over the years he would gain a reputation as the producer of the “experimental album” of each artist, who were sometimes experimental beforehand, but often looked to Eno as the fastest way to become so. The list is extensive: U2, David Bowie, Talking Heads, Sinéad O’Connor, Ultravox, Devo, Coldplay or Penguin Cafe Orchestra, to name but a few. After releasing his solo debut, our restless protagonist took a chance with John Cale and the Portsmouth Sinfonia, an orchestra whose only requirement was that the musicians knew nothing about the instrument they were going to play in it, and in which Eno wanted to prove that he was not a clarinettist.

Before the end of 1974 a second album was released: Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), inspired by a series of Chinese revolutionary postcards and their Oblique Strategies. The music was not as explosive as on the previous album; the highlight is perhaps the song of the same name. Its successor, Another Green World, waited until September 1975. Again, it all started with a creative block, in which Eno had to modify the timbre of his instruments and pull out random chords. What came out must have surprised even him: there’s little of the glam panache left here, and what’s left is a step away from the abyss. Only five songs with vocals survive: the rest are instrumentals, each with a different personality, often blatantly simple, but effective thanks to a refined craftsmanship. Minimalist and emotive like “The Big Ship” or “Becalmed”, sombre or tragic like “Spirits Drifting” or “Sombre Reptiles”, all maintain a pensive calm. “Zawinul/Lava” and “Little Fishes” are difficult to apprehend in terms of melodic phrasing, a step away from Eno’s music to come.

Among those that do have a human voice are “Golden Hours” and “St. Elmo’s Fire”, both with Robert Fripp on guitar. It is not difficult to imagine the influence that some of the textures (“Sky Saw”) will exert on new wave and synth-pop, and the instrumentals are proof that Eno felt increasingly comfortable in the introverted skin of a musical theorist and experimenter by profession with which he has gone down in history.

Just two months later, he coined the concept that defined what he had been unknowingly searching for all this time. It is the so-called ambient, of which he is considered the founder together with Basil Kirchin. A music that makes sense both in the darkness of headphones and in an extra-musical context, fused with space. It flows in slight and often repetitive variations, floating resonances that can exhaust the attentive ear and escape the distracted ear. The idea came partly from Erik Satie‘s category of “furniture music”, decorative music that is there without attracting attention, and partly from the experience of listening to an almost inaudible harp recording, during an accidental convalescence that prevented him from getting up to turn up the volume. Mythologically, a scene akin to the serendipitous discovery of full abstraction by Kandinsky, who realised that a certain painting looked better upside down than right side up.

In reality —despite his marketing to the contrary— this was not the first time that Eno had dared to take such an approach. Already in 1973 he had created a proto-ambient album with his inseparable Robert Fripp, called (No Pussyfooting), where Fripp’s expert guitar was treated with delay techniques developed between them, and this even before Eno started his solo career. But it’s true that it wasn’t commercially successful, it was denser and less transparent, not all the credit was his, and besides, when he conceived Discreet Music he came with the concept freshly baked under his arm. So let’s let it go.

Discreet Music is divided between the title theme, a thirty-minute celestial reverb, and three free variations on Johann Pachelbel‘s more melodic Canon in D major. In some of these it is impossible to recognise the original, partly because they are ‘generative music’, which aims to reduce the artist’s personal intervention by creating systems that evolve at their own pace. Generally, different instructions were given to each musician (with some kind of symmetry) and the overlapping patterns were recorded or mixed.

Eno would return to make an album of old-fashioned material two years later, Before and After Science (1977), whose title announced that the time for fun was over. It contains perhaps the best set of melodies of his career, a worthy swan song just before he plunged into the new ambient genre, with titles as significant as Music for Airports, Music for Films or Music for Installations, and to combine them with his facet as a producer always attentive to anything that smelled of novelty.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!