In what is the eleventh season and the first in two years, Dokuarts has returned with a program of 30 documentary films titled Beyond Format. In its regular Berlin location at the Cinema of the German History Museum on the central Unter den Linden, this year’s season program focuses on unformatted artistic documentary films that have eluded any convenient sub-generic categorization. Such independent documentaries were a regular feature of the German TV channels such as ZDF in the 1970s and 80s, but have since virtually disappeared from today’s German television programs in a commercial-only age that first took shape in new regulations from the 1990s, even on the Franco-German Arte channel. This is often the case in other countries where the paradox of more TV channels and potential for broadcast in the digital age has in fact only been subservient to commercial and mainstream demands. As a result, much of these innovative new works have been relegated in profile to ever decreasing art cinemas, niche film festivals and the internet.

Dokuarts 11 – Beyond Format presents current documentary film work from all over the globe with unconventional multi-medium artist portraits, essay films, and personal panoramic observations of the world. Yet, despite these renowned filmmakers and their artist subjects, and the documentation of working processes being very popular internationally, only a few of these films are seen beyond their premieres at film festivals and special events. Dokuarts at least tries to redress this weighting a little by showcasing such films and their significance in the current artistic and political climate. In this season, all films are shown in Berlin for the first time, most a German premier, and with most filmmakers present to introduce their films and conduct a Q&A afterwards which is open to the audience.

The season opened in remarkable fashion with the first Berlin screening of the documentary Bergman – A Year in a Life which looks at a single year, 1957, a year which was somewhat pivotal in the long career of the legendary Swedish film and theatre director Ingmar Bergman.

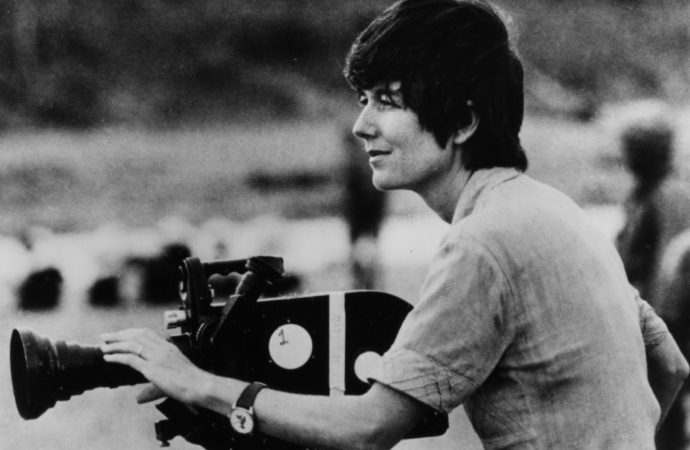

1957 was the year Bergman released two of his most acclaimed features (The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries), made a TV film and directed four plays for theatre (including Peer Gynt). In what is in 2018 the 100th anniversary of Bergman’s birth, Swedish filmmaker Jane Magnusson has amassed a wealth of rich archive footage and miraculous finds, alongside clips from his career and contemporary interviews, to create a new angle on the charming and temperamental genius that many consider the best film director ever and certainly the most famous export of Swedish cinema. The result is a fresh and exhilarating new take on the master and also a digestible introduction for neophytes.

Director Jane Magnusson couldn’t be present to introduce her film and conduct a Q&A but a worthy stand-in was Henrik von Sydow, the son of Max von Sydow (who starred famously as the iconic knight who plays chess with Death in The Seventh Seal), and also (and somewhat appropriately) the story editor of the documentary. He is chiefly known for his involvement as assistant director on Gorky Park (Michael Apted, 1983), The Women on the Roof (Carl-Gustav Nykvist, 1989) and more recently as director for the TV movie Gunnel Lindblom: Out of the Silence (Sweden, 2018) in which he also worked in collaboration with Jane Magnusson (co-writing) for the biography of one of Bergman’s regular “Stars” (a popular depiction of Bergman’s returning actresses in his oeuvre which also included Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson).

During the Q&A with Henrik von Sydow afterwards, conducted by the Austrian film journalist and biographer Bert Rebhandl, he talked of the editing process of the film, how exciting it was to revisit 1957, especially regards his father, and not least the discovery of some rare Bergman photographs from his films, most discovered by chance in various archives in the South of Sweden, and previously unseen on film. He also compared interviewing a Swedish person with three people in the room (including himself and the director) to the likes of Barbara Streisand where there were 14 people in the room. Finally, he noted how young test audiences were amazed how much Bergman could achieve in just one year.

A Year in a Life © Svensk Filmindustri

The first full day of this year’s festival was dominated by the International Symposium ‘Beyond Format’, which took place in cooperation with the European Documentary Network. Guest speakers and presentations discussed various but inter-related topics which looked at the historical, present and continuing formatting of media and culture as well as the interrelations between conditions of production, aesthetics, and politics in the context of films on art as well as the future prospects for the currently marginalized unformatted documentary film. Starting with a welcome address by Andreas Lewin, Artistic Director of Dokuarts, the next four hours featured an opening keynote presentation (in German) on ‘The External Reality: Notes/Thoughts on the Relationship between Photography and Documentary Film’ by Bernd Stiegler, Professor of German Literature and Media History at the University of Konstanz. The rest of the afternoon was a series of case studies and lectures followed finally by a panel discussion. In her presentation on ‘Format, Form and Power in German Public Television’, Sabine Rollberg, Academy of Media Arts Cologne, talked about the steady and inexorable decline of content on major television channels in Germany since the 1990s and the reasons for this, paying particular reference to the business politics of ZDF and Arte TV Channels, lamenting the loss of high quality documentary output on TV in the 1970s and 1980s.

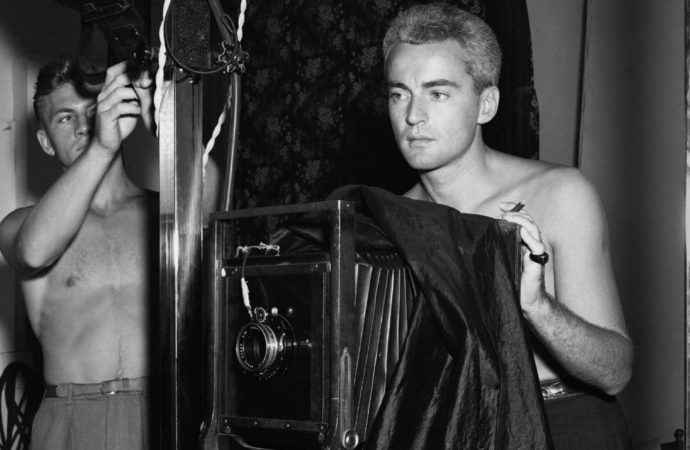

Filmworker © Jacob Rosenberg

The documentary director Tony Zierra talked about ‘Filmmaker’s Rights – A Kubrick Case Study’ in relation to the clips he was allowed to use for his documentary Filmworker (2017) on Stanley Kubrick’s loyal actor-turned-assistant Leon Vitali. For 25 years, since acting in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975), Vitali was the loyal assistant to Kubrick, practically giving up his acting career and personal life in the process to work tirelessly for the legendary director. He talked about how restricted he was from using photographs and footage back in 1989 when he started making documentaries. He met Leon Vitali in 1999 when he was making a documentary on what turned out to be Kubrick’s last film Eyes Wide Shut. What struck the director was Vitali’s story so he decided to do the documentary on him instead. Though restrictions were still in place to use photos and footage because Kubrick (as opposed to, say, Gerorge Bush) is not considered a public figure, he had limited access to stills from Kubrick’s films but also if you can make a case as to why you want to use a clip, you are sometimes given freedom to do so. When his documentary Filmworker played at Cannes, he was bombarded with legal threats but he knew that when he got the film into the press then he knew he could escape legal action.

Stanley Kubrick. Courtesy of Leon Vitali

Paul Pauwels, the Director for the European Documentary Network, and based in Copenhagen, talked about ‘Perspectives for Documentaries Beyond Format’ with the recounting of his experiences over the last 30 years in various production roles in the documentary film industry as a producer, commissioning editor for a public broadcaster which he considered tthe wo most horrible years of my life, and for the past six years has been defending the interests of documentary filmmakers. He believes good communication and mutual understanding helps create openness for new ideas and laments the fact that programmers (particularly on TV Channels) these days greatly underestimate the intelligence of the audience.

For her presentation The Private is still Political! Barbara Visser, an artist and filmmaker from Amsterdam, talked in relation to her film in the program, The End of Fear. In 1969, the Stedeljik Museum in Amsterdam purchased Barnett Newman’s large canvas painting Who’s fraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III that was destroyed in 1986 by a visitor to the museum, himself a painter. Its restoration caused legal and authenticity issues, while Visser reprocessed the double slaying by commissioning a young artist to reconstruct the painting, causing problems of representation itself. She believes that documentaries are deliberate and they are subjective so calls them fake news in the best sense of the word.

Finally, there was a panel discussion with the speakers from the conference that was moderated by Jörg Taszman, the German film critic of Deutschland Radio Kultur, Die Welt, and epd Film.

One of the subjects that came under the spotlight was funding for documentary films. This has also become more difficult but, according to Paul Pauwels, at the same time the increasing number of film festivals also includes a festival’s own funding to get documentaries produced. In response to this, Tony Zierra said his experience was that it was the older established directors that were getting the funding and then distribution, and that younger people were getting nothing, so the wider scale of funding is unbalanced.

Afterwards, there was a live essay and screening of the new digital restoration of Bruce Connor’s landmark film Crossroads (1976) under the title ‘Crossroads and The Exploding Digital Inevitable’, a nod to Andy Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable multi-media events. In its German premiere, the restoration and performance is the work of Ross Lipman, Filmmaker, Restorationist and Film Scholar in Los Angeles. Originally made for the intention of being released for the 200 year anniversary of American independence, Bruce Conner’s meditative montage from original footage of the first nuclear weapon testing at Bikini Atoll in the Pacific Ocean in 1946, in a newly restored digital version, the ‘live-essay’ was a two part performance happening. With the use of interviews and archive material, Lipman has meticulously but sensitively updated the production of the film, which is therefore no less powerful and shocking today as it must have been in 1976.

During the course of 17 days, other highlights of Dokuarts, 11 weights towards visual art and photography and but also strongly represents music and film as well as architecture and poetry. The season also takes place simultaneously with the European Month of Photography (28 September-31 October) so six films featured the art of photography over the course of a single weekend, from October 12-14, with European and German premieres and the presence of photographers such as Daniel Schwartz and Harry Gruyaert and their films with Beyond the Obvious–Daniel Schwartz: Photographer and Harry Gruyaert – Photographer respectively. The former looks at the dedicated work of Daniel Schwartz, who is not only a photographer but also a writer and an artist.

Director Vadim Jendreyko travelled four continents to film his Swiss subject in what becomes an autobiography of Schwartz’s relentless photo research on glacier melt and climate change. Gerrit Messiaen’s portrait of Magnum (international photographic cooperative) photographer Harry Gruyaert gives an extensive insight into his life and works that also serves as a tireless journey across time periods, cultures, and continents. Meanwhile, in Black Mother, Khalik Allah looks at African-Americans on the fringes of society and turns to his Jamaican roots to draw attention to stereotypes that dominates so many social reportages. In Raghu Rai–An Unframed Portrait, director Avani Rai shows beautifully how her father’s pictures have documented India far beyond memory and the collective imagination in a portrait of another Magnum photographer who was lauded not least by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Garry Winogrand: All Things are Photographable is a portrait of an American photographer now revered as a 20th century photo-poet. Though highly regarded as a street photographer he was also accused of sexism in his work so filmmaker Sasha Waters Freyer takes a feminist perspective for her documentary on the influential but at times controversial photographer. Joel-Peter and Jerome Witkin are identical twins and respectively provocative, often grotesque photo photographer versus socio-political figurative painter. For Witkin & Witkin director Trisha Ziff reunites them on the big screen to illustrate their identities and differences.

The ‘Dokuarts – Beyond Format’ season continues at the Cinema of the German History Museum in Berlin until 21st October.

No one has posted any comments yet. Be the first person!